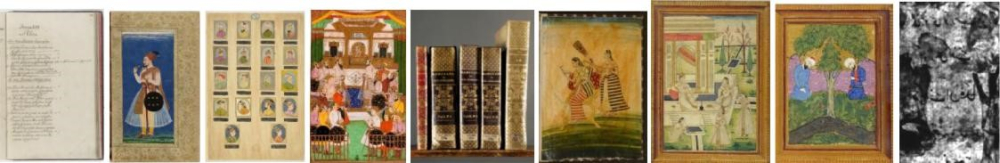

The Dresden Kupferstich-Kabinett (Cabinet of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs) is home to an important collection of Indian miniature paintings. The collection can be divided into two categories. The first category includes works listed in the earliest inventory of the Kupferstich-Kabinett, created in 1738 by the then director of the Johann Heinrich Heucher Collection, along with other Chinese and Japanese artworks under the title La Chine (see Figure 1). It was not until the late 18th century that these artworks were further divided into Sinica (Chinese and Japanese artworks) and Indica (Indian artworks). The Indica category contains four albums of portraits of Indian kings, noblemen, and women, with about 336 portraits in the Indian miniature painting style; an incomplete set of Mughal ganjīfa (playing cards); and a wooden board with 18 portraits of Timurid and Mughal rulers. Interestingly, this set also includes an album with 13 medallion portraits of Asian, European, and African men wearing turbans and jāmās (robes) in Indian habit and two Ottoman volumes dated to 1582, with seven illustrations of traditional Turkish costumes.

The second group in the collection comprises 78 single folios of paintings in the Indian miniature style. These works entered the collection in 1848 as part of the bequest of the Indian philologist and Indologist, August Wilhelm Schlegel (1767–1845). The collection was donated to the Dresden Kupferstich-Kabinett by the Dresden artist Augusta von Buttlar who inherited it as part of her uncle August Wilhelm Schlegel’s estate.

Figure 1: A page from the Heucher Inventory, 1738, where the Indian portrait albums are mentioned. Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Kupferstich-Kabinett Bureau II Histoire naturelle, cat. 1, p. 155.

At the turn of the 17th century, the opulent Mughal Empire attracted a wide array of Europeans to India. Beginning with the Portuguese in the 16th century, along with some Germans and Italians (Subrahmanyam 2017:16), European presence in India expanded vastly in the late 16th and 17th centuries.2 Meanwhile, Mughal portraiture, which had reached its highest level of refinement during the reign of Emperor Akbar (r. 1556–1605), continued under the reign of Jahangir and Shah Jahan, and to a certain extent, Aurangzeb. However, after the defeat of Golconda and Bijapur by Aurangzeb in 1686–87 and during the subsequent decline of the Mughal Empire in the following decades, artistic patronage shifted from being the domain of rulers to that of less notable individuals while European trading increased in the area. Along with written material, art objects became a popular way of representing India. A large part of the Dresden collection of Indian paintings, collected by or acquired for the Elector of Saxony, Augustus the Strong (r. 1694–1733), come from this period—mid/late 17th to early 18th century. They were most probably produced by both Mughal and Deccani artists who established their own workshops due to the closing of ateliers and loss of imperial patronage (Kruijtzer and Scheurleer 2005:52). Under these circumstances, the artists sought new patrons—not only among the noblemen and the rich (Michell and Zebrowski 1999:157), but also among Europeans3—and found a flourishing market, evident from the various collections of Indian artworks in similar styles that now reside in Europe.4

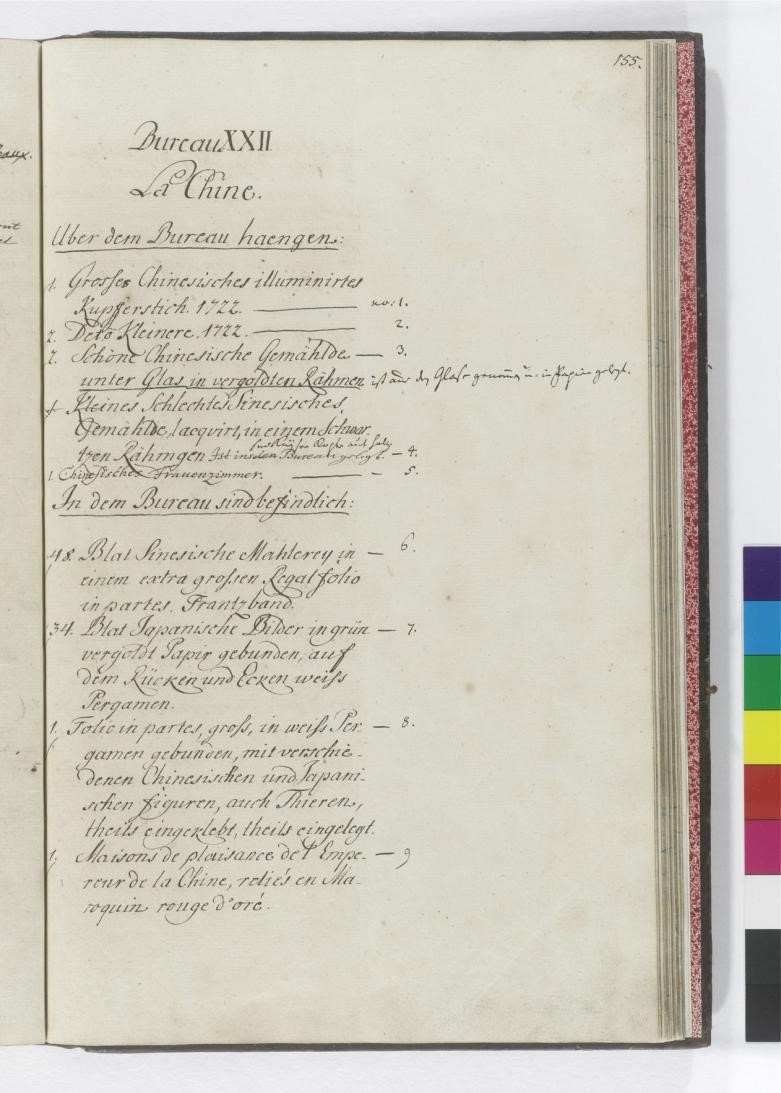

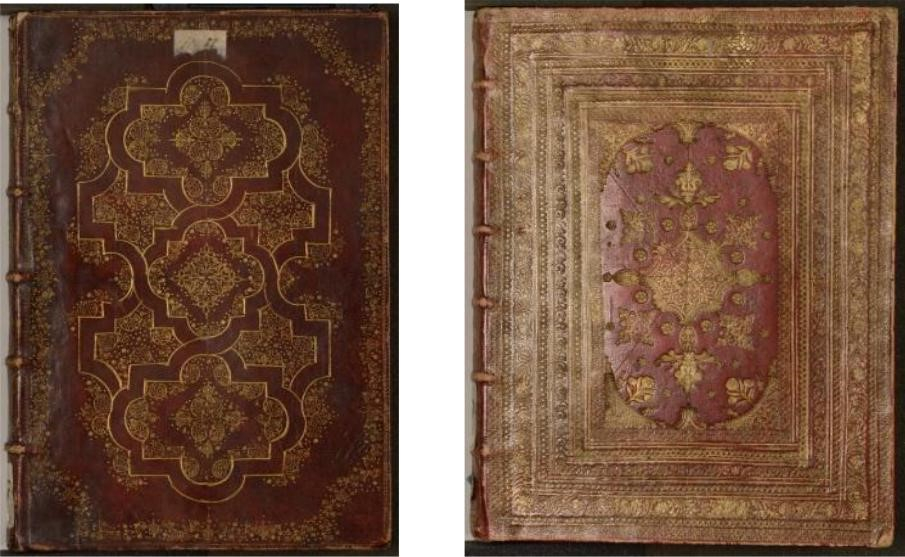

The Indian painting albums in the Kupferstich-Kabinett (inventory numbers Ca 110–Ca 113; Figures 2–5) can be broadly categorised as Deccani–Mughal in style (Berlia 2017:106). They consist largely of individual portraits of Indian rulers and their officers and noblemen—similar to the portraits produced in Golconda in the 1660s for a European audience—and can be grouped into four standard types. The first type has portraits of Timur (r. 1370–1405) and his descendants, including Aurangzeb, and sometimes extend as far as Farrukh Siyar (r. 1713–19).5 The second type includes 179 portraits that represent the kings and queens of India from Raja Yudhīṣṭira to Aurangzeb.6 The third type consists of portraits from Akbar until Aurangzeb, and includes portraits of Golconda rulers, mostly Abdullah Qutb Shah (r. 1626–72) and Abu’l Hasan Qutb Shah (r. 1672–86), and the Bijapur rulers, Muhammad Adil Shah (r. 1627–56) and Ali Adil Shah II (r. 1656–72). Sometimes, there are also a few additional portraits of their dignitaries and the Safavid rulers, such as Abbas I (r. 1588–1629), Abbas II (r. 1642–66), and Sulaiman (r. 1666–94).7 The fourth type includes a selection from the previous three categories, along with other loose sheets, probably remnants of other albums that were dispersed.8

Fig. 2 Fig. 3

Fig. 4 Fig. 5

Figures 2–5:

2. Cover of an album with 39 portraits of Indian kings and noblemen; Golconda (Deccan), late 17th–early 18th century. Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Kupferstich-Kabinett, inv. no. Ca 110.

3. Cover of an album with 72 portraits of Indian kings, noblemen, and women; Deccani Mughal, late 17th–early 18th century. Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Kupferstich-Kabinett, inv. no. Ca 111.

4. Cover of an album with 46 portraits of Persian, Mughal, and Deccan kings and noblemen; Golconda (Deccan), 1668–89. Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Kupferstich-Kabinett, inv. no. Ca 112.

5. Decorated cover of an album with 179 portraits of Indian kings and queens; Deccani Mughal, c. 1680–1710. Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Kupferstich-Kabinett, inv. no. Ca 113.

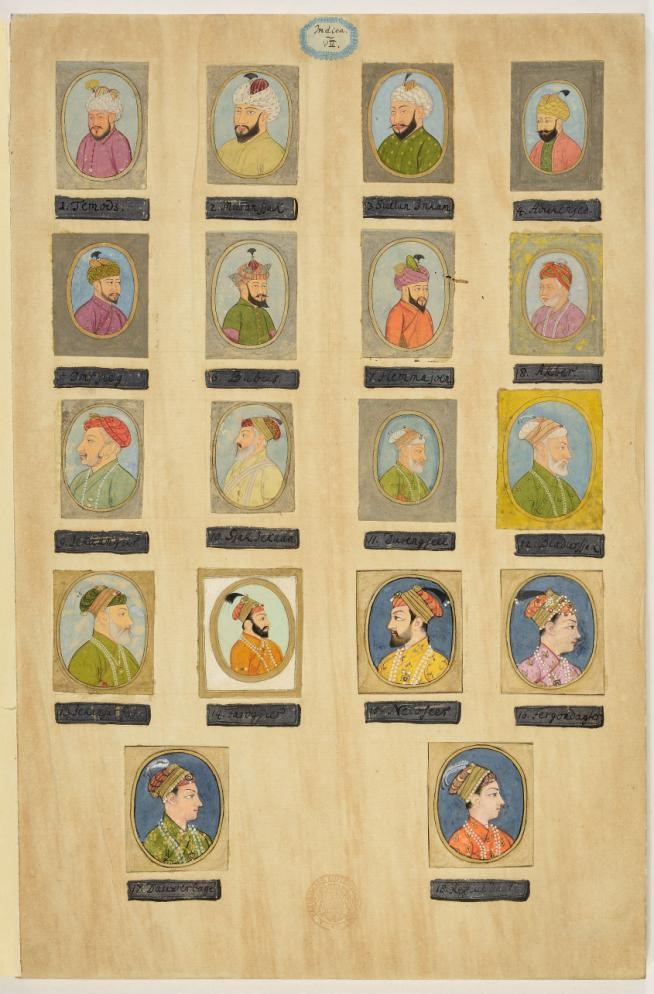

Falling under the second type, Ca 116 (Figure 6) illustrates 18 medallion portraits of Timurid and Mughal rulers mounted on European paper on a wooden board. Registered in the Heucher Inventory as Japanese,9 these portraits, painted in the Indian miniature style, are identified by their Dutch inscriptions, which were probably added after the paintings were acquired by a Dutch collector. Comparative in style and subject, similar series are found in Leiden, Amsterdam, and Vienna, but in larger formats, suggesting the demand for such dynastic representations in Europe.10 Also found in this part of the collection is an incomplete set from a Mughal ganjīfa pack (Dresden, inv. no. Ca 127; see Figure 7). Acquired from the famous collector Nicolas Witsen’s auction in Amsterdam on March 30, 1728, Ca 127 is amongst the third oldest documented set of Indian playing cards that has entered a European collection. Probably from the Deccan region, ‘the uneven execution as seen on the remaining five suits (figurative court cards, such as king, minister and servant are all missing) of the incomplete set in the Dresden collection, reflects the status of its patron'.11

Figure 6: 18 Portraits of Timurid and Mughal Rulers; Deccan, c. 1719; ink, watercolour, and gold medallions, ca 4.5 × 3.2 cm, on paper mounted on a wooden panel, 34 x 22.3 x 0.9 cm; inscribed on mounting paper with the names of the sitters on labels painted in silver and black ink in Dutch; Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Kupferstich-Kabinett, inv. no. Ca 116.

Figure 7: 21 Playing cards from a Mughal ganjīfa pack, now stored in a box, presumably from the late 19th century; Deccan, early 18th century; painted and lacquered cards, each card measures 6.7 x 4.8 cm; Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Kupferstich-Kabinett, inv. no. Ca 127.

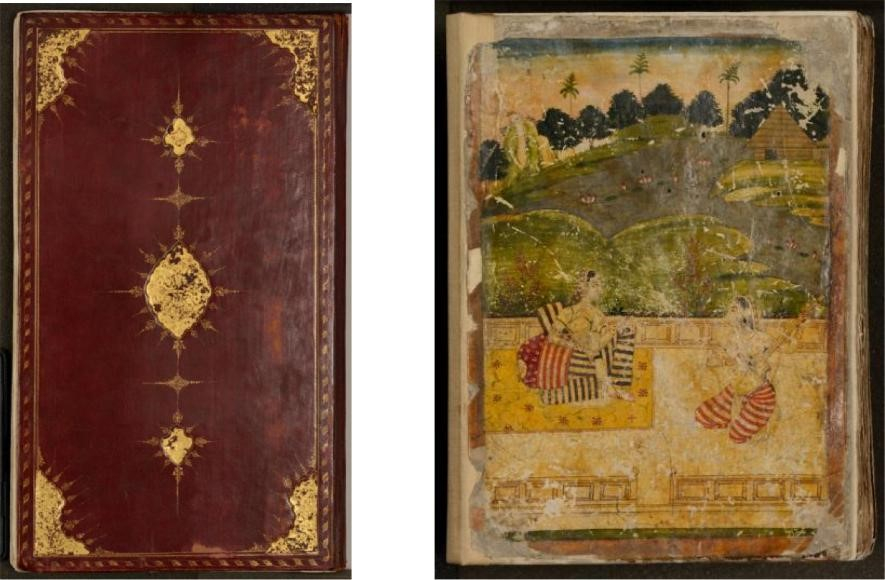

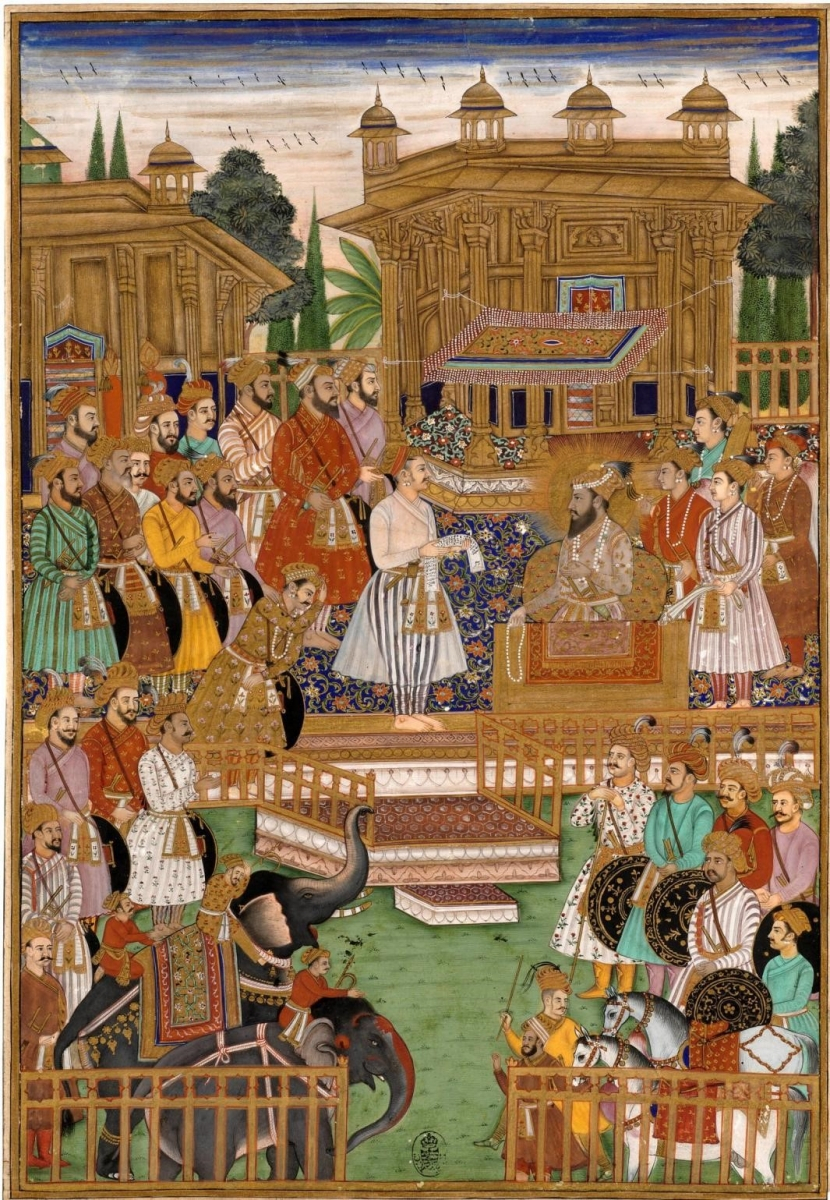

The Schlegel Collection, although from a similar period—mid/late 17th to early 18th century—depicts a much wider variety of subjects and styles when compared to the earlier part of the Dresden collection. In addition to the ruler portraits of the Mughals and their ancestors, beginning with Timur (r. 1370–1405), Rajput rajas, other dignitaries, and court officials, it also consists of various other genres, such as court scenes, royal processions, rāgiṇī illustrations, ascetics, musicians, lovers, and hunting scenes. Stylistically too, the artworks showcase a wide range. The craftsmanship of the artists who had worked in the service of the kings (De Bruin 1737:220) is said to have suffered around the turn of the 17th century, especially for those who formed their individual ateliers involving artists of all capacities, as they quickly produced multiple works of mediocre quality to meet the ‘market’ demand (Bernier 1699:190). While in this part of the collection we find some fine works in the Mughal and Deccan styles (Figures 8 and 9), others are merely simplified versions of the copies produced in imperial ateliers (Figure 10), sometimes with a conundrum of painting styles and motifs that makes it very difficult to attribute them to one particular school. However, the Schlegel Collection successfully provides a fair comparison between changing artistic trends and the exchanges between artists trained at different centres, thereby contributing to our understanding of the shift in the craftsmanship of artists in this period.

Figure 8: Shah Jahan with young Dara Shukoh; Mughal, c. 1680; watercolour and gold, painted frame, 28.2 × 19.1 cm, image 22.8 × 13.7 cm; Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Kupferstich-Kabinett, inv. no. Ca 123/1.

Figure 9: Muhammad Adil Shah (r. 1627–56); Bijapur (Deccan), mid-17th century; ink, watercolour, gold, and silver, painted frame, 17.2 × 14 cm, image 11.3 × 8.3 cm, medallion 8.1 × 6.8 cm; inscribed below in Dutch: Koninck von Visiapour (King of Bijapur); Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Kupferstich-Kabinett, inv. no. Ca 121/7.

Figure 10: Darbār of Shah Jahan; Mughal School in Deccan, late 17th–early 18th century; watercolour and gold, painted frame, 34.3 × 23.4 cm, image 28.1 × 17.6 cm; Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Kupferstich-Kabinett, inv. no. Ca 119/3

Apart from the Indian artworks mentioned in the Heucher Inventory (dated to 1738, of which some were bought from the 1728 auction of Nicolas Witsen’s collection) and the Schlegel Collection (donated to the Kupferstich-Kabinett in 1838), Dresden also houses two precious court scenes that were brought to the court by the ‘African Scholarly Society’—likely an expedition commissioned by Augustus the Strong in 1731.12 The first sheet represents Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb holding darbār (court proceedings) (Ca 125/1; Figure 11) and the second sheet (Ca 125/2; Figure 12) shows Shah Jahan’s morning audience while he indulges in the act of jharokā darshan (Sanskrit for ‘sight’ and ‘beholding’ through a window), both executed in Deccani Mughal style. Furthermore, a masterpiece, the famous representation of Aurangzeb’s birthday scene in the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Green Vault, Throne of the Great Mughal Aurangzeb—featuring rubies, emeralds, pearls, over 4000 diamonds, and a single sapphire (Chow 2015), which was presented by goldsmith Johann Melchior Dinglinger to Augustus the Strong on March 3, 1709, precisely two years after the death of Aurangzeb in Ahmednagar on March 2, 170713—reflects the continued interest of the Elector of Saxony, Augustus the Strong, in Indian artefacts and in his contemporary, the great Mughal emperor Aurangzeb.

Figure 11: Aurangzeb Holding Darbār; Deccani Mughal, late 17th–early 18th century; watercolour and gold, 37.2 x 25.7 cm; inscribed verso (nasta’līq): […] 17 Aurang shah Pādshāh; Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Kupferstich-Kabinett, inv. no. Ca 125/1.

Figure 12: Shah Jahan’s morning audience (jharokā darshan); Deccani Mughal, late 17th–early 18th century; watercolour and gold, 35 x 22 cm; Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Kupferstich-Kabinett, inv. no. Ca 125/2.

Notes

- Heucher Inventory 1738, sig. cat.

- The Dutch established factories at Masulipatnam and Nizampatnam in 1606 and at Pulicat in 1621; the English East India Company established theirs at Masulipatnam and Negapattam in 1611 and at Pulicat in 1621.

- For example, the Dutch East India Company ambassador, Johannas Bacherus, commissioned ‘Camping with the Mughal Emperor’ in 1687 from a Golconda artist. See Scheurleer and Kruijtzer (2005: 52).

- See Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris, Smith-Lesouëf 232 and 233; British Museum, London, inv. nos. 1974 6–17 02, 1974 6–17 04, and 1974 6–17 011; Victoria and Albert Museum, London, inv. no. IM9–1912; Bodleian Library, Oxford, inv. No. MS. Ind. misc. d. 3; Witsen Album, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, inv. no. RP-T-00-3186; Museum für Indische Kunst, Berlin, inv. no. MIK 1 5066–68 and some folios in MIK I 5004; and the collections of Count Abate Giovanni Antonio Baldini and Simon Schijnvoet, reproduced in Chatelain (1719) and Valentijn (1726).

- Ca 116; see also Nationaal Museum for Wereldculturen Leiden, inv. nos. 360–7346–360–7363 and the collections of Count Giovanni Antonio Baldini (1654–1725) and Simon Schijnvoet, reproduced in Chatelain (1719) and Valentijn (1726), respectively.

- Ca 113; see Victoria and Albert Museum, London, inv. no. IM9–1912; and Bodleian Library, Oxford, MS. Ind. Misc. d. 3.

- Ca 112, Ca 110; see Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris, Smith-Lesouëf 232 and 233; British Museum, London, inv. nos. 1974 6–17 04 and 1974 6–17 011; Musée Guimet, Paris, inv. no. 35. 491, 35.492; and Witsen Album, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, inv. no. RP-T-00-3186. Also see Dresden 2017, cat. 10, pp. 140–142.

- Ca 111; see British Museum, London, inv. no. 1974 6-17 02; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Canter Visscher album, inv. nos. NG-008-60-1 to NG-2008-60-28; inv. no. NG-2008-60; Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna, Min. 44 and Min. 64; Museum für Indische Kunst, Berlin, inv. no. MIK 1 5066-68 and some folios in MIK I 5004; and Staatsbibliothek Museum für Islamische Kunst, Berlin, sig. Libri pict. A91. Also see Dresden 2017, cat. 18, p. 155.

- See Heucher Inventory 1738, sig. cat. 1, p. 156: ‘18. Kleine Portraits en Migniature von Japanischen Kaysern auf ein Brethgen gezogen’.

- Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinet, inv. NG-2008-60; Leiden, Museum for Volkenkunde, inv. RP-T-1996-75; Rome, Academia Nazionale dei Lincei, inv. no. 360-7346 to -7363 as well as Österreichische Nationalbibliothek in Vienna, inv. Cad Min. 44, fol. 15 and 16. Information kindly provided by Marta Beccerini and Pauline Lunsingh Scheurleer. Also see, Kuhlman-Hodick (2017:13–19).

- See Dresden 2017, cat. 77, p. 210.

- For the Africa expedition, see Grosse (1902) and Weber (1865). This information was kindly provided by Petra Kuhlmann-Hodick in consultation with Sylvia Dolz.

- See Dresden 2017, cat. 90–91.

References

Berlia, Neha. 2017. ‘From Timur to the Marathas Dynasties of India as Represented in Late 17th to Early 18th Century Portrait Albums in European Collections’, in Dresden 2017, pp. 106–15.

Bernier, François. 1699. Voyage dans les États du Grand Mogol. Amsterdam.

Chatelain, Henri Abraham. 1705–1720. Atlas Historique, Ou Nouvelle Introduction A l’Histoire, à la Chronologie & à la Géographie Ancienne & Moderne. Représentée dans de Nouvelles Cartes, Où l’on remarque l’établissement des Etats & empires du Monde, leur durée, leur chûte, & leurs differens Gouvernemens [...] par Mr. C***. Avec des Dissertations sur l’Histoire de chaque Etat par Mr. Gueudeville. 7 vols. Amsterdam.

Chow, Lesley. 2015. ‘Europe’s Forgotten Treasure Chest: Inside Germany’s Green Vault’. Online at http://edition.cnn.com/style/article/dresden-green-vault/index.html (viewed on December 10, 2017).

De Bruin, Cornelis. 1737. [Cornelius le Bruyn] Travels into Muscovy, Persia, and Part of the East-Indies, Containing, an Accurate Description of Whatever is Most Remarkable in Those Countries, and Embellished with above 320 copper plates. 2 vols. London.

Grosse, Martin. 1902. ‘Die beiden Afrikaforscher Johann Ernst Hebenstreit und Christian Gottlieb Ludwig, ihr Leben und ihre Reise’, in Mitteilungen des Vereins für Erdkunde zu Leipzig 1901, Leipzig 1902, pp. 1–87.

Juneja, Monica and Petra Kuhlmann-Hodick, eds. 2017. Miniatur-Geschichten. Indische Malerei im Kupferstich-Kabinett. Dresden.

Kuhlmann-Hodick, Petra. 2017. Berührungspunkte. Werke Indischer Malerei im Dresdner Kupferstich-Kabinett. Dresden, pp. 13–19.

Lunsingh Scheurleer, Pauline and Gijs Kruijtzer. 2005. ‘Camping with the Mughal Emperor. A Golkonda Artist Portrays a Dutch Ambassador in 1689’, Arts of Asia 35.3:48–60.

Michell, George and Mark Zebrowski. 1999. ‘Architecture and Art of the Deccan Sultanates’, in The New Cambridge History of India, vol. 1, no. 7: Cambridge.

Subrahmanyam, Sanjay. 2017. Europe’s India: Words, People, Empires 1500–1800. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Valentijn, François. 1724–1726. Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indiën, vervattende Een Naaukeurige en Uitvoerige Verhandelinge van Nederlands Mogentheyd in die Gewesten, benevens Eene wydluftige Beschryvinge der Moluccos, Amboina, Banda, Timor, en Solor, Java, en alle de Eylanden onder dezelve Landbestieringen behoorende; het Nederlands Comptoir op Suratte, en de Levens der Groote Mogols; als ook Een Keuryke Verhandeling van ’t wezentlykste datmen behoort te weten van Choromandel, Pegu, Arracan, Bengale, Mocha, Persien, Malacca, Sumatra, Ceylon, Malabar, Celebes of Macassar, China, Japan, Tayouanof Formosa, Tonkin, Cambodia, Siam, Borneo, Bali, Kaap der Goede Hoop en van Mauritius. Te zamen dus behelzende niet alleen eene zeer nette Beschryving van alles, wat Nederlands Oost-Indiën betreft, maarook ’t voornaamste date eenigzins tot eenige andere Europeërs, in die Gewesten, betrekking heeft. Met meer dan thien honderd en vyftig Prentver beeldingen verrykt. Alles zeer naaukeurig, in opzigt van de Landen, Steden, Sterkten, Zeden der Volken, Boomen, Gewasschen, Land-en Zeèdieren, met alle het Wereldyke en Kerkelyke, van d’ Oudste tyden af tot nu toeal daar voorgevallen, beschreven, en met veele zeer nette daar toe vereyschte Kaarten op geheldert door François Valentijn, Onlangs Bedienaar des Goddelijken Woords in Amboina, Banda, enz. in vyfdeelen, 8 vols. Dordrecht/Amsterdam:

Weber, Karl. 1865. ‘Eine Sächsische Expedition Nach Afrika. 1731 fl.’, in Archiv für diesächsische Geschichte, vol. 3, pp. 3–50. Leipzig.

Witsen Nicolaas. 1728. Catalogus van een Heerlyk Kabinet met oost-indische en andere konstwerken […] naargelaten door […] Mr. Nicolaas Witzen […]. De Verkoopinge zal geschieden door de Makelaars Dirk van Hage, Vincent Posthumus, Pieter Kerkhoven en Jan Lempjes […] den 30 Maart 1728. en volgende dagen […] tot Amsteldam […]. Amsterdam.