In India, dance is considered to be divine in origin. The gods and goddesses not only take great delight in dance, drama and mime but many are great dancers themselves.

(Anonymous)

Introduction

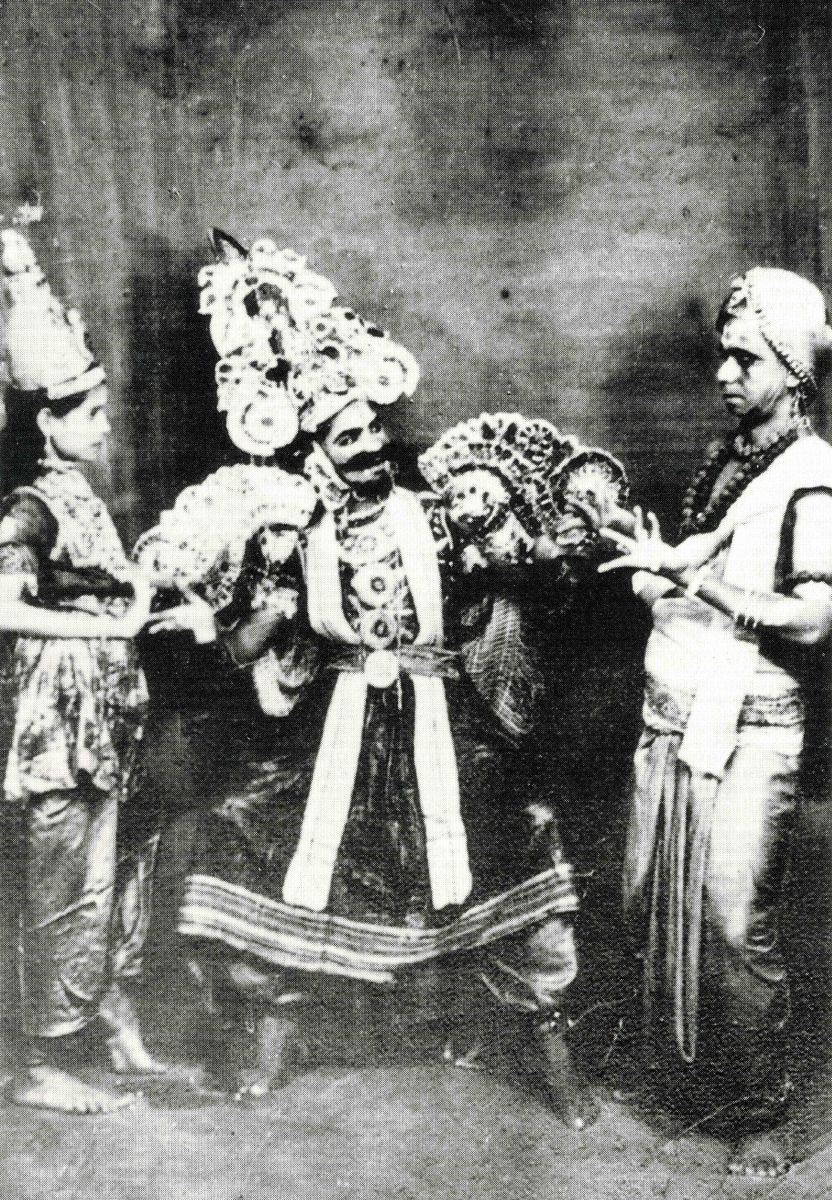

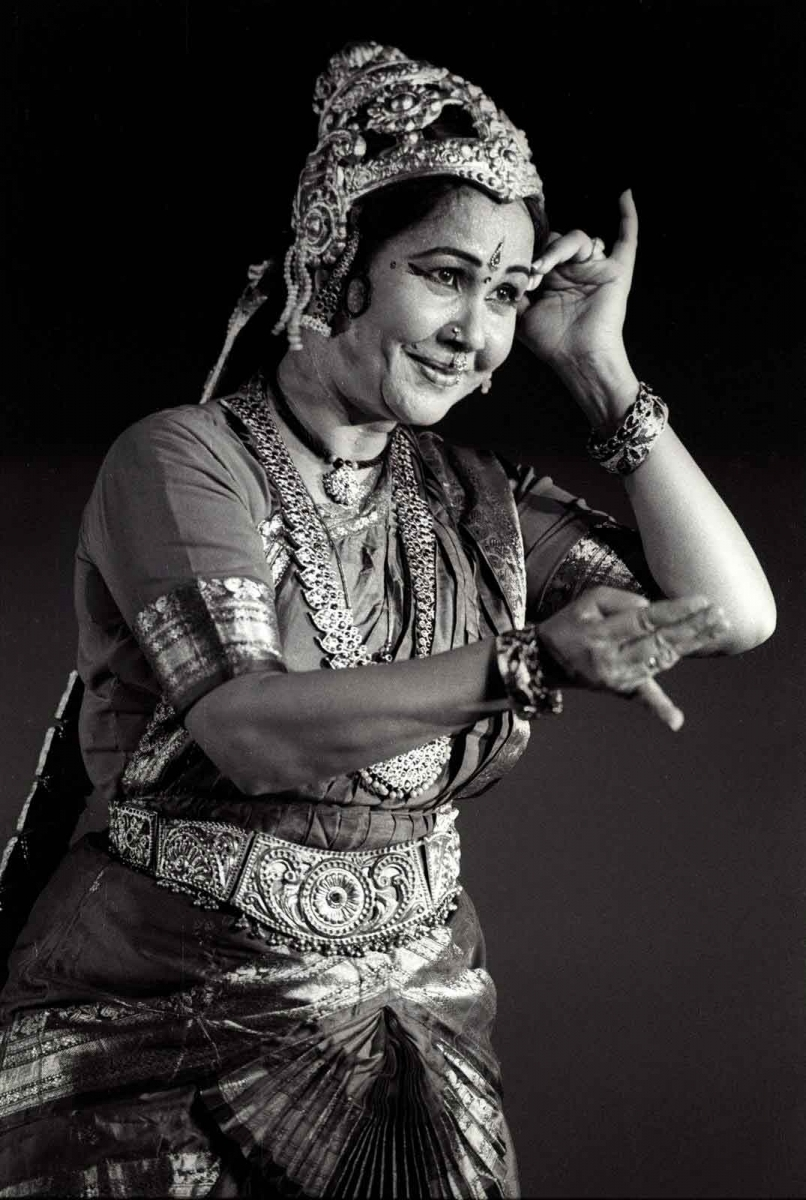

The dance traditions of Andhra are divided into two distinct styles—the Nattuva Mela and the Natya Mela. Nattuva Mela (Fig. 1) is a solo dance performed by women, and the nattuvangam (cymbals played for rhythmic support) is generally played by men. The repertoire of this style of dance consists of both Sringara (erotic) and Bhakti (devotional) items. This is the form of dance that both the temple dancers and the court dancers practised and performed with gods or kings as the hero of the theme of their dances, as the case may be. The second style of dance, Natya Mela (Fig. 2), is generally performed by both men and women. The repertoire consists of dance dramas with themes, not necessarily religious, to entertain the audience and also to update the community with the policies of the provincial kings, known as samantha. This latter form of dance is believed to be the forerunner of present-day Kuchipudi dance.

Kuchipudi is a male-oriented dance-drama tradition that acquired its name from the village it originated from. Both the styles, Nattuva Mela and Natya Mela, suffered due to exploitation and feudalistic abuse. It is at this time that the great saint Siddhendra Yogi appeared in the scene and gave the Kuchipudi dance form a new definition and direction. Siddhendra Yogi refined and redefined Kuchipudi as it is known today.

It is believed that he hailed from Kuchipudi, came to Udupi and became a follower of Madhvacharya. He later migrated to Andhra Pradesh’s Krishna district. Siddhendra Yogi first developed a unique and particular style based on the Natyashastra, Bharatarnava and Nandikeshwara's Abhinaya Darpana. However, Siddhendra Yogi confined the practice of the dance form to only male Brahmins, by training them, and thereby giving the dance the sanctity of the fifth Veda. As such, even female roles were played by men. Siddhendra Yogi is also credited with the composition of many kalapams (dance dramas) and one of them is the famous Bhama Kalapam (story of Sathyabhama, Krishna’s wife).

The male Kuchipudi artists are known as ‘Bhagavatulu’. About five hundred Brahmin families belonging to Kuchipudi village have been following this tradition for over five hundred years. At least two historical pieces of evidence speak for the antiquity of this dance form—the Machupalli Kaifat of 1502 and the historical records showing that the Kuchipudi village was given as an agraharam (grant of land) to the Brahmin artists of the village by the ruler Abul Hasan Kutub Thani Shah in 1675.

A Historical Overview of the Form of Kuchipudi and its Emergence

When we go back in time during the reign of Sri Krishnadevaraya of Vijayanagara, we see that the Tamils and the Kannadigas came together with the Telugus under the patronage of this king. Further, he conquered Tanjore and Madurai and appointed Telugu nayakas as rulers of those areas. These nayakas patronised fine arts and encouraged Telugu poets, musicians and dancers who had migrated to Madurai and Tanjore from the Telugu country.

At the end of the fifteenth century, we find a reference to a Yakshagana performance in Someshwarasatakam by an unknown poet. In one of the verses, the poet says that he witnessed a grand performance of Sathyabhama’s character all night through dance and drama.

During this period, troupes known as melas performed Yakshaganas, travelling from Andhra to Tanjore. The Tanjore kings encouraged Yakshagana performances to such an extent that the rulers also took part in it personally. It was so popular that, during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Telugu Yakshaganas were being performed in the temples of Tanjore by Bhagavata Melas.

Raghunatha Nayaka and his son Vijayaraghava Nayaka of Tanjore, during the seventeenth century, wrote several Yakshaganas in Telugu. The Maratha rulers of Tanjore, who succeeded the Telugu Nayakas, also learnt Telugu and wrote Yakshaganas in Telugu. This points towards the popularity of Telugu Yakshagana in Tanjore since the sixteenth century. It attracted neighbouring melas from Karnataka who had already come in contact with the Vijayanagara Empire. They too began to write Yakshaganas from the seventeenth century onwards. In the Telugu Yakshagana Mannaradasa Vilasa, written by the poetess Rangajamma in the court of Vijayaraghava Nayaka, different characters speaking Tamil, Kannada and Malayalam were introduced. These incidents prove that other South Indian languages imitated the Telugu Yakshagana.

Till the fifteenth century, non-Brahmin women were presenting Yakshagana performances as stated in the literary work Kridabhiramam, written in Telugu. From the beginning of the sixteenth century, Kuchipudi Brahmins took up the profession in troupes and toured all over South India presenting Yakshagana performances. This is one more version of the history of the emergence of this dance form. In these troupes, men took up the roles of women. It may also be said that during this period, Yakshagana performances reached its zenith through the Kuchipudi Brahmins. There is recorded evidence to show that, during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Kuchipudi Bhagavatars or actors visited all parts of South India and received accolades for their performances.

At Tanjore, during the rule of Raghunatha Nayaka and Vijayaraghava Nayaka, the Kuchipudi actors were encouraged and honoured as well. Some families of Kuchipudi troupes settled at Tanjore. Melattur Venkataramana Sastri, who wrote several Telugu Yakshaganas for the Tanjore temples, belonged to one of these Kuchipudi troupes. There is also ample proof to show that the Kuchipudi troupes went to Malabar for performances.

All these facts can lead one to notice that the Andhras were the pioneers in the field of Yakshagana, and it might not be wrong to state that with their influence, Yakshagana developed in Tamil and Kannada areas as well. Thus, Yakshaganas occupy a unique place in our literature and also serve to be a strong basis for the growth of Kuchipudi as a dance form performed today.

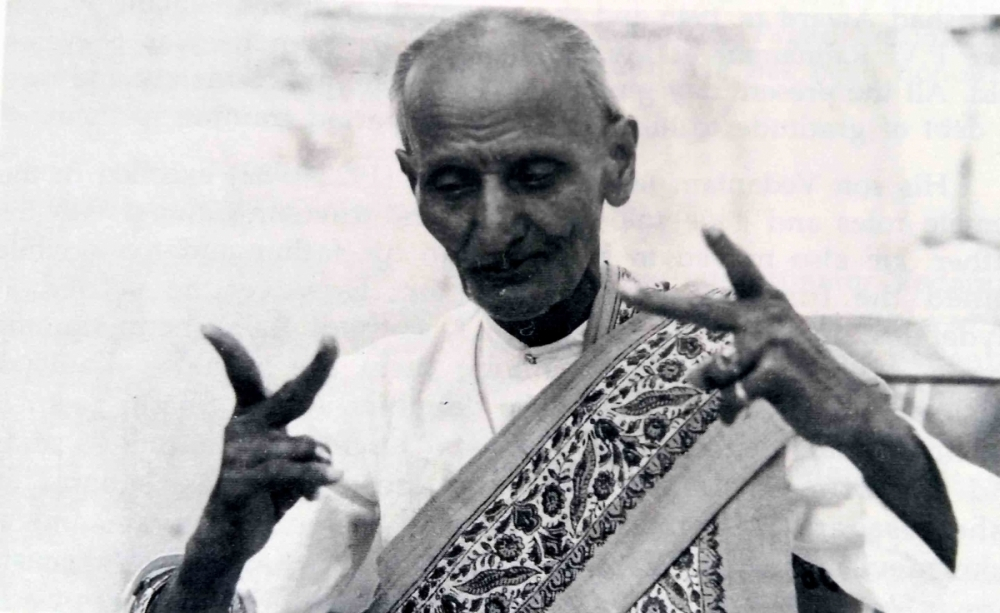

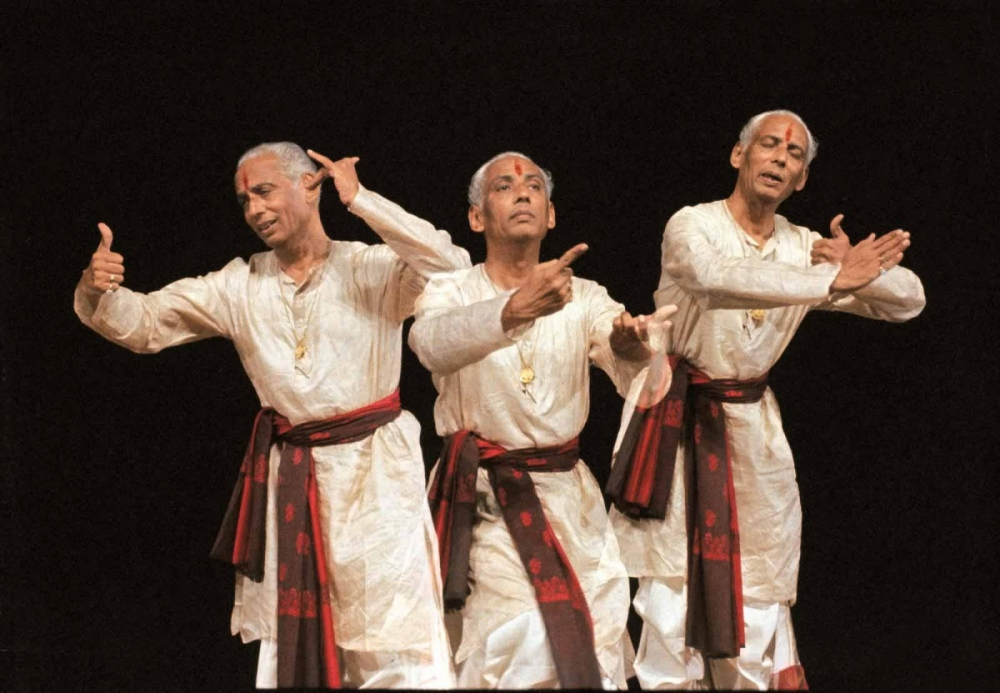

Great gurus like Vedantam Lakshminarayana (Fig. 3), Chinta Krishna Murthy, Tadepalli Perayya enriched the repertoire and also brought women into this form of dance. Names such as Dr Vempatti Chinna Satyam (Fig. 4), C.R Acharyulu (Fig. 5) and Dr Korada Narasimha Rao contributed many more dance dramas and choreographed several solo dance compositions, widening the scope and genre of Kuchipudi.

The development and transformation of this dance form have come a full circle, from the days when men played female roles, to this day when women are playing male roles.

Kuchipudi Yakshagana

There is overlap between gendered performance practices as well as genres such as Yakshagana, Bhagavata Mela, Kalapam, solo repertoire and Pagati Vesham (dancers wearing various god/goddess costumes and enacting their characters)—practices and genres that are treated as mutually exclusive in mythopoetic narratives about Kuchipudi. The earliest documented performance traditions practised by the men of Kuchipudi village fall under the categories of Kalapam and Vesham. Originally a literary tradition, Kalapam did not emerge as an established performance genre until the late nineteenth century. Around this time, Kalapam texts became visible through performances by a variety of groups, both female and male. These texts fall into two categories: those that are based on narratives about a character known as Satyabhama, called Bhama Kalapam, and those that are based on a conversation between a Brahmin and a Gollabhama (milkmaid), called Golla Kalapam.

In the Indian art scene today, Yakshaganas are found in the Telugu, Tamil and Kannada languages of South India—but the art would have had its origin in only one of these languages, and the others may have drawn on a great influence from that tradition.

Dr V. Raghavan, in his essay on ‘Yakshagana’ comments, ‘To the vast indigenous theatre of India, the contribution of South Canara is the Yakshagana.’[1] He repeats this at the beginning of the second section of the same essay:

The Yakshagana belongs to South Canara in the Kannada area…For it is the Karnataka country that has named our South Indian music and dance as ‘Karnatic’. In South Canara, the Yakshagana is one of the two most widespread popular dramatic entertainments...The vernacular name of Yakshagana is ‘Bayal Attam’ i.e., open-air play, a name which corresponds to the Tamil ‘Terukoothu’ and the Telugu ‘Veethi Nataka’ both of which mean ‘street-play’.[2]

Dr Raghavan writes further in the same article that Yakshagana was named after the community called Jakkula in the Guntur District; the name yaksha (talented in music and dance) is the derivative form of the term Jakkula. He also mentioned that Yakshagana might have developed from folk songs from the same scholar that Yakshagana might have developed from folk songs like ‘Ela’, ‘Jhola’, etc., which might have been utilised for the Yakshagana performances. Dr Raghavan supports this view with a reference to the Fourth Act of Vikramorvasiyam of Kalidasa and some uparupakas (minor plots in a large play), alongside other Prakrit plays in Mithila, such as Parijatapaharana of Umapati.

Dr Pappu Veṇu Gopal Rao, in one of his articles on this subject, has mentioned that the origin must have been in Andhra during the twelfth century.[3] It is said that the first-ever mention in Telugu literature is by Palakuriki Somanatha Sarma in his Panditaradhya Charitra (1280–1340) as ‘adata gandharva yaksha vidyadharadhulu, padedu nadeduvaru’.

A clearer mention is found in Srinatha’s Bhimesvara Purana (Chapter 3 verse 65) where he says, ‘kirtintu reddani kirthi gandharvulu, ananda garvamuna yakshaganasarini’ (the Yakshaganas were praised by the Gandharvalu and they proudly presented this).[4] It is true, that such a mention points towards a probable connection between the yakshas and Yakshagana, the art form. But authentic documentation is unknown with regards to what bearing the celestial Yakshas had on Yakshagana, which has survived as a literary and musical composition in the Dravidian languages for over seven hundred years.

The modern performances of Yakshagana, either in music or dance, have come a long way since the time of its origin, in Telugu, when the term ‘Yakshagana’ was used for the script or the writing aspect of the work, but not applied to its performance, as used in Kannada as ‘Yakshagana Atta’. The terms used for the performance in Telugu are ‘Viti Bhagavatam’ or ‘Viti Natakam’. In early Yakshaganas, the short prose passages of connecting links that were introduced subsequently into it were uttered by the sutradhara (the prime conductor) who introduced the play and the characters.

Yakshaganas can be classified into three categories:

- Those written just for the pleasure of reading and listening: sravyamulu

- Those fit to be staged: drsyamulu

- Those fit for both: sravya and drsya Yakshaganas

Based on their utility, the drsya kind of Yakshaganas are classified into four categories:

- Viti natakas (street play)

- Bommalata (puppets)

- Marga natakas (classical theatre)

- Modern dramas (contemporary themes)

The Kuchipudi Yakshaganas and the Bhagavata Mela Natakas of Melattur come under the third category. Yakshaganas may be considered as one of the richest aspects of our literature, given that it has been a successful tool in bridging the gap between the elite and the masses with its varied content—music, literature and dance. Bhagavatula Lakshminarasimham, the great-grandson of Bhagavatula Ramaiah Sastri, who authored Golla Kalapam, was born into a traditional family of Kuchipudi and has written several articles. In one of his articles, he has described Yakshagana as an aesthetic literary fete—a fine combination of dance, music and literature. Thus, it may be said that Yakshagana is a comprehensive form of art that assimilates various components, such as Kalapam, Prabandham, Koravanji, Viti Natakam, Bommalata, Harikatha, Marga Nataka, etc. within its structure. Even in terms of content, Yakshaganas cover almost every aspect of literature—historical plots, Pauranic epic stories, social commentary, folklore, philosophical ideas and so on. Though Yakshaganas with sringara as the dominant rasa are prominent, many depict other rasas as well. Thus, Yakshagana occupies a unique place in our literature.

As mentioned before, a Yakshagana is conducted by the sutradhara. His spontaneous commentary enlivens the performance, besides providing continuity. The main objective of this character is to kindle the spirit of drama as the main event and introduce the characters which are thematically drawn. In Kuchipudi, every generation is fortunate enough to have a stalwart as the sutradhara. Their versatile contribution becomes guiding principles for all the succeeding generations. Among such galaxy of veterans, mention may be made of ‘Laya Brahma Apara Satyabhama’ Vempati Venkatanarayana. He portrayed the character of Satyabhama skillfully. He donned different characters and yet left indelible marks in each one of them.

Kuchipudi artistes are strict adherents of tradition. In the Kuchipudi style of dance dramas, the traditional characters are very important—they stand as a symbol of high didactic sense. In almost all the Kuchipudi plays, one invariably comes across such characters. Siddhendra Yogi, the prime exponent and stalwart in Kuchipudi style, led a saintly life with a purpose. He composed several Kalapam-cum-Yakshaganas. He had set up a code of ethics and a discipline for the artistes of Kuchipudi.

With regards to the dance steps of Yakshagana, we look at how they have influenced, apart from the Bhagavata traditions, the Kuchipudi group presentations, dance dramas and solo repertoire, and we find that in all these the Natyashastra plays an important role, but we find a lot of desi or indigenous styles in almost all forms of Andhra traditions, dance and dance dramas. This is because of the dominant impact of the Yakshagana on these traditions, even before it attained classical stature.

Vedantam Parvatisam, the founder member of the Siddhendra Kalakshetra at Kuchipudi, in his writings on the technique of Yakshagana, explains in simple terms the method of performance:

Palikedidi Kuchipoodata, Palikinche bala Nritya Bharati yata – ne, Palikina sastrambagunata,

Palikeda panchaadisutra padagumbhanalan

(The recitation that I do is referred to as Kuchipudi and the words that are said by the dancers which adhere to the Sastra/norms recite the greatness of this fifth Veda.)

Yakshagana is the combination of five sutras or elements (pancha sutras), namely:

1. Natyam (drama with verses)

2. Nrittam (footwork)

3. Nrityam (dance, song and abhinaya)

4. Tandavam (vigorous dance and song)

5. Lasyam (delicate abhinaya and footwork)

Only when all the pancha sutras are incorporated can it be called Yakshagana. This also is the very essence of the solo form that has emerged from this form. Kuchipudi Yakshagana consists of several literary styles—daruvu, kandartha, dwipada yala and alambana.

There is an elaborate process to prepare the stage for the actual Yakshagana performance. The stage is cleaned thoroughly, decorated with rangoli (designs on the floor), festooned with garlands of mango leaves, illuminated with lights, and perfumed with incense. Lord Gaṇesha and other familial/favourite deities are invoked, and songs and prayers offered to ward off all obstacles. This is known as melavimpu. Nowadays the practice is to invoke Lord Ganesha and Goddess Saraswati through dance.

In earlier days, in addition to the prayers, they used to sprinkle holy water, flowers and consecrated rice (mixed with turmeric) near the pillars in all the four corners of the stage while chanting the hymns, and later the ganapati prarthana would be recited.

Yakshagana is explained precisely as songs sung in accordance with drumming.

The most important aspect of the Yakshaganas is their structure, which made them adaptable for almost any other form of performing art. Let us examine some of the salient aspects of the structure of Yakshagana.

A very important feature of Yakshagana is daruvu, which is nothing but dhruva defined by Bharata in chapter thirty-two, verses twenty-three and twenty-four, of Natyashastra. Daruvu or daru originally meant ‘drumming’ in Telugu. Gradually the word has come to mean the song sung in accordance to drumming. Daruvus have great content, and as per the Natyashastra, there are five kinds of darus and all the five kinds are used in the Yakshagana.

Of the five dhruvas mentioned by Bharata, the pravesiki dhruva (composition to narrate character entry) is equivalent to pravesika daruvu used in Yakshagana. While one of the prominent aspects of Yakshagana structure is pravesika daruvu, it is also a salient feature of the Kuchipudi and Bhagavata Mela dance dramas, where the character introduces himself/herself. Apart from this form of daruvu, there are other kinds of daruvus in Yakshagana that are used for different purposes. Daruvus are employed to describe a character, entrance of a character, the character speaking about himself, conversational daruvus, description of nature, the narration of an episode of the drama, and so on.

The ragada (the grammatical metre of storytelling), which adds to the narrative of the story, is another major content in the literary aspect of Yakshagana. One finds that after the ragadas and daruvus, the third most important constituent of a Yakshagana is dwipada (couplet). There is hardly any Yakshagana in which the dwipada metre is not employed. The Sangita Ratnakara mentions the characteristics of dwipada in chapter four, verses two-hundred and fourteen to two-hundred and seventeen. Various kinds of dwipada are employed in Yakshaganas and this process continues uninterruptedly in almost all the Kuchipudi dance dramas, even today.

Another component of Yakshagana structure is padyam (verse). Both the desi (folk) and margi (classical) metres are employed by the authors of Yakshaganas and this is followed scrupulously by the composers of Kuchipudi dance dramas from the days of Siddhendra Yogi, till today. But the real reflection of the Yakshagana characteristics in the Kuchipudi dance dramas lie in the artha padyas (half verses) like kandarthams (interpreting the kanda or verse through abhinaya) and seershathams (interpreting the essence through abhinaya). The first half of these are verses and the latter halves are daruvus.

It is a practice in some of the Yakshaganas to prescribe the names of raga and tala to the kandarthams. If we examine the kandams and kandarthams in the Kuchipudi repertoire, it proves that there is a very great impact of the Yakshagana structure on them. The poem at the end of the famous letter of Satyabhama to Sri Krishna is a kandam (two-line verse):

. . . chittha juni baarikorvaka thatthara padi vrasinanu tappo oppo kopamnechakaittari brovanga rave iviye pranathul

(In the Bhama Kalapam, Stayabhama laments while writing the letter to her beloved husband Krishna)

(Vedantam Parvateesam Bhama Kalapam)

In fact, there are several metres employed in almost all of Dr Vempaṭi’s latest dance dramas. In Yakshagana, we find many prose lines to link the lyrics, and in conversations. This tradition is also adhered to in the Kuchipudi dance dramas. There are a few varieties of them: curnika, kivaram, vinnapam, etc. While Curnika normally contains only Sanskrit, Kaivaram is a prosaic composition that contains eulogy with many Sanskrit compounds. It is usually used at the beginning of the dance drama, immediately after the nandi padyam or the introductory verse.

Another feature frequently employed in Yakshagana is the conversational lyrics, the samvada geyas. We find these in abundance in almost every Kuchipudi dance drama. Conversations between Satyabhama and Sri Krishna, Rukmi and Rukmini in Kalyana Rukmini are all popular.

The music in Yakshagana is traditional and different from concert music. Though the music is in traditional Carnatic ragas—they have a unique tradition of singing the daruvus, kandartham, padyam, kriti, and other compositions.

Some of the ‘rakti ragas’ employed in Yakshaganas are Mukhari, Dhanyasi, Bhairavi, Todi, Kanada, Kambodi, Saurashtra, Bhupalam, Saveri, Regupti, Bilahari, Nata, Arabhi, Madhyamavati, Pantuvarali, Janjhoti, etc. Most of these ragas are employed in both Kuchipudi and Bhagavata Mela tradition. In the Kuchipudi tradition, we find the following ragas used exclusively: Nata, Mohana, Saurashtra, Arabhi, Kamas, Madhyamavati, Anandabhairavi, Todi, Kamboji, Mukhari, Pantuvarali, Devagandhari etc.

Yakshagana thus influenced both the Kuchipudi and Bhagavata Mela traditions and continues to do so. To this day, concerning its evolution, we can arrive at the facts that Yakshagana, Bhagavata Mela Kalpam and solo repertoire are often inter-related, notwithstanding the gender preferences.

Bhagavata Mela Nataka

Sunil Kothari, in his book Kuchipudi, has traced, that in the wake of the decline of the Vijayanagara Empire, a mass migration of many Telugus into Tamil Nadu, and especially to Tanjore was witnessed, which for centuries was famed as a seat of culture. This migration seems to have begun as early as the fourteenth century CE when Kamparaya, the son of Bukka I, led his famous expedition against the tiny kingdom of Madura which was then under the control of a Muslim rule (Madurai Sultanate), and among the immigrants were Telugus and Kannadigas.

Such a wave of migration swept over the Tamil province in the sixteenth century CE as well, when both Tanjore and Madura kingdoms came to be established, with high dignitaries of Andhra origin as their rulers, namely, Sevappa Nayaka in Tanjore and Vishvanatha Nayaka in Madura. The immigrants from Andhra country settled in Tamil provinces. Among those who left Andhra Pradesh after the decline of the Vijayanagara Empire were several Brahmin families of different sects and sub-sects, such as Niyogi Brahmins and Vaidiki Brahmins of Mukkanada Kavalanada areas, who settled in the Tanjore district.

During the reign of Acyutappa Nayaka (1572–1614 CE), son of Sevappa Nayak, it is likely that some of these Brahmin families settled in Tanjore and the nearby areas. The endowments given to the Brahmins by Acyutappa Nayaka included the gift of present-day Melattur village. It is believed that these Brahmins developed the art of Bhagavata Mela Nataka in the six villages, viz. Melattur, Nallur, Teparamanallur, Sulamangalam, Saliyamangalam and Uthakadu.

During this period and the succeeding period of Vijayaraghava Nayaka (1572–1673 CE), great masters of music and dance flourished under the royal patronage. The two most important works on classical Karnataka music, viz. Sangita Sudha and Chaturdandi Prakasika were produced during this period. It was also during the time of Vijayaraghava Nayaka that the great composer-poet Kshetrayya emigrated from Muvva near Kuchipudi village. It was at this time that Tirthanarayana Yati’s Krishna Lila Tarangini inspired other composers to model their works on his grand opera, and the tradition of the dance drama received a great impetus.

With the wave of the Bhakti movement, the other forms like Kathakalakshepam, Harikatha, Bhajan and similar expressions of Bhakti contributed to the right ambience for the art of dance dramas to develop into a vehicle of performing art. Tirthanarayana Yati was a sannyasin of Advaita philosophy. At Varahur in the Tanjore district, he composed and dedicated his musical play on the story of Lord Krishna from his birth to his marriage with Rukmini. The disciples of the saint continued the tradition of dance drama to propagate Bhakti. Thus, the continuity of the Kuchipudi dance-drama tradition can be seen in the Bhagavata Mela Nataka form. Among the disciples of Tirthanarayana Yati, the name of Gopala Krishna Sastri deserves special mention.

Noted pioneer late E. Kirshna Iyer also took great pains to bring the tradition to the notice of the metropolitan audiences in Madras, and the visits by late Rukmiṇi Devi and others brought about the general awakening towards the performing arts. This drew the attention of the public towards the tradition of Bhagavata Mela Nataka, which as an offshoot of the Kuchipudi dance drama tradition, shares many features in common with it.

The structure of Bhagavata Mela Nataka follows the Sanskritic and the Sastraic conventions, as does the Kuchipudi dance-drama form. In Kuchipudi dance dramas, after the preliminaries, a young boy wearing the mask of Ganapati dances, after which the drama begins.

The patrapravesa darus for the introduction of characters, svagata darus for soliloquies, the uttara-pratyuttara darus for the dialogues and so on form a part of Bhagavata Mela Nataka. The nritta (pure dance) aspect that takes after Bharata’s Natyashastra technique with the recitation of the sollus and jatis (rhythmic syllables), are also a part of the dance dramas. The female roles are performed by male dancers. The use of a curtain, held by two dancers on stage is common to both the Kuchipudi and Bhagavata Mela Nataka. The dance drama progresses from one scene to another. Besides songs, there are regular vachanams or prose dialogues. Various other literary verse forms like the padyams, sabdas, slokas, curnikas, padvarnams, sisams, sisardams, kandams, kandarthams also feature in Bhagavata Mela. On the whole, the impression is one of remarkable synchronisation of music, speech, dance and abhinaya (lit. facial expression), producing a highly aesthetic appeal—the ultimate rasanubhava. The music is classical Carnatic and differs in its application from Kuchipudi, though the genres have a common fundamental base.

Today, the descendants of the Bhagavataras assemble annually for rehearsals and stage the dance dramas before the Varadaraja Perumal Temple at Melattur.

Viiti Bhagavatam

During the times of Siddhendra Yogi, participating in Kuchipudi dance dramas was the exclusive prerogative of the male dancers. Gifted male dancers performed female roles and won legendary fame, surpassing female actors. However, there were some exceptions to this tradition as well. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, a few pundits well versed in the art of dance drama and the Natyashastra migrated from Kuchipudi and settled down at Pithapuram, Mandapeta and Amalapuram. Some went to Eluru, Cintalandi or Cattappuru and they came to be known as Bharatamvaru. Most of them imparted training to female dancers and produced their version of the Kuchipudi dance drama repertoire, thus developing a derivate solo performance called Viti Bhagavatam.

Kothari (2001) elaborates that the female artists, generally from the courtesan families, experts in Sadir Nautch (an earlier form of Bharatnatyam), were trained by the Bharatamvaru in their repertoire. Independent of the Kuchipudi dancers and their troupes, these female dancers popularised Viti Bhagavatam. Bharatamvarus instructed the Kalavantulu (devadasis) into a sustained Bhagavata lore. Viti Bhagavatam is performed in open in the street or before a temple at night. The female dancer appears from behind the curtain. In the beginning, nandi (invocation) is sung in the traditional Nata raga, and invocations in praise of Vinayaka, Saraswati and Nataraja are rendered.

Viti Bhagavatam has in its repertoire two Kalapams, viz, Golla Kalapam and Bhama Kalapam. These Kalapams feature only one principal female dancer. Sometimes a Brahmin joins in Golla Kalapam to put across the argument succinctly. He also provides humour and commentary and acts as an interlocutor.

Golla Kalapam has many versions. The first one was composed by the saint-poet Tarigonda Vengamamba who had dedicated herself to the service of Lord Venkateshwara. Her famous works include Venkatachala Mahatmya and Dvipada Mahabharata.

Kothari (2001) talks about the Turpubani, the eastern style of Viti Natakam, which is prevalent in the eastern part, i.e. villages near Vizianagaram. (Fig. 6) The performing artists belong to the community of the goldsmiths, but some of them have turned to agriculture, and aside from practising the art close to the folk form, they present Kalapam with a variation. The hastas (hand gestures) they use are not clearly defined or articulated, nor is the nritta. The dancers sing while dancing and the form appears as essentially a music-oriented Bhagavata tradition. Kurcela Brahmananda Bhagavatara, one of the well-known artists of the group, has carried on this tradition by training his daughters Anjali, Lakshmi and Ratnam. The whole family performs together. They have in their repertoire Bhama Kalapam and Golla Kalapam. In their presentation, the music orchestra stands behind the dancers. ‘Kshirasagara Mathanam’ is one of the popular performances in this genre. Nidugonda Bangarayya, Potala Sammasayya, K. Ramalu, B. Chittibabu, Doodala Saranaiah from Sigdam in Shrikakulam and others are well-known artists of Vidi Bhagavatam.

The Emergence of Solo Repertoire

Dr Shatavadhani R. Ganesh, a great scholar from Karnataka, has in many of his lectures stressed on the importance of rasa in performance, especially in solo repertoire. The traditional concept of abhinaya as codified in the Natyashastra aims at the evocation of the rasa in the spectator, by stimulating in him the latent possibility of aesthetic experience. The four abhinayas in Natyashastra—angika (body movements), vachika (words), aharya (costume and accessories) and sattvika (intellectual states of emotions)—constitute nrittya in a Kuchipudi solo repertoire.

The Kuchipudi solo repertoire has emerged from the traditional dance-drama nrittya and also genres like Tarangam, in which a dancer balances himself on the rims of a brass plate, presented as a part of the exposition, though unconnected with the theme and story of the dance drama. With the emergence of Kuchipudi as a solo dance form, the abhinayas of traditional dance drama are selected for solo presentation. (Fig. 7)

One of the greatest authorities on Bharata’a Natyashastra and an excellent exponent of Kuchipudi Kalapams was Vedantam Lakshminarayana Sastri (1875–1957). He was a man of vision and had introduced progressive changes into the dance form. He reshaped the format from the ekartha (series of items connected) style of performance to those consisting of independent, disconnected numbers (prithagartha). He added tarangams (verses) of Narayana Tirtha, Ashṭapadi of Jayadeva, Padas of Kshetrayya, slokas from Krishnakarnamrtam and Pushpabana Vilasam to the repertoire.

More importantly, some sections of the dance dramas like patrapravesa darus, the lekha or letter that Satyabhama writes to Krishna; and other sequences are also presented in abhinaya section in a solo repertoire.

As the sole medium of expression, the body is subjected to minute observation. As in the Natyasastra—every movement of the angas, the upangas and the pratyangas, and their relation to the emotions have been explored in the development of the Kuchipudi solo idiom. The hastas (hand gestures) and their usages for expression in a kinetic language to augment the text or libretto further have been fully developed. The body postures, often sculpturesque, are imbued with emotions and reveal, besides grace, the state of mind of a character. Thus, angika abhinaya relates to bodily movements for expression of emotions.

Traditionally the Kuchipudi dancer/actor was trained to sing and deliver dialogues. Vachika abhinaya is an important feature of Kuchipudi dance. In contemporary practice, vachika abhinaya is limited to the song sung by the vocalist and it is left to the dancer to express it in mime. Those who are gifted often render a song and enact abhinaya to it and engage in a dialogue with the sutradhara, the conductor who impersonates the role of the sakhi (female friend). It offers a glimpse into the nature of the dance drama and brings in a dramatic flavour. But in most cases, the vachika abhinaya is limited to the vocalist accompanying the dancer, for music in a solo performance.

Dr Vempaṭi Cinnasatyam codified the adavu (basic steps), cari (step movements), hastas and the karanas (poses) for the angika aspect of abhinaya. In his lecture demonstrations, he has stated that while restructuring the Kuchipudi solo repertoire, he concentrated more on the angika and sattvika abhinaya, and did not use vachika.

In today’s Kuchipudi solo repertoire, a dancer chooses to perform a series of solo dances which are excerpts from the larger Yakshagana and dance dramas. A solo performance will begin with the traditional Purvaranga vidhi which is taken from the Yakshagana and Bhagavata Mela tradition. (Fig. 8) The singers sing the traditional prayers; after which new invocatory dances are performed. This is followed by a Jatisvaram—the abhinaya is introduced in sabdam, which often narrates a brief story or episodes from Bhagavatam or Ramayana, like the Dasavatara Sabdam. Then, Tarangam is the main dance of the repertoire, apart from Bhama Kalapam which is enacted by choosing a few darus. The latter half will have a bhajan or Ashtapadi or Annamacharya or a Tyagaraja kriti. After this, the programme concludes with a padam or a javali and tillana and finally closes with an auspicious mangalam song.

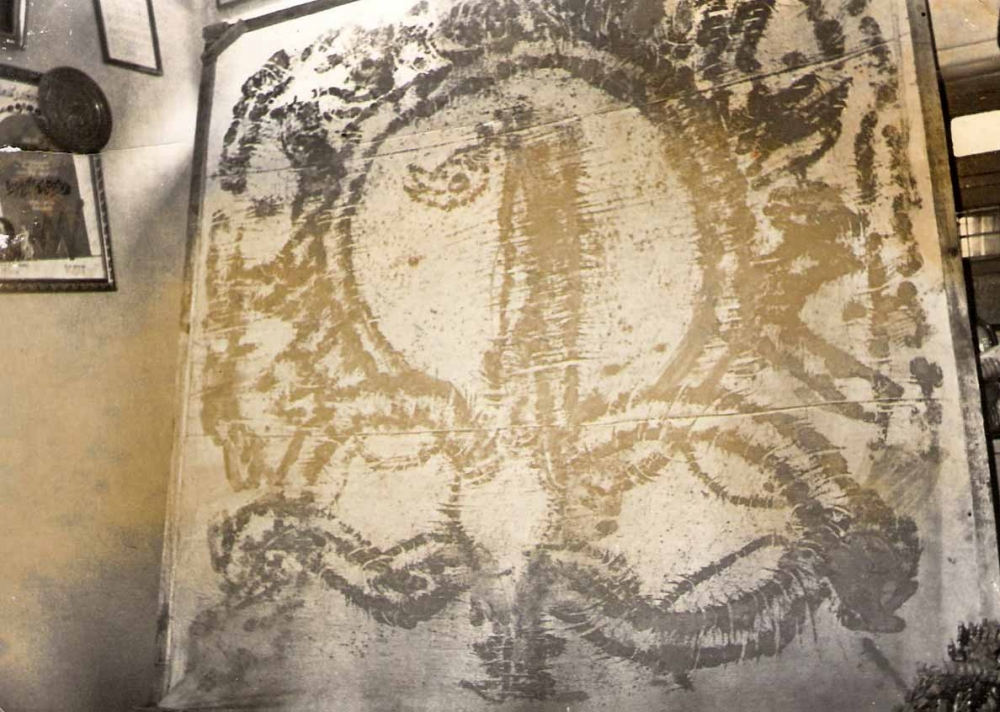

Apart from these dance numbers, a unique dance called the Chitra Nrittya was introduced by Guru Sri C.R. Achrayulu. Rare talas like Simhananadana tala, Mallikamoda tala were composed for dance. (Fig. 9) A picture of a lion is drawn by the feet while dancing to the 128 beats of the Simhanandana tala. The dance is in praise of goddess Katyayini. Likewise, the drawing of peacock and lotus while dancing on the rangoli spread floor is included in the solo repertoire. These were ritualistic dances which were reintroduced with rare caris and karanas into the Kuchipudi solo concert.

To conclude, it can be said that Kuchipudi is a dance form with great scope for research and innovations. Kuchipudi has evolved as one of the most popular Indian Classical styles of dance with a wide scope to present solo performances, duets, ballets, dance dramas, Yakshagana, and all the aspects of Bharata’s Natyasashtra.

Notes

[1] Raghavan, ‘Yakshagana’.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Venugopala Rao, 'Kuchipudi Mahotsav’ 1996'.

[4] Ibid.

Bibliography

Appa Rao, Vissa. The Dance Art in Andhra Pradesh. Hyderabad Library for Manuscripts.

Arudra. Kuchipudi: The Abode of Dance.

Bharata. Natyasastra: Text with Introduction, English Translation and Indices in Four Volumes, edited by N.P. Unni. New Delhi: Nag Publishers, 1998.

Kothari, Sunil. Kuchipudi. Baroda: M.S. University, 1977.

Natarajan. B. Sri Krishnaleelatarangini by Narayana Tirtha, Vol. I and II. Madras: Mudgal Trust.

Raghavan, V. ‘Yakshagana’. Triveni VII (2). Madras Music Academy, 1934.

Rama Rao, Uma. Kuchipudi Bharatam of Kuchipudi Dance: South Indian Classical Dance Tradition. Sri Satguru Publications, 1992.

Raghavan, V. ‘Veethi Bhagavatam’. Sangeet Natak Quarterly Journal (11): 1969.

Satyanarayana. ‘Vithi Bhagavatam: Golla Kalapam’. Journal of the Music Academy of Madras (XXXIII).

Venugopala Rao, Pappu. 'Kuchipudi Mahotsav’ 1996,' a souvenir by Kuchipudi Kalakendra. Bombay,1996, .