Of one of the strangest places for a craft to be revived, the Jaipur Central jail played a key part in the revival and protection of the art of hand-woven carpets. A Mughal import into India, colonial influence over the Indian subcontinent by the 1850s had shrunk traditional crafts like carpet weaving until it was introduced as a prisoner reform programme by the Maharaja of Jaipur, Sawai Ram Singh II. We trace the journey of these carpets and dhurries that now occupy place of pride across world museums. (Photo courtesy: Wikimedia Commons)

On October 1, 1894, one of the largest Indian carpets on record arrived in Chippenham, bound for the Waterloo Gallery in Windsor Castle. The Clerk of Accounts, A.G. Seymour, recorded in his diary:

On that October morning word was brought that at the G.W. Railway Station, they had for delivery an immense roll of carpet, and would we send down to determine how it could be delivered. It was found stretched across two railway trucks. It was a really gigantic roll, bound in long timber splints and weighing several tons. The firm who did our carriage, for there were no motors in those days, volunteered to tackle the job and we sent forty men to help. The great thing straddled over two lorries drawn by four horses and the men pulled with ropes, and so they started up the Castle Hill. It was a sight worth seeing, men and horses straining their utmost amid the shouts of those directing the operations.[1]

In mid-nineteenth century India, Indo-Persian pile carpets like this one—symbols of wealth and exoticism—were woven not in ordinary craft workshops, but in jails! While this carpet was commissioned from the Agra Jail, it was in Jaipur where carpet weaving began as a large-scale jail industry. A Mughal import into India, growing colonial influence over the Indian subcontinent by the 1850s had shrunk traditional crafts like carpet weaving until it was introduced as a prisoner reform programme by the Maharaja of Jaipur, Sawai Ram Singh II.[2] He founded and built the Jaipur Central Jail in 1854. ‘Jail carpet’ weaving began here, spreading across Rajasthan into jails in Ajmer and Bikaner.

Also read | Kalamkari: Textile Tradition of Andhra Pradesh

Reflecting the larger trend towards jail reform at the time, carpet weaving was used to counteract increasing costs, while providing better control of the prison population. Colloquially known as ‘convict or jail carpets’, they were also an unlikely form of craft revival following their popularity at colonial exhibitions such as the London Great Exhibition of 1851.[3]

From Jaipur to the World

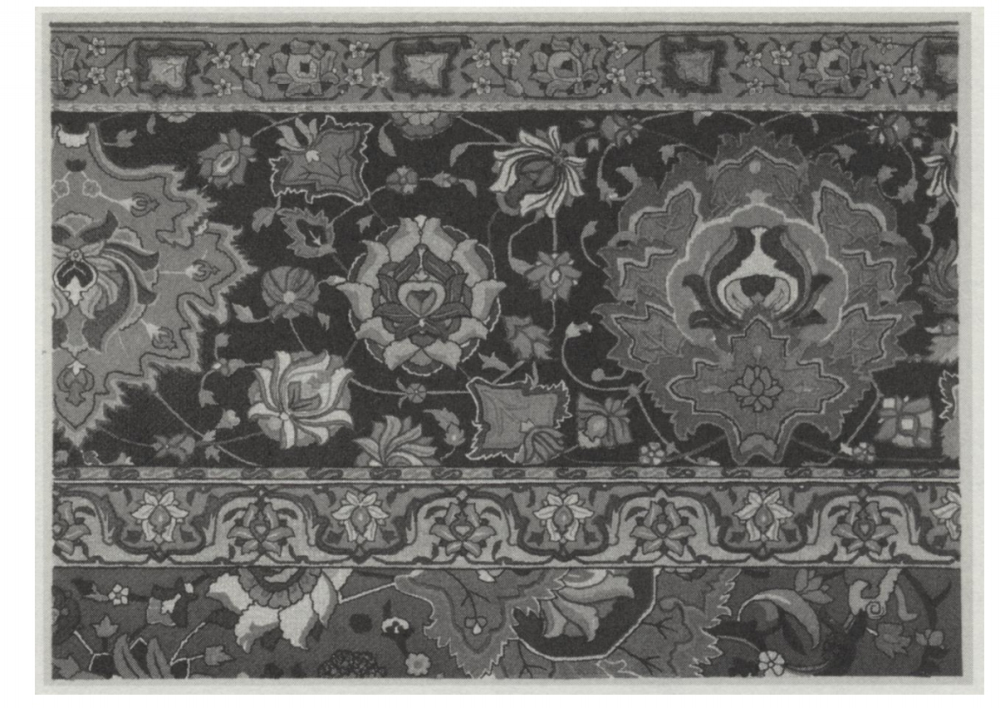

Handwoven on large looms, the carpets were created using a series of knots. They featured designs taken from historic collections, particularly inspired by the maharaja’s collection. Popular designs were replicated, and copies of these patterns were shared among the jails across Jaipur, Bikaner, Agra, etc., making it difficult for auctioneers today to identify their origin. The practice was then adopted by the British in jails across the United Provinces, the Punjab, Gujarat, Maharashtra, and even as far as Mysore.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, carpet patterns began to be published in monographs, making copying even easier. Water colour designs from one such monograph, published in 1905, under tutelage of British architect Sir Swinton Jacob by his students, are now in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. These designs feature border motifs and other intricate details of the carpets, which could then be copied by anyone.[4]

Though jail carpets did not elicit the profits some colonial officials had hoped for—largely due to the ever-shifting prison population—their benefits included disciplining the prisoners through craft, subsidising incarceration with the sale of products, influencing product design, and creating a modern industry based on traditional design principles.[5] The carpets themselves were coveted and had important clientele; in 1928 and 1929, the Jaipur Jail received commissions for carpets from the Viceregal Lodge in Simla, and the Viceroys House in Delhi.[6]

Also read | Sambalpuri Textiles: Art and Artists

Carpets frequently travelled internationally as gifts, a practice which continued well into the twentieth century. One such carpet was found at the Polesden Lacey, an Edwardian House and Estate in the UK.[7] It is thought that the maharaja of Jaipur and Agra, Sir Jagatjit Singh Sahib Bahadur (1872–1949), gave this carpet to his host, Mrs Greville, during a visit to the estate between 1935 and 1937.[8] Carpets such as this, therefore, represent cross-cultural relationships as they were a material object equally prized in India and Britain, symbolic of wealth and status.

Today, these jail carpets are considered collectibles, sold at auction for large numbers, coveted by museums, and represent an important part of the Indian textile industry.

The Modest Dhurrie

However, not all of the carpets woven in Rajasthani jails were of the silk hand-knotted Mughal-Persian-style; some were woven cotton dhurries, representing a different form of floor covering native to Rajasthan. It is perhaps these simpler dhurries that Lockwood Kipling, father of Rudyard and the first principal of Lahore’s Mayo College of Arts, described as ‘an equal and formless sprinkling of somewhat hot colour all over the field’.[9] Some of these jail dhurries are on view online.[10] Similar to the silk pile carpets, dhurrie patterns were replicated in jails throughout Rajasthan, with some examples surviving till date and still stocked by carpet sellers in north India, says Dhruv Chandra, owner of the Carpet Cellar.

However, many convicts did not continue the craft after their release as they regarded making carpet a punishment, rather than a vocation, says historian Abigail McGowan.[11]

After Independence

At Jaipur Central Jail, carpet weaving continued beyond Independence. The 1961 Survey of Selected Crafts notes that 35 men were employed in the jail. Of the 18 looms there, just five were unused.[12] The census further notes that ‘some of the big looms are lying idle due to lack of orders for big carpets.’[13] These looms were left over from the colonial era, when they were a competitive advantage, enabling certain jails to weave very large opulent pieces, such as the carpet installed in the Waterloo Gallery at Windsor Castle.[14]

Today, antique jail carpets are still being discovered. They are coveted at auctions and by museums, fetching huge prices. Each has a story to tell—of the weaver in jail forced to participate in an industry they may otherwise have avoided, of the impact of Western demand on Indian crafts, and of modernisation on traditional practices. In recent years, the company Jaipur Rugs has embarked on a ‘carpet weaving for reform project’ in Dausa, Bikaner and Jaipur Central jails, producing a Freedom Manchaha collection of carpets made by inmates.[15] A news report says that such carpets almost fetches $40 per square feet in Europe. Unlike during the colonial era, the inmates today have a choice of whether they want to participate and design their own carpets.[16]

From luxurious pile carpets to the more modest cotton dhurrie, Indian floor coverings remain an important and world-renowned part of the Indian textile industry. Beyond the traditional weaving communities, it is the inmates of Rajasthani prisons that have been instrumental in retaining the knowledge, skills, and traditions necessary for weaving to continue, two centuries after the maharaja of Jaipur began the first jail carpet factory in Jaipur.

This content has been created as part of a project partnered with Royal Rajasthan Foundation, the social impact arm of Rajasthan Royals, to document the cultural heritage of the state of Rajasthan.

This article was also published on Livemint.com.

Notes

[1] ‘Indian - Carpet,' Royal Collection Trust, accessed January 22, 2011, https://www.rct.uk/collection/35837/carpet.

[2] ‘Flat Woven Rugs of India: Past-Continuous - Jaipur Virasat Foundation,’ Google Arts & Culture, accessed January 19, 2021, https://artsandculture.google.com/exhibit/flat-woven-rugs-of-india-past-continuous/KAJSlmbixCYTKA.

[3] Abigail McGowan, ‘Convict Carpets: Jails and the Revival of Historic Carpet Design in Colonial India’, The Journal of Asian Studies, 72.2 (2013): 391–416, January 19, 2021, https://www.jstor.org/stable/43553183.

[4] ‘Design,' V&A Collections, accessed January 22, 2021, http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O403887.

[5] Antonia Behan, ‘Jail Carpet,’ John Lockwood Kipling: Arts & Crafts in the Punjab and London, accessed January 31, 2021, www.bgc.bard.edu/research-forum/articles/242/jail-carpet.

[6] Shyam Ahuja, Meera Ahuja, and Mridula Maluste, Dhurrie: Flatwoven Rugs of India (Mumbai: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2000) , 65.

[7] ‘The Maharaja’s Gift,’ National Trust, 2016, accessed January 23, 2021, https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/polesden-lacey/features/the-maharajas-gift-march-28-2016.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Kirstin Gotway, ‘John Lockwood Kipling: Arts and Crafts in the Punjab and London by Julius Bryant, Susan Weber, et al.,’ Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide, 18.2 (2019), accessed February 22, 2021, https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2019.18.2.12.

[10] ‘Jaipur Jail Dhurrie - Sample 11,' Google Arts & Culture, accessed January 23, 2021, https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/jaipur-jail-dhurrie-sample-11/qgGCU12wTRPs_w.

[11] Abigail McGowan, ‘Convict Carpets: Jails and the Revival of Historic Carpet Design in Colonial India’, The Journal of Asian Studies, 72.2 (2013): 391–416, January 19, 2021, https://www.jstor.org/stable/43553183.

[12] C. S. Gupta, ‘Survey of Selected Crafts, Part XIV, Vol-XIV, Rajasthan,’ Census Library, India, 2016, accessed January 24, 2021, http://localhost:8081/xmlui/handle/123456789/2289.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Partha Mitter and Naman P. Ahuja, eds., The Arts and Interiors of Rashtrapati Bhavan: Lutyens and Beyond (New Delhi : Publications Division, Government of India, 2016), accessed January 23, 2021, 286, http://archive.org/details/artsinteriorsofr0000unse.

[15] ‘Freedom Manchaha- Handwoven Rugs of Hope,’ Jaipur Rugs, January 31, 2021, https://www.jaipurrugs.com/shop/freedom-manchaha?ref_origin=Topnav.

[16] Keerti Kadam, ‘Freedom Manchaha, the Innovative Initiative by Jaipur Rugs and the Prison Department!,’ Cine Buster, January 26, 2021, accessed January 31, 2021, https://www.cinebuster.in/freedom-manchaha-the-innovative-initiative-by-jaipur-rugs-and-the-prison-department/.