The tradition of Dalit theatre in Gujarati is as old as the bhavai folk form of Gujarat and has existed since the tenth century. However, it was only created and received attention as a separate category after India’s Independence, especially after the 1970s, with the rise of the Dalit movement in India. During this period, two major trends were visible: plays based on history, myths and legends, and social plays. Most of these plays were published first and performed later or were not performed at all. Dalit theatre in Gujarati is dense and diverse. The broad umbrella term ‘Dalit theatre’ is meant only to categorise and not to homogenise.

Even within the Gujarati Dalit community, which has a shared goal to get rid of caste oppression, there exist different positions and different levels of radicalism. Playwrights like Mohan Parmar and Harish Mangalam provide a peaceful picture of the caste conflict; in their plays, things seem to resolve at the end. The implicit suggestion is that peaceful and harmonious living is possible between people belonging to different castes. Parmar and Mangalam seem to be siding with the argument that as long as Dalits can live with dignity and respect, harmonious living with the larger Hindu society is possible. On the other hand, playwrights like Harshad Parmar, Raju Solanki and Dalpat Chauhan are more radical in their position which is revealed through their plays that indicate an impossibility of any kind of truce. They oppose the entire structure of caste, and their plays indicate that the only way to eradicate caste is through some sort of revolution—at home, street or the royal court. Their position, at least as revealed through their plays, is for an ontologically different category for Dalits, separate from the larger Hindu structure.

Sociopolitical and Literary Context

Following the footsteps of their Marathi counterparts and drawing influence from the Dalit Panthers movement, Gujarati Dalit poets and writers initially began expressing their identity and experiences of oppression through poems. Nirav Patel, Harish Dhobi, Dalpat Chauhan and others began penning their poetry around 1975. Together they used to bring out a periodical called Kalo Suraj (The Black Sun) which included their writings, and they would distribute it in Dalit bastis.[1]

The state of emergency imposed by the then prime minister Indira Gandhi in 1975 and the anti-reservation agitations in 1981 and 1985 all over the country fuelled the Dalit movement. What began with poetry soon encapsulated other forms of writing, like stories, novels, dramas and autobiographies. The period was dominated by Suresh Joshi, with his modernist stance and focus on formal and structural elements of literature. Several of his students and followers populated this period with works that showed finesse and expertise in exploring limits of both language and literary form. From this period of aadhunik yug (era of high modernism), there was a shift to what is termed as anu-aadhunik yug (post-modern era) in Gujarati literary historiography. The rise of Dalit writing marked a clear departure from the Suresh Joshi school of thought, and the focus was reoriented on social context and content in literary works with social realism being the major mode of writing.

As far as drama is concerned, the gap between commercial and amateur or serious theatre existed then as it does now. Drama was and still is a marginal form compared to other forms of writing like poetry and short story. Not many plays by Dalit writers were performed, and those that were closed after a few shows. If anything, this reveals the casteist nature of performance practices in Gujarati theatre. Plays dealing with the issues of caste were written mostly for publication, and cultural institutions like Gujarat Dalit Sahitya Academy and literary journals like Hayati dedicated to Dalit writing encouraged, patronised and published them.

Plays Based on History and Legends

Often, historically marginalised communities assert their voice and identity by invoking heroic figures from history and legends. In the Dalit community, Veer Mayo and Dr B.R. Ambedkar are Dalit heroes who are often invoked, and their life stories are recounted as glorious examples of the resistance of the Dalit community against caste oppression.

Veer Mayo

The legend of Veer Mayo, where the prefix ‘veer’ stands for brave, has been passed on orally from generation to generation right from the twelfth century. The main premise of the legend goes thus: ‘Siddhraj Jaysinh, an illustrious King of Solanki dynasty in the 11th century built a lake called sahastraling. But there were no springs of water in it. The story goes that according to the soothsayers, it needed a human sacrifice. Megh Mayo offered himself for the sacrifice on the condition that the humiliation of Dalits is reduced.’[2] Since there is no historical evidence available, nobody is sure of the facts of the event.

As is often the case in India, history overlaps with folktales. Keeping the story of Megh Mayo as the central premise, several Dalit Gujarati authors have written plays. Krishnachandra Parmar’s play Tipe Tipe Shonit Aapya (Drop by Drop, I Gave My Blood) modifies the magic element in the legend. Parmar portrays Mayo as an architect of the Sahastraling lake. The construction of the lake is so complex that it requires toiling for several days; Mayo devotes himself to its construction and because of the constant hard work that it demands, his health deteriorates, and he eventually dies of tuberculosis. As one can see, Parmar is more interested in the industrious Mayo as opposed to the martyr Mayo.

Shivabhai Parmar’s Maya ni Mahanta (The Greatness of Mayo), while keeping the legend as it is, includes the historical contexts and reasons for the curse on the Sahastraling lake. Mayo is not the protagonist but is one of the main characters in a play full of other more developed characters. Mayo’s final act of sacrifice is what makes him great and provides the play its title.

Shrikant Verma’s Veer Mayo (Brave Mayo), collected in his book Triveni Sangam, dramatises the legend as it is but stresses upon the caste discrimination of the society as well as the state. In the play, eventually, King Siddhraj Jaysingh transforms and is enlightened about the evils of caste.

Dalpat Chauhan’s Patan ne Gondre (At the Borders of Patan), included in his book Anaryavart, is arguably the most nuanced dramatisation of the legend of Mayo and the most scathing critique of the caste structure. Mayo is portrayed as a revolutionary who enlightens the people who had internalised the oppression and were not even aware that they were ill-treated and that they can raise their voice. Mayo inspires the people and is ready to mobilise them against the state; however, Munjal Mehta, the Brahmin minister of Siddhraj Jaysingh, comes up with a conspiracy regarding the Sahastraling lake which requires sacrifice by Mayo. Mayo understands what is going to happen to him, so he puts forth his conditions for the sacrifice, which includes eradication of discrimination and vindication of the dignity of Dalits.

Babasaheb Ambedkar

Like Mayo, Babasaheb Ambedkar is another stalwart upheld as a figure of resistance in plays by Dalit authors. Since the events of Babasaheb’s life are quite well known, we do not find major innovations or exciting interplay of perspectives in plays that are based on his life. Babaldas Chavda has written a children’s play and three full-length plays based on Ambedkar’s life. Baalak Bhimrao Ambedkar (The Child Bhimrao Ambedkar) is a children’s play where Ambedkar’s childhood incidents are dramatised. Chavda’s other three plays, Andhkaar (Darkness), Kraanti-rath (The chariot of revolution) and Betaaj Badshah (A crownless King), include events from Ambedkar’s personal and political life up until his death.

Similarly, Jayanti Makwana’s Yug-Purush (Representative of an Era) and Alok Anand’s Krantiveer Ambedkar (The Brave Revolutionary Ambedkar) are also based on well-known incidents from Ambedkar’s life.

Social Plays

Social plays include the ones set in a modern, contemporary India; they also comprise street plays that were published and enjoyed a ‘literary’ life beyond the performance space.

Contemporary social plays are usually shorter in length and mostly one-act compared to the full-length historical-mythological plays. The reason behind the more elaborate historical-mythological plays could be that myths come with an already existing structure and story, while social plays demand a new story and structure to be created.

In most Indian vernacular languages, Dalit writing had gained momentum by the 1970s, and Gujarati Dalit writing was no different. The anti-reservation agitations in the 1980s only acted as a fuel for the already burgeoning field of Dalit writing. Raju Solanki’s Brahmanvaad ni Barakhadi (Alphabets of Brahmanism), a very political street play that ran for over 25 shows, uses anti-caste agitation as a backdrop and exposes the oppressive regimes of Brahmanism.

Mohan Parmar’s Bahishkaar (Boycott) presents two central female characters, Monghi and Kanaklata, a Dalit and a high caste woman, respectively. Monghi works as a sweeper in the colony Kanaklata lives in; she is treated badly and insulted by Kanaklata following which she stops working at her house. Kanaklata has to face her relatives’ ire due to the untidiness of the house as it was only because of Monghi that the house was clean. Kanaklata realises her mistake and apologises to Monghi, and the play ends on a peaceful note. Monghi in Gujarati means ‘expensive or high-priced’; using Monghi as a central character, Parmar hints at the high price the upper castes pay if they do not treat the Dalits in a dignified manner. Another way of reading the play is that the dignity and self-respect of Dalits are not cheap; their pride cannot be bought easily.

Harish Mangalam takes a developmental issue as the central theme of his play Lyo Chonp Paado (Now Switch on the Light). Set in a village in post-Independence India, the play depicts the harsh realities that many villages face even today. In the play, in a village with limited power supply, electricity does not reach a Dalit household because the upper-caste people do not let it happen as sharing power supply with everyone would mean they would get less of it. The conflict exacerbates and eventually becomes a burning issue. In the end, the government gives in and increases the power supply which provides electricity to Dalit households first and to the Savarna households only later.

Other notable social plays include Dalpat Chauhan’s Harifai (Competition), Kanti Makwana’s Aabhadchet (Untouchability), Sitaram Barot’s Tirango (Tricolour) and B. Kesharshivam’s Raam ni Moorti (Rama’s Idol).

Dalit Plays by Non-Dalit Writers

Umashankar Joshi wrote and published a play called Dhedh na dhedh Bhangi (Bhangi: The Untouchable Among the Untouchables) depicting the oppressive nature of caste as early as 1936. The play created a huge uproar and controversy when published, and was labelled ‘anti-Dalit’; however, as Chauhan notes, the play was later picked up by Dalit authors themselves as a genuine portrayal of caste oppression.[3] Chandrabhai Bhatt, in his one-act play Eklavya (1969) resorts to the mythological story of Eklavya and Drona to point out the unfair caste practices that still exist today. Jashvant Thakar created a folk play based on the story of Mayo, while Dhiruben Patel wrote Bhavni Bhavai, later made into a national award-winning film by Ketan Mehta, starring Naseeruddin Shah, Om Puri and Smita Patil.[4]

There is also Meeta Bapodara’s Swapna (Dreams) which gives us a glimpse into medieval Gujarat. She creates an imaginary village where, once a year, a person from any caste is allowed to be a Brahmin. Prabhu and Babu, a Dalit couple, struggle to make ends meet despite doing manual labour for almost the entire village. Prabhu’s only dream is to be made Brahmin one day, so he can elevate his family and bring about radical changes. The play ends on a tragic note as the Prabhu and Babu die and their son inherits their dreams.

A play that deals with the ideas of pollution and Brahminical snobbery, Keshubhai Desai’s Gobar Gondaji is a story of a conflict between an upper-caste couple and a Dalit man which follows what happens after the Dalit man accidentally touches an upper-caste woman.

Other notable plays by non-Dalit writers are Rajendra Mehta’s Nakalank (Spotless), Durgesh Shukla’s Punaragman (The Return) and Gaurishankar Chaturvedi’s Garibo na beli (The Patron of the Poor).

Notes

[1] Mangalam, Harish. ‘Sacchai ni Najare.’

[2] Gaijan, Dalit Literary Tradition in Gujarat: A Critical Study, 197.

[3] Chauhan, Gujarati Dalit Sahitya ni Kedie, 54.

[4] Ibid.

Bibliography

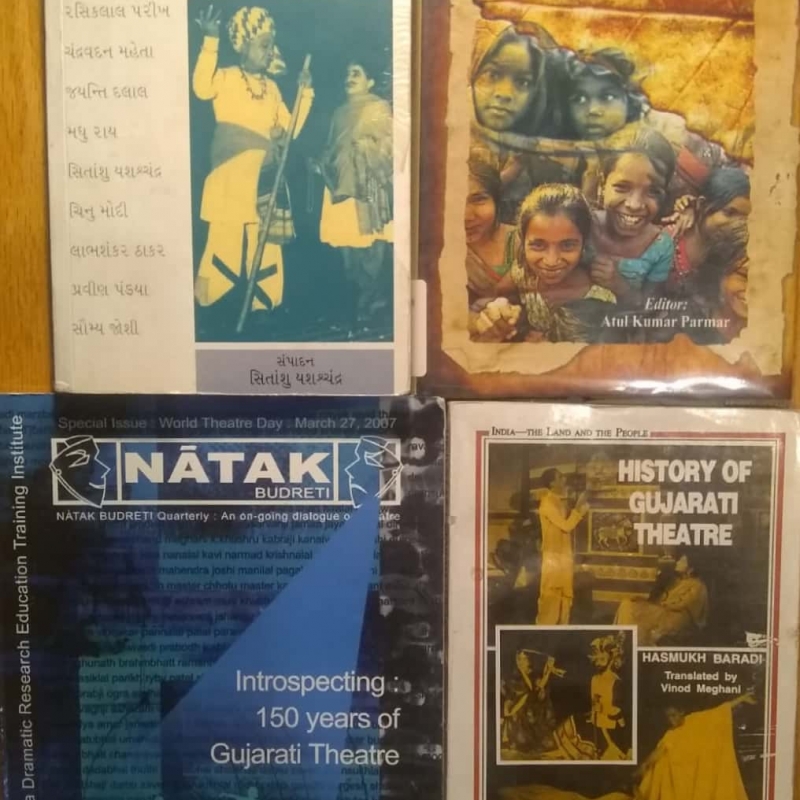

Baradi, Hasmukh. History of Gujarati Theatre. Delhi: National Book Trust, 1998.

Chauhan, Dalpat. Anaryavart. Gujarati Dalit Sahitya Academy, 1988. Ahmedabad

———. Harifai. Ahmedabad: Gujarati Dalit Sahitya Academy, 2000.

Chavda, Babaldas. Betaaj Badshah. Ahmedabad, 2005.

Dave, Jagdish. 'Social Plays: 1851–1900.' In Natak Budreti: Introspecting 150 years of Gujarati Theatre, 127–129. Ahmedabad, 2007.

Dharwadker, Aparna. Theatres of Independence: Drama, Theory and Urban Performance in India Since 1947.Iowa: University of Iowa Press, 2009.

Gaijan, M.B. Dalit Literary Tradition in Gujarat: A Critical Study. Ahmedabad: Gujarati Dalit Sahitya Academy, 2007.

Gandhi, Hiren. 'Development Oriented Theatre: Challenges and Prospects.' Natak Budreti: Introspecting 150 years of Gujarati theatre, 130–134. Ahmedabad, 2007.

Joshi, Umashankar. Saapna Bhara. Ahmedabad: Gurjar Prakashan, 1936.

Mangalam, Harish. Gujarati Dalit Ekankiyaan. Ghaziabaad: Sahitya Sansthaan, 2011.

———. ‘Sacchai ni Najare’. In Gujarati Dalit Sahitya ni kedie, edited by Dalpat Chauhan. Ahmedabad: Gurjar Prakashan, 2015.

———, ed. Hayati. Ahmedabad: Gujarati Dalit Sahitya Academy, 2002.

Parmar, Mohan. Bahishkar. Ahmedabad: Rannade Prakashan, 2004.

Parmar, Krishnachandra. Tipe Tipe Shonit Aapya, 1986. Ahmedabad.

Verma, Shrikant. Triveni Sangam. Ahmedabad, 1977.

Yashaschandra, Sitanshu. ‘Rang Che’—An Anthology of Post-Independence Gujarati Plays. New Delhi: National Book Trust, 2010.