‘….no photograph can do justice to a scene in which was present such an extraordinary wealth of colour - the orange robes of the Yellow lamas ; the draperies of the red lamas, of various shades from fiery red to purple black ; the red, white, and green dresses of the thronging people ; the numerous rich tones of the painted monastery, and the hanging banners ; the mud-coloured town and crags behind, glaring in the sunshine ; and lastly, above the whole picture, the beautiful blue of the Tibetan sky’ (Knight 1893, 205).

—E.F. Knight (1890) describing the Hemis festival (Fig. 1).

Introduction

Hemis is one of best-known monasteries of Ladakh described in travel literature from the early 19th century by a single sentence; ‘Himis Gompa is the most important and wealthy monastery in Ladak…’ (Knight 1893: 193). Hemis Monastery (Gompa[i]), founded in the 17th century by Stagsan Raspa (sTag-ts‘an-ras-pa), is the seat of the Drukpa Kagyupa sect and was closely associated with the royal family of Ladakh. It is also among the richest monasteries in terms of land holdings (2,500 acres), spread across Ladakh and Zanskar. Some of the important temples of the Drukpa sect under the Hemis administration are Shey, Stok, Mahe, Chumtang, Chusul, Nyoma, Mulbek, Basgo, Khalstse, Skurbuchan, Sumda, Sani Leh, Phugthal and Wanla. The other affiliated monasteries of Hemis, founded almost at the same time, are Chemrey (Chemde), Hanle and Timosgong. The location of these monasteries is in the four cardinal directions with Hemis at the centre.

Hemis is located in Shang Valley of the Stok Kangri mountain range. A road from Karu on the NH 21 (Leh–Manali) leads to a bridge across river Indus rising up to an open space with Martselang, a small village, falling on the left. The road winds along a long mane (prayer) wall and cuts through it leading to a cluster of chortens of different shapes and typology[ii].

High on top of the mountain in vantage locations are several lhato[iii] that mark the perimeter and protect the sacred landscape of Hemis. The road takes several turns following the valley along the stream. The monastery makes itself visible through a line of tall trees, an image capable of surprising even the regular visitors to the place (Fig. 2a). The magnificent view finds expression time and again in travel literature on Ladakh. ‘It was many windowed, and several stories in height; square in shape, with an open quadrangle in its center. At each corner was a square tower, on the top of which flags waved…’ (Torrens 1862: 174) (Fig. 2b).

The social and political importance of the Hemis Monastery also reflects in the cultural manifest—wall paintings, thangka, sculptures and a variety of artistic output that fills the spaces in the monastery.

Historical background

Hemis and, importantly, the Kagyupa (Red Hat) sect in Ladakh have been closely associated with the royal family. Gotsangpa, a student of the first Drukchen (Gyalwang Drukpa), introduced the teachings of Drukpa Kagyupa during his visit to the place. He is also reported to have meditated in a cave called Gotsang[iv] in the Shang Valley, thus consecrating the sacred landscape and establishing the Drukpa association in the Shang Valley.

It was not until the early 17th century that the Drukpa Kagyupa sect asserted its prominence in Ladakhi polity and religious life. This transformation was brought about by Stagsan Raspa Nawang Gyatso (sTag-ts‘an-ras-pa Nag-dban-rgya-mtso), born in 1574 and believed to have lived till 1651. His reputation as a mahasiddha who had met all the 84 masters reached the court of Jamyang Namgyal, the then king of Ladakh. Soon after learning that Stagsan Raspa was in Zanskar, the king extended an invitation; but Stagsan could not acquiesce as he was travelling to other places. Ultimately Jamyang Namgyal’s wish was fulfilled by his son Senge Namgyal who ushered the golden age of Ladakh; Raspa acted as an adviser to the king in his political and diplomatic affairs.

Stagsan Raspa is described as the king of siddhas[v] (Francke 1999: 108) and finds mention alongside Senge Namgyal, who through his reign restored Ladakh to its old glory, extending the borders to include Guge and large parts of western Tibet. Among the most important building projects of Stagsan Raspa was the establishment of a lamasery and the seat of the Drukpa Kagyupa lineage in Hemis, a site significant for its long association with the Drukpa sect and unique location in the Shang Valley.

An inscription found on a mane wall outside the main complex provides information regarding the construction of Hemis. The inscription was first translated by Emil Schlagintweit (1968: 183–188) under the title ‘Historical Document relating to the Foundation of the Monastery of Himis, in Ladakh’. It names the three important personages related to Hemis—Palyam me Drukpa (dPal-mnyam-med-’brug-pa[vi]), Gotsangpa (rGod-ts‘hang-pa) and Stagsan Rasapachen (sTag-ts‘hang-ras-pa-chhen)—and also identifies the builder/architect Paldan Savi lama (dPal-ldan-rtsa-va’i bla-ma ), who is described as having lived in numerous monasteries and being well versed in the ‘ten commandments’[vii]. The inscription further provides the dates for the construction and consecration of Hemis; Schlagintweit’s (1968) work mentions the corresponding dates according to the Christian calendar:

The Erection was commenced in 1644

The monastery was finished (year of consecration) 1664

300,000 Mane (prayer wheels) were put in 1672.

Petech (1977: 52), however, suggests different dates, pointing out that the inscription is from a later date (second half of 18th century), on the basis that the inscription describes the activities of the third Hemis Kushok[viii], Mipham Tsewang Thinlas (Mi-pam Tse-dban-prin-las). According to him the construction began in 1630 when the main temple was built and the great assembly hall (Dukhang) was consecrated after being decorated with paintings in 1638. The now-defunct official website of Hemis seems to concur with the dates mentioned by Petech (1977), identifying, what is today called the Nyingma Lhakhang (old shrine) as the first structure to have been consecrated by Stagsan Raspa.

After the death of Senge Namgyal in 1642, Stagsan Rasapa continued in a preeminent position, arbitrating the succession that led Deldan Namgyal (Bde-ldan-rnam-rgyal) to the throne of Ladakh. Stagsan Rasapa passed away on January 29, 1651 in Hemis. Soon after his death, chortens were constructed in his memory and in 1655 a ceremony of remembrance was also held in the gompa.

Incarnates of Stagsan Raspa

Nawang Sakya Dorje (Nag-dban mTso-sykes-rdo-rje), the second incarnation of Stagsan Raspa, was found in Lahul (Himachal Pradesh). He continued with the construction work undertaken by his predecessor, adding Dukhang Barpa—a large hall with chortens and sculpture—and installing a golden statue of Buddha at the Hemis Monastery (Drukpa Hemis, the second Taktsang Repa[ix]). The succession to spiritual leadership after the second incarnate did not follow the usual process. The successor wasn’t ‘found’, as was wont to happen, but was chosen by circumstances. Around 1739, one of the princes of the royal household was pushed into monkhood to avoid conflict. Under the mentorship of the second incarnate, the prince took the name Mipham Jamspal Dorje ( Mi-pham ’jam-dpal-rdo-rje). Mipham was sent to Lhasa in 1740 (Petech 1977: 106) for higher learning and on his return to Hemis set about organizing the administration of the monastery, including building and painting activities. Popularly known as Gyalsras Rinpoche, his lasting influence on Hemis is evidenced in the fact that, regardless of the process of his selection, he is seen as an incarnate of sTag-ts‘an-ras-pa (106) [x]. Much of the present physical character of Hemis was defined during his time. He introduced the Hemis Festival and the code of conduct for the monks. He invited Palha, an artist from Tibet, to make large applique thangkas embellished with precious stones and thread, the most important being the thangka of Guru Padmasambhava unfurled every 12 years at the Hemis festival.

The third and fourth incarnations of Stagsan Raspa did not present themselves; in effect, after the second incarnation Hemis has mainly been managed by a chugjot (manager)[xi], usually a member of the royal family. The fifth incarnation of Stagsan Raspa was found in Lhasa. Born in 1882, Nawang Jamspal Deleg Gyaltsen received his spiritual teachings from the tenth Brug-cen. After he passed away in 1939, the sixth and current incarnation was found in central Tibet. Nawang Tenzin Chokyi Nyima (Fig. 3b) born in 1941, was ordained by the 14th Dalai Lama. He was enthroned at Hemis in 1945[xii]. He returned to Tibet for further studies; but due to change in the political climate[xiii], he could not return home. Thus, Hemis once again was left without the Kushak. In absence of the incarnate, Hemis was administered through a committee which also had some representation from the local government. The Drukchen (who heads the Drukpa Kagyu school)—recognizing the potential of the monastery and given that access to the mother monastery in Tibet is restricted—has now taken charge with the aim of developing Hemis as core of Drukpa Kagyupa sect.

Hemis architecture

The Hemis Monastery with its Tibetan architectural vocabulary is unlike any other religious structure in Ladakh (Fig. 4a). The site fulfils most of the canonical requisites for building a monastery. ‘Examination and taking possession of the building site: One should seek out a place for building a temple in places that have the following: a tall mountain behind and many hills in front, a central valley of rocks and meadows resembling heaps of grain and a lower part which is like two hands crossed at the wrist’ (Gyatso 1979: 29).

The monastery is imposing with chortens marking its sacred landscape and small monks’ quarters hugging the nearby slope (Fig. 2 a & b). The main entrance leads to a courtyard, a remarkable space surrounded by imposing structures (Fig. 5). Every element of architecture facing the courtyard has at some time or other been removed or redone to accommodate growing number of tourists and to keep up with its new responsibility as the spiritual and religious centre of Drukpa Kagyupa order.

The oldest part of the monastery, called the Nyingma Lhakhang, is at the back of the courtyard; attached to the lhakhang is the kitchen and several ancillary structures now empty. In the second phase of the construction, the Dukhang Barpa (Fig. 4b) and the Dukhang Chenmo—the main prayer hall of the monastery—were constructed. Both are double-storey structures with elegant composite pillars, and attached to them are the quarters of the chugjot (manager).

The roof parapet of the structure is defined by a broad band of red painted reeds coped with stone, and each corner has a large inverted bell-shaped structure that is golden in colour. Rectangular balconies (rafsal) and an expanse of stone masonry with small windows puncture the facade.

The space in front of the prayer halls is enclosed by an L-shaped two-storied structure called the visitors’ gallery. This space is designed for the festival to accommodate the large number of locals and tourists who visit to witness the unfurling of the special thangka and the dance (Cham). The space enclosed by the visitors’ gallery and the main monastery forms the courtyard, a distinct feature of the Hemis architecture with three large prayer flags, one each in front of the two dukhangs (assembly halls) and one in front of the quarters of the incarnate (Fig. 5). In recent years, the gallery has been redone and expanded with structures constructed at one end to house the museum and administrative functions. This has changed the original character of the courtyard.

I. Nyingma Lhakhang

The Nyingma Lhakhang is tucked away behind the main structure of the monastery. It can be accessed through a small courtyard in front of the main entrance of the temple facing south (Fig. 6). The courtyard has a water spring and wood store situated behind it that holds ancient willow stumps.

The lhakhang is 12.45 x 10 metres with the ceiling at about 4.25 metres. The wall to the north facing the entrance has a niche, and behind it—to the north-west—are small chambers originally used as stores for armour and weapons. The roof is held by 12 square columns made of juniper wood mounted with brackets (Fig. 7).

The lhakhang has two large sculptures—Tara inside the niche and Stagsan Raspa, also called Shambunatha (Fig. 8b). Snellgrove and Skorupski (1979) count the murals in the lhakhang among the finest: ‘...it contains some of the finest murals which we have seen in any of the later monasteries.’ They date the paintings to the mid-18th century on the basis of the presence of Shambunatha on one of the walls (Fig. 8 a), however this deduction is contestable. The most plausible dates seem to be between 1739 and 1750 in the time of Gyalsras Rinpoche who was responsible for a number of buildings and decorations in Hemis[xiv].

South wall

The south wall (with the entrance) has three images on either side; they are near-life-size murals of fierce deities. The size and the rendition make these paintings imposing and beautiful at the same time. To the right of the west wall—assuming you are facing the wall—is a four-armed Mahakalla, followed by a wrathful depiction of Manjushri (Jam-dpal), identified locally as Jamspal Tsedag, and Kalachakra (a tantric form of the Buddha). To the left of the entrance are Guhyasamaja, Hevajra and Palden Lhamo (whose image is covered due to her wrathful nature and is opened only for special occasions).

North wall

At the centre of the north wall is a large niche that tapers to a point as it reaches the top. The niche is beautifully painted to give the impression of a cave with rocks and trees. Mila Raspa, one of the Drukpa lineage masters, is depicted following his established iconography. Inside the niche, there is a metal sculpture of Tara.

This wall depicts scenes from the life of Buddha. If a person is coming from the west wall, these scenes will be on the wall to their left facing the niche. Arranged anticlockwise as a cycle is the prophecy of Buddha’s birth, proceeding to the scene of his birth, growing up and witnessing the four sights of suffering, and the great departure. It is followed by depiction of Shakyamuni seated on a lotus throne with his attendants, Sariputra and Maudgalyayan.

Another sequence of the life story of Buddha follows after the visual break that Shakyamuni provides. This sequence has renunciation as the first theme followed by his penance and enlightenment; his first sermon and King Bimbisara offering him the throne are the other themes that form its part. The various scenes from the life of Buddha are loosely organized in a circle but they do not coalesce visually, even though the large blank spaces in the depiction have been filled with landscape patterns acting ostensibly as the uniting factor. There is also a beautiful depiction of the consecration ceremony with King Senge Namgyal and his royal entourage sitting with Stagsan Raspa performing rituals.

West wall

A unique quality of the paintings in the lhakhang is that the various deities painted on each wall seem bound by landscape patterns which form a common unifying element. This is evident also on the west wall of the lhakhang. Large empty spaces have been filled with mountainscapes executed freehand with calligraphic strokes and subtle variations of colour. The west wall has Vajradhara at the centre. He is surrounded by Drukpa lineage masters Marpa, Naropa and Tilopa. To the left of Vajradhara, Stagsan Raspa (Shambunatha) is seated in lalitasana—the iconography is clearly established with the typical headdress and white colour of the robes. Placed below the Raspa is Jambhala Serpo (Kuber) with the royal family seated on one side.

East wall

Paintings on the east wall are completely lost due to water seepage. In 2015, the paintings in Nyingma Lhakhang were painted over by a local artist in order to make them look clean and bright.

II. Dukhang Barpa

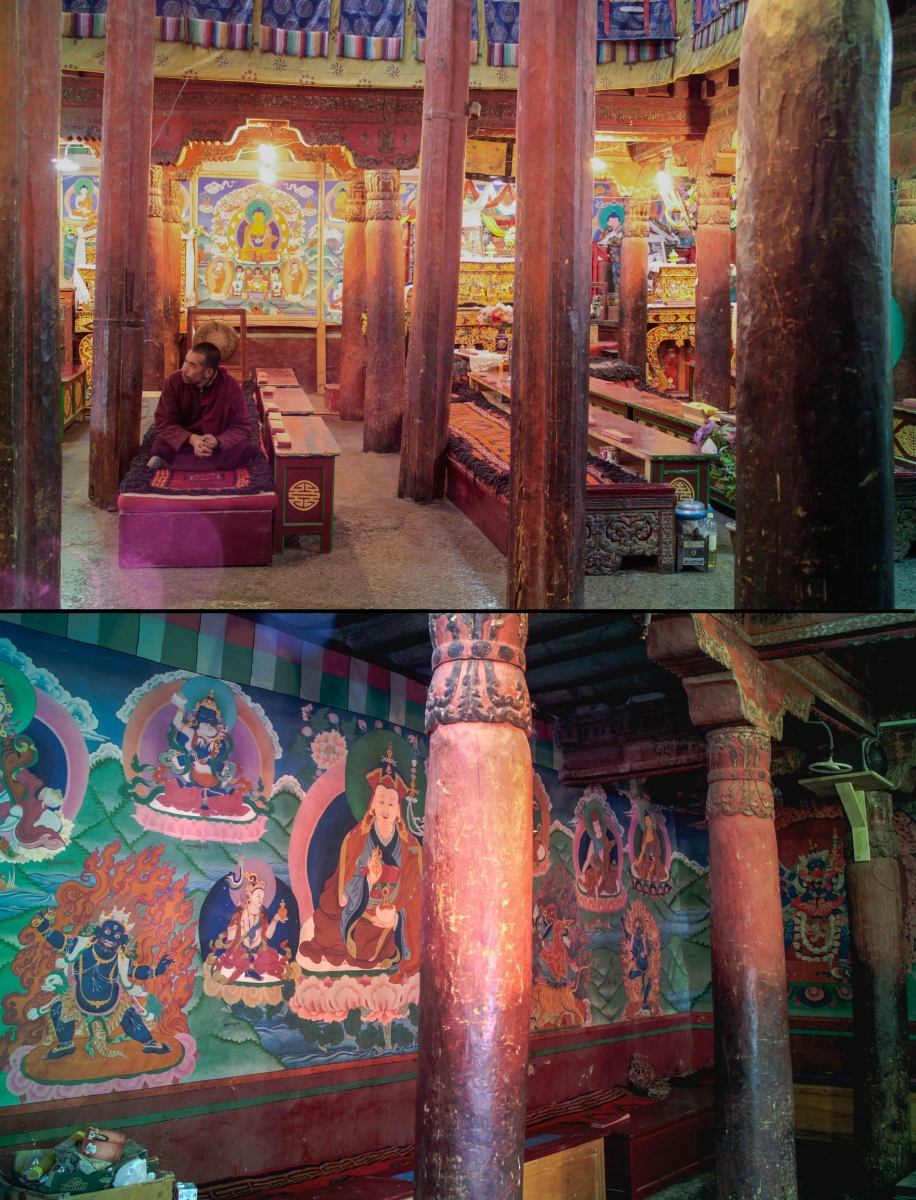

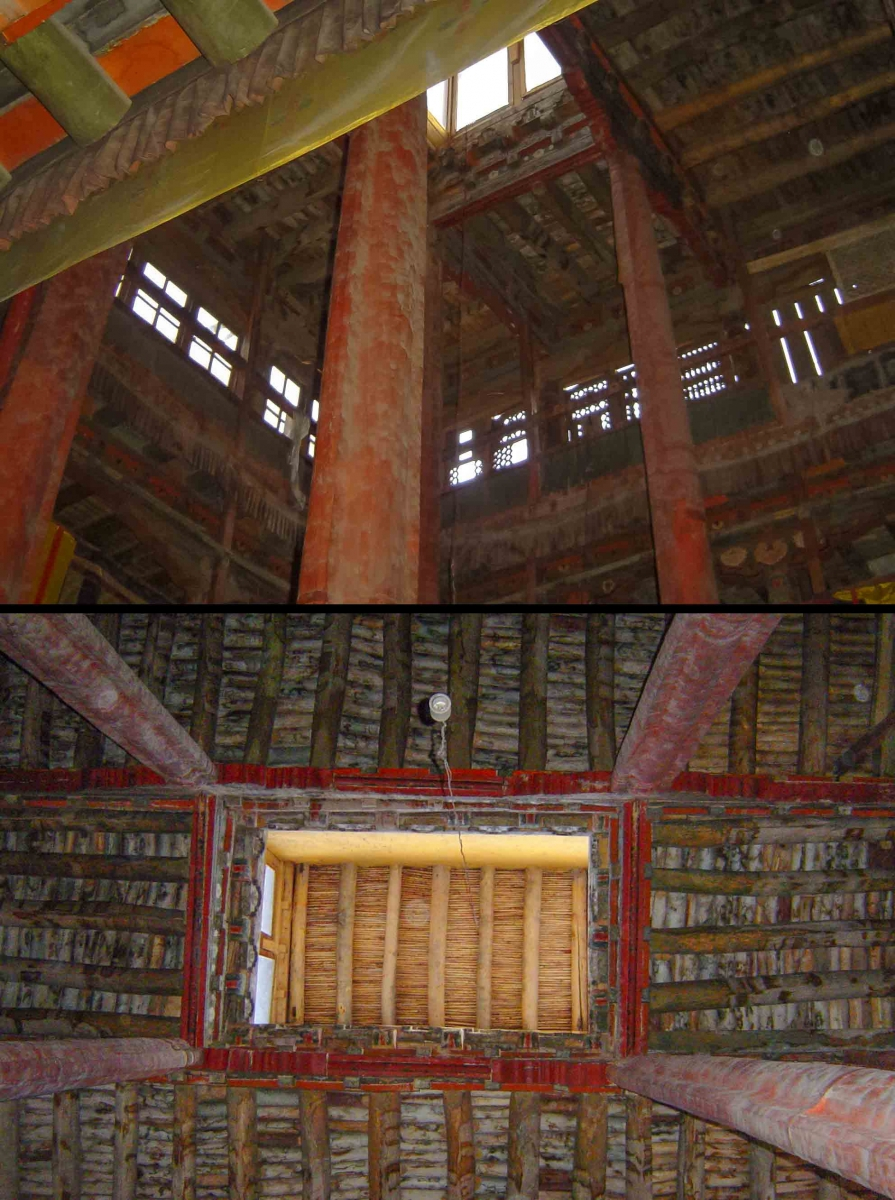

The Dukhang Barpa, or middle prayer hall, is 16.30 x 19.30 metres. Access to the hall from the courtyard is through a short staircase leading to an open entrance porch. The porch has four pillars with decorated capitals holding a decorated beam. The entire area over the porch has slightly protruding balconies with slender wooden pillars accentuating the entrance. Inside the large hall, the roof is at three levels with the roof of the central portion at almost double the height held by composite slender pillars (Fig. 11a).

Fig 11a: View of the central ceiling area of Dukhang Barpa; this configuration of the ceiling is unique in Ladakh—the height is achieved with slender composite pillars and openings to allow light are lined at two to three levels with a walkway. b: View of the central section showing the layout of the purlins with fine willow sticks filling the space. (Photo courtesy Sanjay Dhar)

The hall is used for special occasions. During the Hemis festival, it is used as a dressing and waiting room for the dancers and as a space for the high lamas to sit when they visit. The hall has a prominent Shakyamuni sculpture (Fig. 9), and several stupas and sculptures in remembrance of Stagsan Raspa and Gyalsras Rinpoche.

Dukhang Barpa has rich paintings, a major part of which was repainted as recently as in 2011-2012; the original paintings were damaged due to water seepage over the years. Around 2008, the Hemis authorities first repaired the roof and then commissioned Tsering Wangdus Olthang, a Padma Shri awardee, and his team to redo the paintings (Fig. 9). At the entrance porch of the Barpa are paintings of the four guardian deities along with a depiction of the wheel of life.

North wall

The north wall has some original paintings that have survived the test of time. These remnants provide a glimpse of a past where they, along with other exquisite paintings following the same central Tibetan style, adorned the walls of the hall.

From left to right, when you are facing the wall, is Shakyamuni with 16 arhats. Vajradhara is at the centre with Drukpa Kagyupa lineage gurus and Stagsan Raspa who presides over the hall. Subsequently, there is Shakyamuni surrounded by scenes from the life of Buddha. These scenes are followed by a small niche housing fierce Buddhist deities; the niche is covered with a veil.

West wall

The west wall (Fig. 9) has the five Tathagata Buddhas surrounded by rows of tathagatas of smaller size. If a person is facing the wall, from left to right are Tathagata in the dharmachakra pravartana mudra (turning the wheel of dharma into motion), Tathagata in the dhyana (meditation) mudra, Tathagata in the vitarka (debate) mudra, Tathagata in the abhay (granting the boon of fearlessness) mudra, Tathagata in the bhumisparsh (touching the earth) mudra.

East wall

The east wall mirrors the west in terms of overall composition—five resplendent seated figures surrounded by rows of similar figures. Left to right on this wall are Ratnasambhava, Vairocana, Amitayus, Akshobya and Amoghasiddha. The five main figures are shown seated on lotus thrones, the visible area is filled with gold leaf. Multiple sets of the five bodhisattvas are placed around the main figures in rows covering the entire wall.

South wall

The south wall has depiction of fierce deities. If one is facing the wall, to their left would be Chakrasamvara, Hevajra, Haygriva, four-armed Mahakala (Vjaradhara), Yamri Manjushri and Kalachakra.

Each of the fierce deities has its attendant figures. The paintings that currently adorn the wall have been rendered in contemporary central Tibetan style; however, some of the damaged original paintings have also been retained. In recent years, the gold statue of Shakyamuni has been replaced by a slightly larger sculpture; the original has been moved to a new location.

III. Dukhang Chenmo

A staircase from the courtyard leads to a porch, from where a staircase on the right leads to the first floor to Guru Lakhang. Dukhang Chenmo, the prayer hall, seats the Drukchen and Stagsan Raspa to whom the prayers are dedicated alongside the other masters and deities. Esoteric rituals related to the deities of the order are performed here. From a religious point of view, this is one of the most important spaces in the entire monastery.

The Dukhang is approximately 16 metre by 16 and a half metre, with a double-storeyed ceiling held by slender composite pillars. Close to the ceiling, a walkway runs all along the top—this is used for hanging thangka paintings for rituals and also for maintenance purpose.

The throne for Drukchen and Rinpoche are placed close to the west wall. The north wall has a large display cupboard with sculptures of various deities and lineage masters.

The Dukhang has a long history of chronic water seepage, as a result of which it has been painted several times. Snellgrove (1979) writes in context of the paintings in the hall: ‘The walls have new and rather tawdry paintings on them...’. It is difficult to get a sense of the original paintings in the hall. Between 2012 and 2015, major repairs have been carried out; Olthang has repainted the walls following the original scheme of the paintings. The paintings in Dukhang Chenmo are stylistically very different from the paintings in Nyingma Lhakhang and Dukhang Barpa, perhaps representing the individual style of the Ladakhi artist.

West wall

Shakyamuni and Tathagata adorn the west wall of Dukhang Chenmo.

East wall

Part of the east wall has Guru Padmasambhava and his 10 manifestations depicted.

North Wall

The north wall does not have any paintings; instead, there is a large cupboard with stucco and metal sculptures of the lineage masters, Raspa and Drukchen.

South wall

Starting from left on the south wall are murals of Chakrasamvara, Hevajra, Haygriva, four-armed Mahakala (Vjaradhara), Yamri Manjushri and Kalachakra.

IV. Guru Lhakhang

The lhakhang was built around 1985 on the advice of the Drukchen; it was constructed in place of a dilapidated tantric temple whose roof had partially collapsed. The temple houses a double-storey sculpture of Guru Padmasambhava made by Nawang Tsering and paintings made by Tsering Wangdus Olthang. It has two large composite pillars in front of the sculpture mounted with brackets. The paintings behind the sculpture are in tempera (distemper). Twelve different aspects of Guru Padmasambhava have been painted on canvas with broad wooden frames and mounted on either side.

V. Courtyard gallery

The original visitors’ pavilion at the end of the courtyard had suffered damage in one of the sections due to water seepage. This was rebuilt around 1996, following the original pattern; however the dimensions of the gallery were changed to accommodate more tourists. The gallery building was also shifted back to increase the size of the courtyard.

The visitors’ gallery used to house one of the most iconic painting series of the mahasiddhas, painted low relief and embedded in a wooden structural frame. These have recently been relocated to the first floor of the gallery. The relief paintings of the mahasiddhas are believed to predate the foundation of Hemis. Some believe that the paintings were brought to Hemis from Gotsang, a hermitage centuries older than the monastery; however, no clear information in this regard is available. The treatment of the subject matter is unique and reserved for mane (prayer) wall with mantras carved in low relief.

The 84 panels depicting the great ‘sorcerers’ form the pantheon of the Drukpa Kagyupa lineage, each having contributed to the tantric literature or the attainment of the eight siddhas (Gordon 1998: 94). At the centre over the seat of the incarnate is a large panel of the Shakyamuni with his two disciples; on the other side of the Shakyamuni are the 36 Confession Buddhas.

On the second floor with limited access are Lakhang Tsoma, Gonkhang, Prathok, and Lakhang Khacupa which used to have sculptures in wood (Khacupa is named so because it houses sculptures from Kashmir).

Important materials such as manuscripts, wood blocks, sculptures, decorated textiles and metal objects that were stored in these spaces have now been moved to the large museum building located at the end of the visitors’ pavilion and the library. The museum has a wide range of objects from thangkas to trophies and sculptures dating to the early part of the last millennia, justifying the epithet ‘the richest monastery’.

Hemis Festival (Hemis Teschu[xv])

Hemis Teschu is an important event in the annual calendar of the monastery. The festival was introduced by Gyalsras Rinpoche Mipham Tsewang around 1730[xvi] (Rigzin 1997: 92). It is celebrated on the 10th day of the fifth month of the monastery calendar (May or June in the Christian calendar) marking the birthday of Guru Padmasambhava. The festivities start four or five days earlier as monks from monasteries affiliated to Hemis gather for the preparations. Rituals are performed in various parts of the monastery, Dukhang Barpa being the centre. Monks also practice Cham or the mystical dance with the chhamspon-chheva[xvii] (dance master) to oversee the various logistical and ecclesiastical needs. The main events unfold over the next two days. Specific series of thangka is put up in Dukhang Barpa, and one of the large applique thangka of either the Drukpa teacher, Dadmokarpo, or that of Gyalsras Rinpoche is unfurled on one of the walls overlooking the courtyard (Fig. 15a & b). Masked dances are performed (Gyaltsen 2002; Rigzin 1997) over the two days. On the second day, the large thangka of Gyalsras Rinpoche is unfurled. The events of the day culminate with the performance of Hashang and Hatuk. Hashang is a representation of the Chinese smiling Buddha and the five hatuks are his disciple, they act out scenes from daily life. The performance ends with them distributing apricots to people before returning to the Dukhang.

The other major event related to Hemis is held in the monkey year—once every 12 years according to the Chinese calendar. It is known as the Naropa ceremony (Jina 2004). On this occasion, the six ornaments of the Drukpa lineage master Naropa, made of bones used by Naropa in his Vajrayana practice, are donned by the Rinpoche while delivering the teachings of Chakrasambhava; the Rinpoche also performs special tantric rituals[xviii]. A large applique thangka of Guru Padmasambhava—containing pearls and other precious stones and commissioned by Gyalras Rinpoche—is unfurled in the courtyard; this event is an attraction for the locals as well as the tourists who gather for the festival. The last Naropa at Hemis was held in 2004 under the guidance of Gyalwang Drukchen Rinpoche[xix]. Part of the event has since been shifted to a new location near Shey.

Recent developments, with the Gyalwang Drukpa[xx] (Drukchen Rinpoche), head of the Drukpa lineage actively participating in the administration of the monastery, have seen increased visitor numbers. Since 2009, he has been annually holding the Photang (a meeting of all the Drukpa masters) in Ladakh. This draws a large number of people to Ladakh and to Hemis, as the Photang[xxi] is organized around the time of the festival and is managed by the Hemis administration.

Notes

[i] Gompa is Ladakhi for monastery (a place where monks live) in the sense of the Sanskrit term Vihaara a center with residential quarters, temples and other related functional spaces.

Dukhang or assembly hall, is one of the most important spaces within a monastery complex.

Lakhang is a temple and usually is preceded by the name of the deity to which it is dedicated.

Gonkhang is a space for the tantric practices and home to the terrifying aspects. The Gon-khang is a ‘power place’ representing the vital energy. The place is usually kept secret and the religious practice inside performed only by senior lamas who can on account of their attainments deal with the fierce deities.

[ii] New construction at the start of the perimeter of the monastery has changed the original alignment of the access road to Hemis.

[iii] Is a box like structure filled with a bundles of twigs and sticks with prayer flags and white sashes, often with Ibex skulls meant for the protection of the sacred grounds, monastery and village.

[iv] The Hemis foundation stone inscription mentions rGod-tsan-pa in the list of illustrious monks of the Drugpa lineage who visited Ladakh. (See Schlagintweit’s translation of the inscription in the article).

[v] Siddha (Sanskrit) the perfect one. For basic definition see Gordon 1914: 94

[vi] Spelling as in Sclagintweit.

[vii] Broadly refers to the path for salvation laid by Buddha.

[viii] Rinpoche of the Tibetan is known as Kushak in Ladakhi.

[ix] The main source for information on the latter incarnations and their contribution to the Physical manifest at Hemis is essentially based on the oral history of the monastery, penned for the now-defunct Hemis website.

[x] Petech (1977: 106) notes an instance where Mi-pham ’jam-dpal-rdo-rje is referred to as ‘He-mi sprul-sku (incarnate); this practice has carried on to recent times; Rigzin (1997: 92) initially refers to him as the incarnate.

[xi] The last being Raja Thinles Namgyal (brother of the last king of Ladakh) who passed away recently and has been replaced by the Brug-cen, severing the long tradition of the position being held by someone from the royal family.

[xii] The official version gives the credit to the incarnate, but at six years it is more likely that the managers and the incarnate handlers would have taken all the decisions.

[xiii] I met the Incarnate in 2004 at his residence in Lhasa. He has given up his robes and is married with a family. He was working as a teacher at one of the schools in Lhasa. He was melancholic throughout the meeting and expressed remorse that he has not been able to perform his duties. The secretary of Hemis makes trips to Lhasa from time to time to keep him abreast with the developments and also seeks his approval for any major decisions.

[xiv] This needs to be studied further.

[xv] Teschu is Ladakhi for festival

[xvi] The date does not seem correct as rGyal-sras Rinpoche joined Hemis in 1739.

[xvii] See end note I (Religious Functions).

[xviii] These are referred to as relics and are now annually displayed for ‘Masters and VIPs’ in the Annual Drukpa Council. Ref. Program details of 3rd annual conference; http://www.drukpacouncil.org/en/announce/adc/435-the-3rd-adc-programs

[xix] He first performed the ritual in 1980 and later in 1992.

[xx] Since 2005, he has been annually holding the Photang (a meeting of all the Drukpa masters) in Ladakh. This draws a large number of people to Ladakh and to Hemis, as the Photong is organised around the time of the festival.

[xxi] In 2011, the 3rd Annual Conference was held in Ladakh. The size of the conference is growing with each passing year. For an idea of the extent of organisation, logistical requirements and program for 2011 see http://www.drukpacouncil.org/en/announce/adc/434

References

Drukpa-Hemis. ‘Drukpa Lineage Ladakh India.’ http://www.drukpa-hemis.org/ (last accessed in 2012—the website is now-defunct).

Francke, A.H. 1999. Antiquities of Indian Tibet. Edited by F.W.Thomas. Delhi: Low Price Publication.

Gordon, Antoniette K. 1998. The Iconography of Tibetan Lamaism. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

Gyatso, Thubten Legshay. 1979. Gateway to the Temple: Manual of Tibetan Monastic Customs, Art, Building and Celebrations. Translated by David Paul Jackson. Kathmandu: Ratna Pustak Bhandar.

Knight, E.F. 1893. Where Three Empires Meet: A Narrative of Recent Travel in Kashmir, Western Tibet, Gilgit, and the Adjoining Countries. London: Longmans, Green and Co.

Petech, Luciano. 1977. The Kingdom of Ladakh: 950 -1842. Rome: L'Istituto italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente.

Rigzin, Tsewang. 1997. ‘Hemis the Richest Monastery in Ladakh’. In Recent Researches on the Himalaya, edited by Prem Singh Jina, 91–104. New Delhi: Indus Publishing Company.

Schlagintweit, Emil. 1968. Buddhisim in Tibet. London: Susil Gupta.

Torrens, Henry D’Oyley. 1862. Travels in Ladak, Tartary, and Kashmir. London: Saunders, Otley and Co.

Snellgrove, David L. and Tadeusz Skorupski. 1979. The Cultural Heritage of Ladakh: Central Ladakh. Warminster: Aris & Phillips.

Bibliography

Chandra, Lokesh. Buddhist iconography. New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan, 2006.

Gyaltsen, Jamyang. ‘Hemis Tsechu of Ladakh’. In Development of Ladakh Himalaya: Recent Researches, translated by Prem Singh Jina, 65–68. New Delhi: Gyan Books, 2002.

Khosla, Romi. Buddhist Monasteries in the Western Himalayas. Kathmandu: Ratna Pustak Bhandar, 1979.

Unpublished

Chaturvedi, Anuradha, et al. 1997. Monastic Settlement of Hemis Ladakh: Process for Historic Site Development. Prepared by Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH) in Collaboration with the Institute of Asian Cultures, Sophia University, Tokyo. Sponsored by the Japan Foundation 1997. Vol I (Main Text) Vol II (Condition—Drawings) (Unpublished)

Chaturvedi, Anuradha, ed. 1997. Documentation of Hemis Monastery, INTACH-Japan Foundation Project; Report on Ritual Geography and Symbolisim. Prepared by Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH) in Collaboration with the Institute of Asian Cultures, Sophia University, Tokyo. Sponsored by the Japan Foundation 1997. New Delhi. (Unpublished)

Other sources

Himalayan Art Resources: http://www.himalayanart.org/