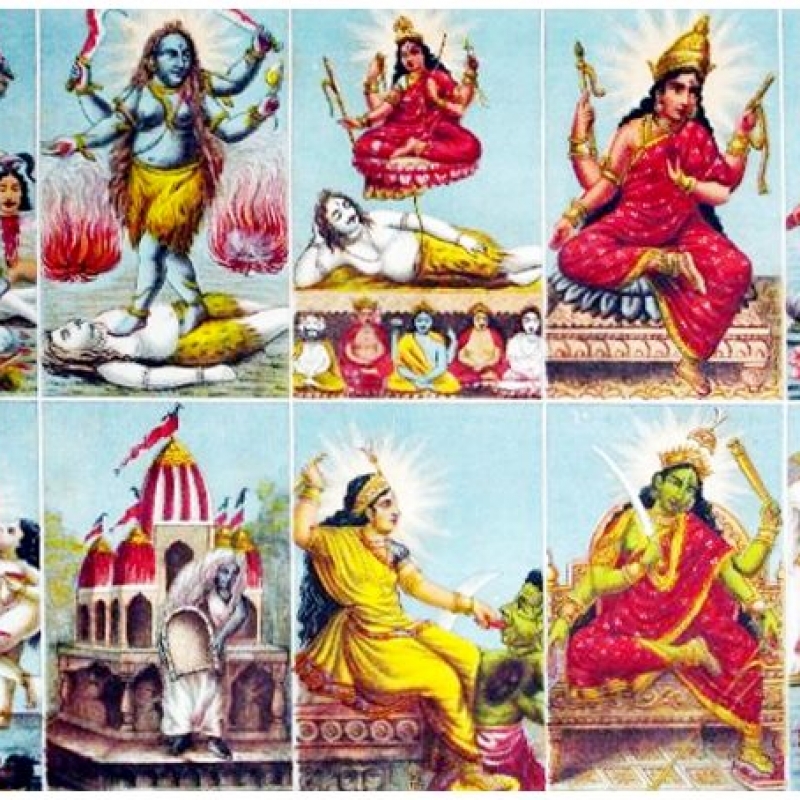

Over the centuries, the Dasamahavidyas and the Shakta Tantra systems have been assimilated and integrated into temple rituals and yogic practices that see the human body and the cosmos having similar structures and intersecting points of energy. The ‘yantra’ of intersecting triangles known as Sri Chakra has come to epitomise all the 10 forms of the goddess (The banner image is a colour lithograph of the 10 aspects of Devi, the divine mother. Each image is identified by a Bengali inscription, and the goddesses represented are, Kali, Tara, Shodashi, Bhuvaneshvari, Bhairavi, Chhinnamasta, Dhumavati, Bagalamukhi, Matangi and Kamala. Photo source: Britishmuseum.org via Wikimedia Commons)

One of the dimly lit areas of Indian knowledge and religious traditions is ‘Shaktism’, which envisioned the supreme being as female. Historians of Hinduism date the origins of Shaktism to the sixth century with the Devi Purana being the earliest text of the theistic movement. Mother goddess worship, however, dates back to the very origins of civilisation in the Indian subcontinent. Devi Bhagavata Purana (11th–12th centuries CE) along with the Devi Mahatmya became the central texts for Shaktism when the movement reached its zenith around 1700. Devi Mahatmya is very popular in the eastern states of India, such as West Bengal, Bihar, Odisha and Assam, and it is recited during the Durga Puja festival. The development of Dasamahavidyas (the 10 great wisdoms) embodies a critical turning point in the history of Shaktism, since their conceptualisation marks the consolidation of several streams of thought and practices across India.

The central story of Devi-Bhagavata Purana narrates the creation of Dasamahavidyas. Sati, the daughter of Daksha and the wife of Shiva, feels enraged that Shiva is not invited to Daksha's yagna (fire sacrifice). Sati nonetheless wants to attend the sacrifice, and questions her father about not inviting Shiva. Unable to get Shiva's permission to attend, Sati becomes further enraged and transforms into the Mahavidyas and engulfs Shiva from all 10 cardinal directions. Thus, the 10 Mahavidyas—Kali, Tara, Tripura Sundari, Bhuvaneswari, Bhairavi, Chinnamasta, Dhumavati, Bagalamukhi, Matangi and Kamala—manifested themselves. The adherents of Shakta Tantra believe that the Dasamahavidyas are the facets of one truth, one divine mother worshipped as 10 cosmic personalities. In the main story, after overwhelming Shiva with her prowess, Sati went to her father's yagna only to be insulted again. Grief-stricken, Sati jumped into the sacrificial fire and killed herself. A furious Shiva destroyed Daksha and laid to waste his entire yagna. Afterwards, maddened by grief, he carried Sati's body on his back and wandered all over the subcontinent, unable to overcome his profound sadness. Sati's bodily parts fell in different places. The 51 places where her bodily parts fell came to be important centres of Shakta Tantra, each hosting a main temple to the goddess. The Kanchipuram Kamakshi Amman temple in Tamil Nadu and the Kamakhya temple in Guwahati, Assam, are two important temples in the network of temples spread all over India. In all these places, even today, we see a strong tradition of Shakta Tantra flourishing. Sati was reborn as Parvati in the Himalayas and married Shiva again, liberating him from his madness and grief.

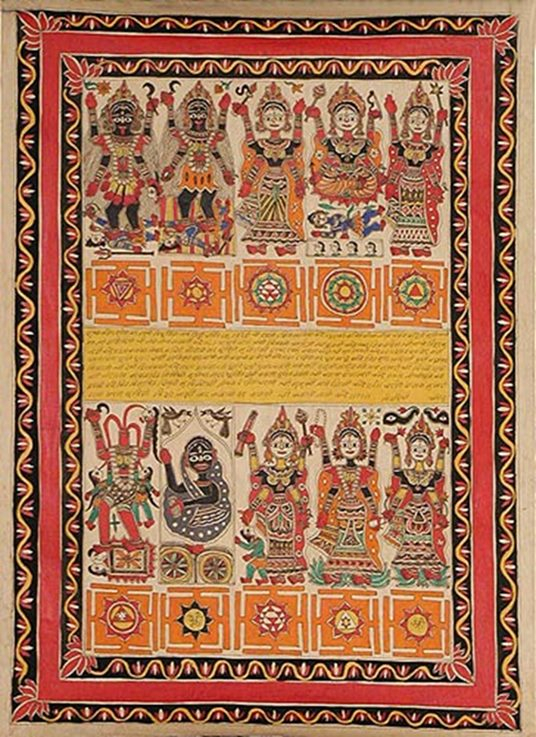

A Madhubani painting depicting the Dasamahavidyas by an unknown artist (Photo courtesy M.D. Muthukumaraswamy)

Over the centuries, the Dasamahavidyas and the Shakta Tantra systems have been assimilated and integrated into temple rituals and yogic practices that see the human body and the cosmos having similar structures and intersecting points of energy. The yantra of intersecting triangles known as Sri Chakra has come to epitomise all the 10 forms of the goddess and Tripura Sundari is considered the Adi Parashakti. The assimilation of Shakta Tantra into ritual practices of Hinduism is attributed to Adi Shankaracharya, the great synthesiser of the multiple streams of Hindu thought, practices and imaginaries all over India. Adi Shankaracharya's Soundarya Lahari (or Saundarya Lahari), as a Tantric textbook, instructs the adherents in the methods of doing puja on Sri Chakra, while eulogising the beauty, grace and benevolence of goddess Parvati/Dakshayani. It is believed that Adi Shankara installed Sri Chakra in many temples devoted to Shiva and to Parvati in her many manifestations.

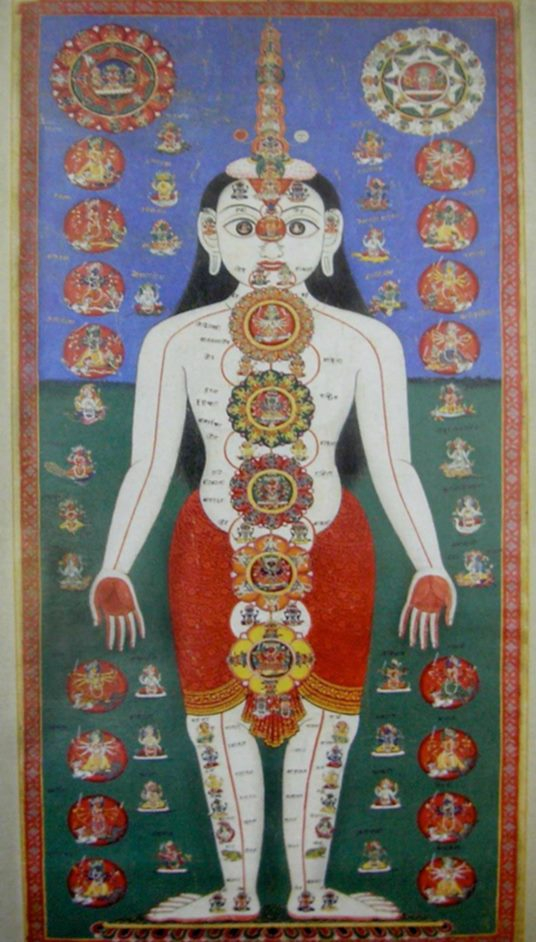

In Soundarya Lahiri, the human body, consciousness and the universe are imagined to have similar mechanisms and structures of intersecting energy points on the material composition of the world. The intersecting circles and triangles of Sri Chakra depict the inner cohesion and connection between the body, consciousness and the cosmos. At each of the intersecting points resides an energy point, a Shakti, a feminine principle, a Vidya, auspicious wisdom which can be envisioned through constant meditation, ritual practice or recital of the mantra. The Soundarya Lahari asserts that the door to the wisdom opens with the recognition that only when Shiva is united with Shakti does he have the power to create.

(left) A Sri Chakra pendant commonly available in markets surrounding of Shakti temples; A metal sculpture from Odisha showing Shakti overwhelming Shiva (Photo courtesy M.D. Muthukumaraswamy)

Douglas Renfrew Brooks, the author of Auspicious Wisdom: The Texts and Traditions of Srividya Sakta Tantrism in South India (1992), writes that in the Shakta worldview, at the moment of creation the cosmos emerges from the Absolute's pure illumination which propels itself into a state of reflective consciousness. Theologically, the illuminative Shiva initiates a reflection of his individuality called Shakti. This act of reflection produces the dualistic universe, which emerges from Shiva's being. From the point of self-reflection onwards, Shiva becomes a secondary figure in the Shakta cosmology. Shakti is the active, manifest and creative component of the universe, and, in effect, subsumes the role of Shiva.

Shiva is the Shakta's reference for the unmoving eternal. As a reflection of eternal consciousness, the One Brahman takes the form of the Self (atman) in each individual. The atman, thus, is identified with Shakti. These cosmological events are paralleled in the human consciousness, and the Shakta Tantra practices on the Dasamahavidyas are geared to awaken this awareness.

In a book published in 2017, Shakti Rising Embracing Shadow and Light on the Goddess Path to Wholeness, Kavitha M. Chinnaiyan has written a modern interpretative scholarly work that can also be used as a practical spiritual guidebook to understanding the 10 Mahavidyas. The Mahavidyas can be seen as creative forces, devotional deities, psychological metaphors, guides to our deep inner work—or better yet, all of the above. Writing that the Mahavidyas make up not only the creative forces on the cosmic scale, but also the forces within us that lead to either freedom or suffering, Chinnaiyan walks us through the binary opposites of shadow and light contained within each of the Mahavidyas. She argues that the shocking or even the repulsive iconography of the Mahavidyas is meant to catapult us out of dualities, such as good and bad, beautiful and ugly, and right and wrong, which fortify the limitations that condition our identity. The images of Mahavidyas allow us to see that nothing escapes the Divine—our shadows are as much a part of its light.

A Tantric painting depicting the vidyas residing in the human body, and connecting to the external world of energy and material (Photo courtesy M.D. Muthukumaraswamy)

Chinnaiyan writes, for instance, that Kali's shadow represents the ‘comparing and judging’, ‘self-righteousness and aggression’, while in her light there is ‘non-violence’. She further writes that Kali is the first Mahavidya because she represents the backdrop to creation: With every step of her dance, Kali destroys the moment before and holds the future in darkness, coaxing us to be reborn into the eternal now. The marvellous paradoxes of existence that Chinnaiyan draws our attention to, while describing dualities of the 10 Mahavidyas are practically new, and make the complex world of Shakta Tantra accessible.

The Dasamahavidyas are indeed a philosophical way for us to imagine a feminine universe and find a path to freedom.

Views expressed are personal.