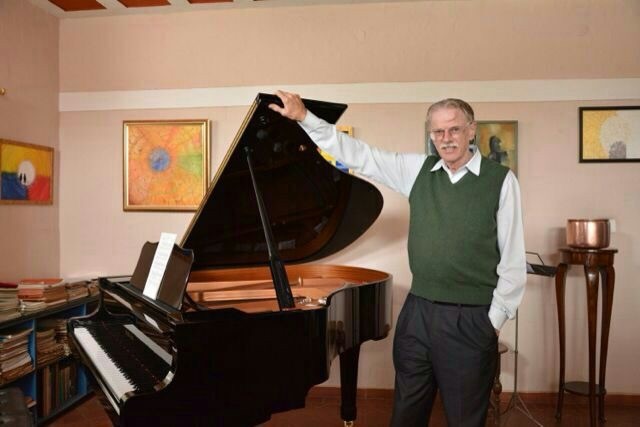

Fig. 1: Jan Brouwer

Dr Jan Brouwer is a pioneer in the field of the anthropology of artisans in India. A versatile personality of several accomplishments, he lives and works in the quiet confines of Mysuru, South India. Author of The Makers of the World (1995) and Coping with Dependence (1988), he recently donated his personal archive on Visvakarmas in Karnataka to the Southern Regional Centre (SRC) of the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts (IGNCA), Bengaluru. Dr Sreekala Sivasankaran, Associate Professor and Project Director of ‘The Worldview of Visvakarmas’ project at IGNCA, New Delhi, makes a vignette of the man and his work in this conversation with Dr Brouwer (conducted on October 11, 2016).

Photo Courtesy: Jan Brouwer and SRC, Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, Bengaluru

From Amsterdam to Mysuru

Sreekala Sivasankaran: Jan, you are an anthropologist who travels between continents, a pianist and a biker. How did you come to study the Visvakarmas of India?

Jan Brouwer: Since childhood, I have always been interested in the material world. At six, my father taught me basics of architecture and, as children often do, soon I attempted to design residential buildings and even produced (to scale 1:100 cm), a model town of cardboard. I remember this always as I am sitting at the same desk today. I was born and brought up in Amsterdam, although most weekends I spent with my grandparents who lived between a beach and a forest, 45 km west of Amsterdam.

From architecture, my interest went to interiors and furniture. A few years later, I wanted to put my interest into practice and tried my hand on producing a few (wooden) cabinets for relatives. After completing these (TV) cabinets my interest moved to broadcasting. In school I had a friend who made an FM transmitter and I produced programmes. The range was only 1 km but it was fun. I considered myself a broadcaster of sorts. Later I joined one of the national youth radio stations (AVRO Minjon) and through them I came into touch with a hospital whose social department was setting up hospital broadcasting service to cater to the needs of the patients of this 600-bedded St Lucas hospital. On their request I helped the station to draft their Constitution and Byelaws and the station started working soon after. I produced and presented one programme a week for five years.

Between age six and nine I had piano classes from Lisbeth de Waal in Amsterdam. In 1957 I played Kuhlau’s Sonatina Opus 20 at the Minerva Pavilion for an audience of 300 and the question arose should I continue in music. The answer came fast: I failed in school, thus music was out: studies! Years later, in Mysuru, I took up piano playing again and got an opportunity to play piano in a four-star hotel in Mysuru.

Later, guided by one of my batch mates, late Bert van den Hoek, I moved to Leiden and when he asked what my plans were for the summer holidays. I said, ‘no plans as yet’. His reply was, ‘Well, why not join me on a hitch-hike trip to India?’ This was in 1970 and we spent three months in the subcontinent. On my return, I decided to read a course in the ‘Anthropology of India’ by Prof. Jan C. Heesterman. I learned that the artisans and craftsmen had never been studied as a separate subject from the anthropological point of view and then, when passing the window of the Bijenkorf, a department store in Amsterdam, I noticed handicrafts from India and my interest was aroused. I went inside and asked to meet the manager with the question: who made these handicrafts, where do they come from? Not satisfied with the answer I decided to return to India and find out myself.

From Leiden via Delhi to Mysuru

S.S.: And, you returned to India in the mid-'70s. How did your search take you to South India and to Mysuru in particular?

J.B.:Yes. My first visit to India was without academic interest. I came as a backpack tourist on a budget of one dollar a day in 1970. Having completed a theoretical BA thesis on South Indian temples in which I argued that temples are economic centres where redistribution of wealth takes place through the third element of the deity, I returned for fieldwork to India for my MA thesis in 1975. At the end of this fieldwork, I was gracefully received by Mrs Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, at her residence in New Delhi on April 9, 1976. She presented me her book Handicrafts of India (1975) with the wish that I would continue my research.

In 1978, I returned again to India for fieldwork for my PhD thesis. Except in 1986, I have been in India all these years. The greatest surprise was on the occasion of my passing the PhD defense. The Ambassador of India to the Netherlands, Mr K. Srinivasan, presented me with exquisite reproductions of Tagore paintings and if that was not enough, a telegram from Dr Kapila Vatsyayan, Member-Secretary IGNCA, inviting me to conduct research on the blacksmith. This telegram marked the beginning of fresh research. Simultaneously, I was project director on an Indo-Dutch project (IDPAD) and thereafter Dr D.P. Pattanayak urged me to set up a research centre (CARIKS) in Mysuru.

In the same period I continued to write papers and articles on anthropology, most of them on the artisans of Karnataka and, in 2001, I was interviewed by the UGC for the post of Professor of Anthropology at NEHU, Shillong. When I returned to Mysuru in 2005, I took up translation and language training on the request of various companies. Altogether, I have been in India for 38 years and although I never migrated, I am still here.

Originally, I had planned to study the crafts in north India for my MA thesis. So, in 1975, I started library research in Delhi and lived in Defence Colony as a paying guest. I wanted to test myself as a fieldworker and had seen so many woodcrafts from Kashmir in Delhi that I flew to Srinagar to test myself in what was then known as a ‘difficult field area’. The university in Srinagar helped me with accommodation and provided a research assistant. For one month we interviewed carpenters and weavers. At that time, I had no idea about the Visvakarmas. After one month, I had to fly back to Delhi and had to take the bus to the airport. As I was early and the bus was late, a conversation developed with another foreigner waiting for the bus. He was an American scholar and I regret that we never introduced ourselves to each other. I have never known who he was. We talked about my intention to study Indian crafts. It was this unknown American who suggested I go to Mysuru as there are many living crafts in that region and also that I meet Dr P.K. Misra of the Anthropological Survey of India in Mysuru. Had the bus not been delayed I would never have got this information! So, let us not always complain about delayed buses!

Back in Delhi, I went to the Ratan Tata Library and checked in the Who is Who in India volume who P.K. Misra was. And indeed, the information was correct. Subsequently, I took the Grand Trunk Express to Bangalore and Mysuru and I remember very well that I entered the ASI office at exactly 1:55 pm and met Misra. (At 2:00 pm the office would close for lunch). This was an inspiring meeting. He said: ‘Time to undertake such a study is now or perhaps never.’ At that moment it became clear that I had to study the craftsmen of Karnataka. As it had to be a limited study at MA level, I restricted the study to sandalwood and rosewood carvers of one urban region (Mysuru) and one rural region (Shimoga District).

Mysuru was a fairly large kingdom with royal patronage to artisans while the last Maharaja was the first Governor so that the social economic networks remained intact also after Independence. This impact came out in my later study comparing Smiths and Weavers in Mysuru District (Old Kingdom) and Bijapur District (previously part of the Bombay Presidency).

Coming from the Netherlands, in Mysuru, I conducted most of my fieldwork on bicycle. In Sagar (Shimoga district) I hired a bicycle to visit a Blacksmith 30 km from town. There and then I found this too tiring—the country is not as flat as the Netherlands—and in case I had to return, I would do so on a motorcycle.

Does serendipity exist?

S.S.:This is interesting…one thing leading to another...serendipitous meetings changing the course of journeys...Was there any moment when you felt blocked and halted?

J.B.: If one looks back one can see many chains of meetings that all began with one serendipitous meeting. ‘If I had not met that one person I would never have met you’ kind of thing. Some chains are pretty long; others are shorter but not less important.

I cannot remember that I ever felt blocked or halted but I always have contingency plans. In my view, it seems always best to take every difficulty as a challenge. Take a deep breath, counting your blessings, empty the mind and restart. I remember two instances.

On the very first day of my first fieldwork in New Delhi in August 1975, I carried two introductions: one from the University of Leiden and the other from the National Museum of Ethnology in Leiden. When I wanted to meet these two people, I found that one had moved to Kolkata and the other had passed away. So there I was, alone in Delhi. What to do? I took a telephone directory and looked up Handicrafts. I found the All India Handicraft Board and the department at the Ministry of Culture. I wrote my own letters of introduction and decided to hand them over in person. Handing them over in person was not easy as one had to pass an army of Personal Assistants to reach the top guy. Endurance pays in the end. I introduced myself to Ms Pupal Jayakar who received me with warmth and affection and without whom I would never have been able to start my work. In the Ministry I met Mrs Sita Kirpal who received me equally well and helped me a lot. Through her I met her brother, the poet Prem Kirpal, with whom I had long conversations from which I learned so much.

In Karnataka, I remember only one serious difficulty in my fieldwork in a village outside Hubli. Suddenly nobody would co-operate. It puzzled me. This had to be solved as it was an important multi-caste village. So I decided to bid farewell (without having conducted any interview) and expressed the hope to return. This was a difficult decision but the right one. Two months later I returned and was received well and could complete my work. On reflection I realized that I had become the playball of two factions on the one hand and I had not recognized the two centres that really matter: the richest man and the most religious man of the place. The rich man upon whom the Blacksmiths and Carpenters depend should give his ‘permission’ for me to do fieldwork but for the others this is not enough. The most religious man should give his blessing too! Both these men challenged me by inviting me for lunch at the same time on the same day. So I had to invoke Nature and my physician and had an early rice lunch with the rich man and a late chapatti lunch with the religious man. Retrospectively they are conceptually the King and the Brahman of the village.

Further inspirations and challenges

S.S.: Fieldwork Anthropologists would agree that everything that happens in the field is important. Interestingly in your case, you chose to settle down in the field eventually. We will come back to it later. As you started your anthropological field research in Karnataka, what were the existing material and writings that guided you or you found significantly motivating?

J.B.: The most interesting books to read and that I still value much for my on-going studies were A.L. Basham, The Wonder that Was India. I never understood why Basham used the past tense. Is India not a wonder still? Bernard Cohn’s An Anthropology of India, which is a 90-page thin book but still the most useful introduction to the sub-continent. The Modernity of Tradition by the Rudolphs remains a classic. And a most penetrating article by Heesterman, 'The Conundrum of the King’s Authority', which reflects his original thesis on the coronation ceremony of the king. Regarding Karnataka, Nilakanta Sastri’s book, A History of South India and the old gazetteers and of course Thurston’s volumes on castes were curiosity-provoking titles.

S.S.: What were the challenges and potentialities of studying the South Indian situation as ‘outsider’? The ‘outsider’ term may sound rather inappropriate when one looks at your work and life in India over the years. However, in anthropological practice, the inside/outside dynamics is very much part of the methodology and a vantage point from where one moves on creatively.

J.B.: Oh dear, yes, the ‘outsider’ issue is still very much alive. Or rather, I name it the ‘us’–‘not us’ issue now. Of course, it played and continues to play a role. It is part of the cultural system logic and thus it is a matter as to how one is coping with it. At that time (1975) many anthropologists ‘went native’ to cope with their ‘culture shock’. I found that nonsense but it fell in line with the current hippie trend after the Beatles’ visit to their guru in India. I thought how would I respond to an anthropologist who came to interview me about my family, work and life in the Netherlands? On second thought I found this question wrong, as it has the hidden assumption of the modern state.

What we do have is two individuals and thus the question is one of trust and reliability. Be true to yourself is the answer. So I continued to wear western dress and footwear. I made it clear that I am Dutch and had been engaged in simple carpentry myself and wanted to know how these crafts are being done here. So, my first fieldwork was about woodcraft and carpentry. In the course of that fieldwork I came to know about the composite caste of Visvakarmas and others who were also engaged in these crafts but were not classified as Visvakarma. This information in the context of one year of study of Sanskrit (I dropped out there) led to the following initial question: where everything in flora and fauna is classified (in the texts) then all people and especially the artisans should also be classified. This was an issue to be sorted out.

Fieldwork

S.S.: In your personal archives, there are very interesting photographs from the '70s. Say, for example, there is a picture of you immersed in work in a Goldsmith’s workshop and in another picture, you are surrounded by an adoring crowd as if you’re a neta (official) or a bridegroom. In yet another newspaper clipping, you were referred to as Dr Jan Brouwer alias Chandrachudachar. It seems obvious that the local community in Karnataka had embraced you with enthusiasm. How was the experience for you? What skills have you picked up from your stay in India?

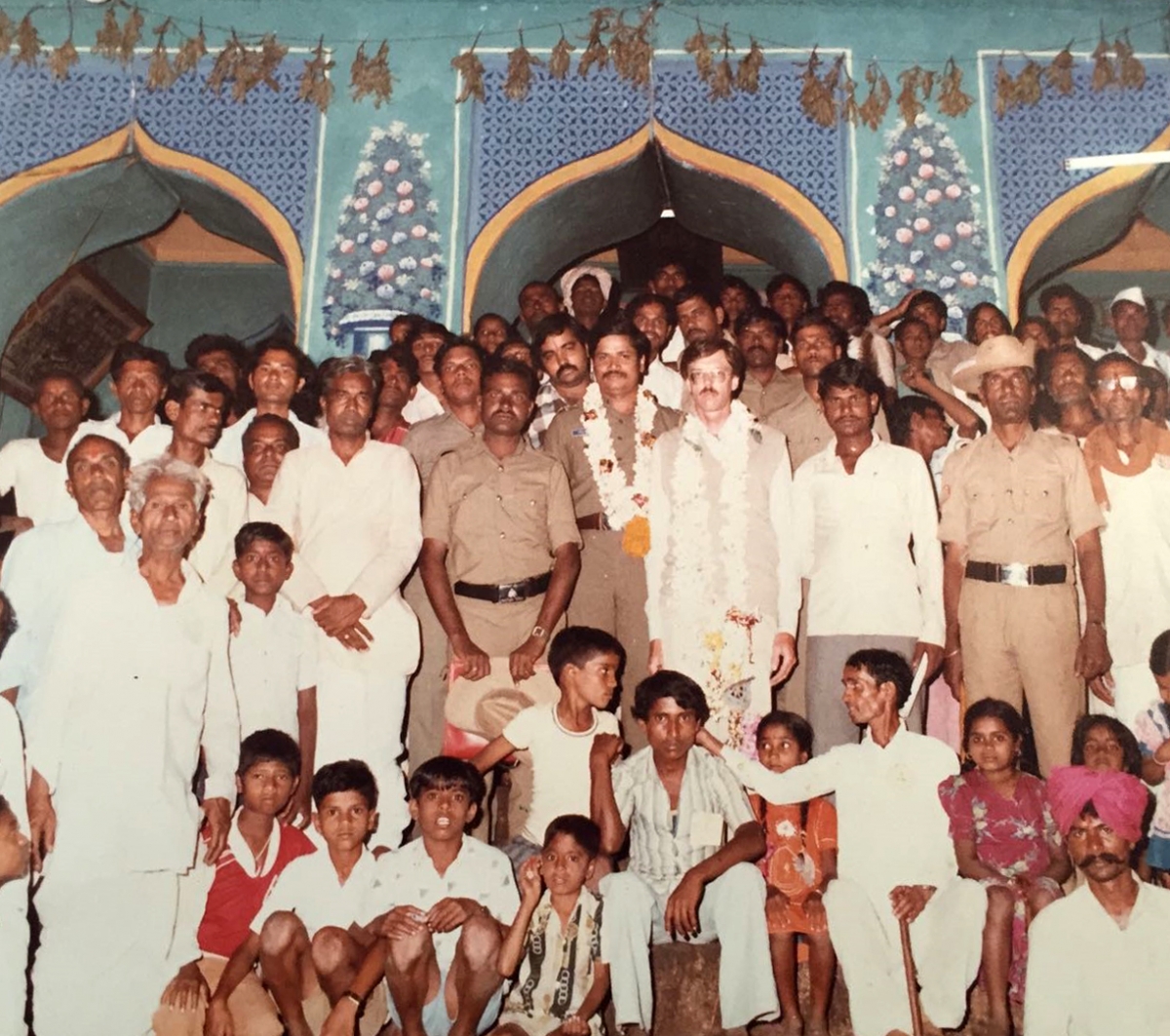

Fig. 2: Jan Brouwer at Munishvara Jatre in Tintani,Gulbarga District, Karnataka

J.B. :When I came to India, I had already a few experiences with carpentry. My engagement in the crafts was participant observation to get the feel and information from inside. I failed miserably as a Goldsmith. But I learned a lot about ‘goldsmithy’ including the secret crafts lexicon!

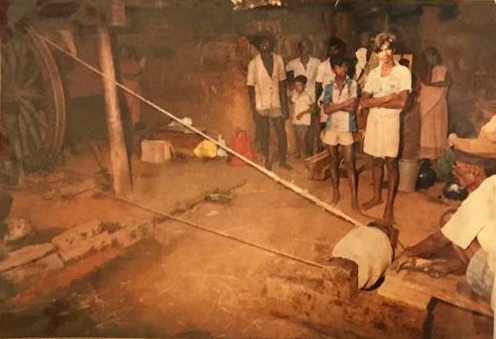

S.S.: What are the distinct features of carpentry you observed in India?

J.B. :The most striking difference between Dutch and Indian Carpenters is the number of tools they use. The village Carpenter works with a minimum number of tools, most of which he used to make himself with the help of a Blacksmith. Secondly, preparation of a work in India is complete oral tradition. Virtually never any design is drawn on paper or in sand first.Having said that, a carpenter from Europe will understand a carpenter from India as far as the techniques are concerned.

Outing to architecture

S.S.: You have brought from Amsterdam exquisite Dutch furniture for your home in Mysuru…

J.B.: I brought things dear to me as I settled down here. I designed the house to fit my heirlooms and piano. If you’ve noticed, there are 64 windows for the 64 arts of Goddess Saraswati and octagon shape alternated with square middle floor resembling Purusha or left over of the original creation.

After I designed and built my house, I received assignments for other residences and new locality outlay. As said before there was no school of architecture in Mysuru, I got five Engineering students from National Institute of Engineering (NIE) as trainees. While I designed, they did the final drawings and assisted in site measurements.

Anthropology and History

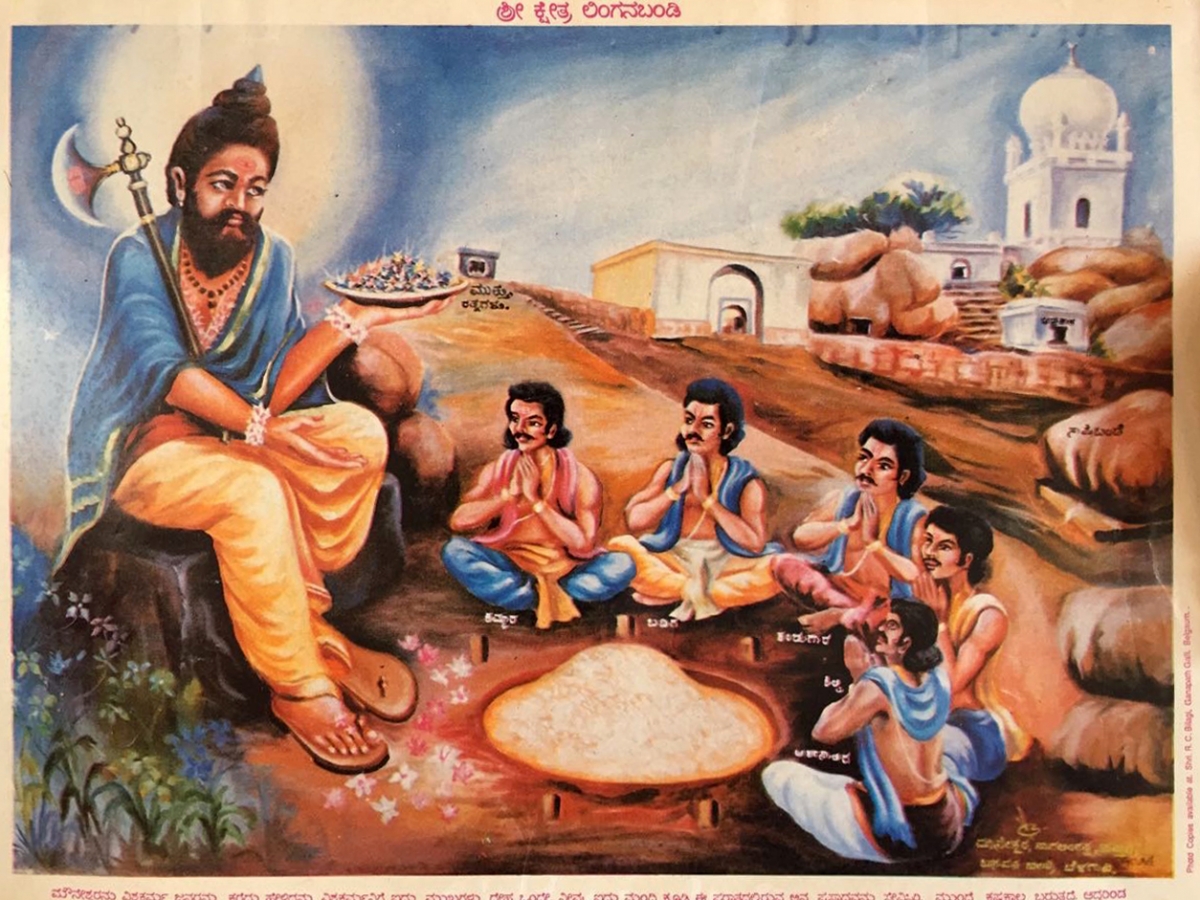

Fig. 3: Visvakarma Sculptor

S.S.: Visvakarmas are not a homogeneous entity, but a collective identity of five groups mainly. According to historian Vijaya Ramaswamy, the term Visvakarma began to appear in South Indian inscriptions referring to the smiths from the 12th century onwards. What is the basis of the usage of such an umbrella term for such diverse groups as the Blacksmiths, Carpenters, Coppersmiths, Sculptors and Goldsmiths who work on different metals, wood and stone and who worship various Hindu deities and not just Lord Visvakarma?

J.B.: At the outset, I wish to follow the indigenous Visvakarma sequence of the crafts as it is presented in their written and visual publications. This sequence is at once a craft technical and social order: Blacksmith, Carpenter, Coppersmith, Sculptor and Goldsmith. Stonemasons or Stonecutters were not included.

As for an early record of the usage of the term Visvakarma, there is an inscription on the Ganga copperplate from Thanjavur, dated 247 A.D, on which the engraver is mentioned as ‘Visvakaarm Acharya’. This was a reference to an individual. Today, the term Visvakarma refers to the caste as a whole.

Homogeneity and umbrella are modern ideas that belong to the Modern State. In contrast to, I dare say, the rest of the world, Hindu culture does not replace existing ideas, categories or substances by new ones but adds new ones to the existing ones. Thus, the Modern State became juxtaposed to the Scriptural Tradition and the Traditional Practices. I have argued that with the emerging IT sector a fourth tradition is being added: the Simulation State (a term I borrow from Baudrillard).

In my work, I have constantly been aware of the tricky relationship between anthropology and history. Usually anthropologists tend to see structures where they do not exist. One has to make it very clear whether all field data belong to the same historical layer. Once a structure is found it has to be tested in another region. This is what I did in The Makers of the World (1995). It shows the structure of the caste in three regional variations. This has two major consequences. First, the structure is simple: there are inclusive sub-castes (Power) and exclusive sub-castes (Authority). On the conceptual level they are strictly separated and this frozen condition requires logically a third element to make the system work. In this case that element is the Goddess Kali. Secondly, it shows the importance of critical mass.

Once the structure is found, the second test is explaining changes. The linguist De Saussure and later Claude Levi-Strauss have drawn anthropologists’ attention to the relationship between structure and change. The structure remains the same but the elements of which it is composed may change. So, we see fusion and fission of sub-castes and cross-regional marriages as aspects of a total response to changes in the rest of society.

The System Logic

Fig. 4: Makers of the World (1995)

S.S.: In your work, Makers of the World , you talked about the Visvakarma ideal as (part of) the Brahmanical order. Can you briefly explain this?

J.B.: I agree with Heesterman that the essential segregation is the one between the transcendental order and the mundane world. The transcendental order is the order of moksha and this order is manifest in the world in which the true sannyasi is the representative of the transcendent order. The true world-renouncer is the only true brahman. As per the Visvakarma point of view, brahmans depend on them for puja tools and thus there is interdependency that is non-brahmanical.

Brahmans lose their transcendent authority when they vindicate the power of the king in the coronation ceremony. The real Brahman, as I said above, is only the sannyasi that is neither the certified Brahman nor the Visvakarma and in fact anyone can become a sannyasi, that is, one who stands with his back to the world.

In the transcendent order of moksha, God is in his own box, here ‘god is you’. It is the order of the ideal Brahman of which the sannyasi is the representative in the world. In the world, Power (King’s achieved position) and Authority (Brahman’s ascribed position) are segregated in principle. As such, this would make the world a clockwork Orange. Thus a third element is needed, a trickster if you like, to bend the rules and to deal with the unknown or uncontrolled ‘not us’. The gridlock has to be unlocked so as to say. This means negotiation at all levels at all times.

In the Hindu worldview, there is a split between the Transcendent and Mundane, and the same must be established in the world with Brahman, King and a third element, which may be a Goddess in various cultural or natural forms or a Guru. The critical difference is that the transcendent remains inert and unreachable.

Historically, the Visvakarmas have no point of reference in the indigenous sociological theory of varna categories. They responded by claiming either the Brahman or Kshatriya status. This response I see as one to an opportunity/threat from outside. For, in society they are not recognized as having a clear status. The others do not really know how to classify them and hence not how to behave with them. In many situations they are often avoided even in such modern institutions as universities.

Taking the caste as a whole, we thus see the concepts of Power (inclusive, Kingly) and Authority (exclusive, Brahmanical) in alignment within the caste. For all Visvakarmas the rallying point is their Goddess Kali. Let me illustrate this with the case of the Visvakarmas of southern Karnataka. Here the Visvakarma caste comprises four sub-castes, namely: Sivachar, Uttaradi, Kulachar and Matachar. The Sivachar and Uttaradi sub-castes substantiate the concept of Authority while the Kulachar and Matachar substantiate the concept of Power. The agreed internal ranking of these sub-castes from high to low is: Sivachar, Uttaradi, Kulachar and Matachar. On the Authority side, the Uttaradi rank lower as they deliver the priests to the Kali temples. On the Power side the Matachar rank lower as they are strongly market oriented.

Power and Authority are necessarily segregated and necessarily arbitrated. Segregated because either left to itself is chaos and freeze respectively, and arbitrated because the logic of each excludes the logic of the other while both are practically necessary.

The substance of Power is local and permeated with political manipulations, backroom politics. The substance Authority shows supra-local connections with acquaintance level connections. It creates confusion and complexity by bringing in an outside factor that it can negotiate but that no one else knows what to do with. It deconstructs a situation and that ability to deconstruct gives the right to choose what it will focus on out of an arbitrary list.

The role of the Goddess is social and economic. The Goddess is a storehouse of knowledge that could blow everything up if it were let out and played both sides of the game privately and turned up publicly on the side of the winners.

S.S.: What is the composition of the sub-castes Kulachar, Sivachar, Uttaradi and Matachar in terms of crafts?

J.B.: The Sivachar sub-caste comprises all five crafts; the Uttaradis are only Goldsmiths. These two sub-castes are vegetarian. The Kulachar sub-caste consists of Blacksmiths, Carpenters and Goldsmiths, while the Matachar sub-caste are only Coppersmiths. The latter two sub-castes are non-vegetarian.

S.S.:Would you also say that the Visvakarmas were coping with dependence within this order, even when their social realities were often characterized by marginalization on the basis of caste?

J.B.: In the contemporary situation we observe a re-organisation to cope with the modern opportunity/threat. There is differential response to modernity. The Kulachars increase their inclusiveness; the Matachars are rapidly leaving the crafts and enter into modern contract-based professions; the Sivachars adopt modern manufacturing techniques; the Uttaradis are leaving priesthood to take up modern occupations.

Concurrently, the various Visvakarma, often local, mathas have agreed on the formation of an apex body, one matha that oversees all these local ones. At the same time, the sub-castes are in the process of forming a political association to voice their problems vis-à-vis the Modern State. The image of Lord Visvakarma makes its entry into the Kali temples and is worshipped even now. Simultaneously there is a trend of genealogical integration of Kulachars and Matachars while the Uttaradis are intermarrying with a similar sub-caste of central Karnataka. The Sivachars remain as exclusive as they were.

Thus the issue is not marginalization. We have to view their situation from an indigenous point of view and then we see an indigenous coping mechanism, of coping with opportunity/threat from outside. The Visvakarmas have perceived their situation as such ab initio. The history of India is replete with examples of similar situations and responses and thus we can say that the Visvakarmas were the avant garde of the social system.

The importance of indigenous views

S.S.: Let us delve into the indigenous thinking that you refer to. You talked about the situation where everything in flora and fauna are classified and that the Visvakarmas have no clear point of reference in the varna categorization. Why this silence?

J.B.:Heesterman was the first to draw our attention to the unique Hindu separation between the transcendent order and the mundane world. The transcendent order of virtues. This order is manifest in the world in sannyasis and the original mathas. In these institutions that are isolated from the world (the sannyasi should go out begging for food when the smoke stops coming from the chimneys while the mathas are traditionally physically and mentally isolated from the world in which we live) the texts, first as oral tradition and later written down, find their origin. Thus, we may say that the texts are located outside the world. It is in these texts that we find elaborate classifications of flora and fauna. For example, the Shilpasastra is rich in such classification as well as in descriptions of rituals for craftsmen. But there is nothing about how craftsmen should actually work.

Let us look at the indigenous sociological theory of varna states four categories: Brahman, Kshatriya, Vaishnava and Shudra. These are points of reference for the substances (jatis) of Brahmans (priests), Kshatriyas (warriors), Vaishyas (traders) and Shudras (servants, workers). Nowhere the indigenous manufacturers i.e. the craftsmen are mentioned.

In my view, this absence is to be explained from the basics of the crafts. To obtain their principal raw materials—iron, wood, stone, gold—the Visvakarmas have to break into the Natural Order. This is a violent act for which there is no place in the texts (transcendent order).

S.S.: Have the metalsmiths, Blacksmiths and the Goldsmiths, ever engaged in the mining process, the carpenters in woodcutting and the sculptors in stonecutting in the quarries in the areas you studied?

J.B.: As far as I know, iron mining in Karnataka was only done by a small Visvakarma sub-caste, the Muddekammara of Bellari District. None of the other Visvakarma sub-castes in Karnataka today have a history of having been engaged in mining. The Visvakarma goldsmiths have never been engaged in mining. Long ago carpenters used to visit the forest to cut timber. In my books I have described the ritual of cutting wood as various carpenters told me. Sculptors still go to the quarry but would never cut the stone from the rocks themselves. These issues are aspects of coping with dependence.

Heesterman

S.S.: Can you tell a little more about your association with Prof. Heesterman? Have you discussed your work with him?

J.B.: My dialogue with Heesterman never ended. Each time I was in the Netherlands he invited me for lunch. During the last few years, we had lunch at the Faculty Club of the University of Leiden. These lasted usually three hours during which we discussed all things Indian and my work. Right from 1970 he has been my academic guide. We had fixed our next meeting in the first week of August (2014) in Leiden but shortly before he passed away. I continue to miss him.

Concepts and claims

S.S.: You talked about the Visvakarmas’ claim to the Brahman and Kshatriya statuses in some areas. In what specific ways, these claims were articulated? Did this happen in other parts of India and how did the Brahman and the Kshatriya castes respond to it?

J.B.:The claim to the Brahman status is dominant in Karnataka. Informants told me that in parts of coastal Andhra Pradesh few Visvakarma sub-castes claim the Kshatriya status. But it is never an either/or issue. Both claims occur in both regions. As I have shown in The Makers of the World, in each region of Karnataka, the caste as whole comprise two sets of sub-castes. The two vegetarian sub-castes represent conceptually the Brahman category while the other two sub-castes represent the Kshatriya category on the same level of abstraction. I am quite certain these claims are prevalent in Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and southern Maharashtra.

Those castes that are generally recognized as having the Kshatriya status simply ignore the Visvakarma claims. But the Brahmans – the ‘certified Brahmans’ so as to speak—refute the claim as they say one can only be a Brahman through descent. The problem is that most people argue naturally only on the empirical level and do not consider conceptual levels. Hence the local discussions are virtually never ending.

A case in point is the eye-opening ceremony of a temple idol, especially when it is concerned with a deity of supra-local stature. Both the Brahmans and the Visvakarmas (the sculptors) claim the right to open the eyes of the deity. It is only through this act that the idol comes ‘alive’. In quite a few cases I witnessed tough arguments that delayed the inauguration of the temple. At the end of the day, it is the chief sponsor of the temple who has to decide who has to the right to conduct the eye-opening ceremony.

This is really a classical case for two reasons. First, the traditional king’s duty is to distribute and control rights among his subjects. The king needs both the Brahman and the Visvakarma so he will opt for a compromise in which both touch the pupil of the idol’s eye but the Brahman touches it last and only through that act the deity becomes present. Secondly, it resembles the case of the coronation ceremony of the king. The king’s power has to be vindicated by the Brahman because of his transcendent authority. But the moment the Brahman enters into the service of the king (to vindicate his power) he loses that transcendent authority. The Brahman who opens the eye of the idol loses his authority at that moment. So, the Brahman who opens the eyes has at that moment the same status as the Visvakarma because the act makes him lose the authority that the Visvakarmas do not have. And this supports the Visvakarma claim.

The idea of the number five

S.S.: What is the basis of the five-fold point of reference by the Visvakarmas, as referred by the terms Panchalar, Panchanamuvaru or Ainkudi Kammalar in Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh and Kerala respectively. When there are so many other communities of craftspeople in India, why the Visvakarmas emphasize on five? Clearly craft activity is not the criterion but a specific understanding of it, a certain worldview that connects the five groups?

J.B.: The fact that just these five crafts have come together is based on their principal raw materials and the way they are obtained which makes the Visvakarmas different from the weavers, potters, cane workers and other craftsmen. So it is not a random number.

Interestingly, we know that there is the typical Asian number game: even versus uneven which you can see also in South-East Asia, e.g. in the kingdom of Negrisembilan and on Sumatra.

In India, I think, there is an interpretation of numbers so that it relates to an entirely different issue, namely, the idea of completeness. Completeness is perfection and perfection is a virtue that is located in the transcendent order and for which there is no place in the mundane world.

Certain texts, written as well as oral tradition, say that a temple should never be completed! In oral tradition, we also see that Chaturvedis have a problem and not the Trivedis. The number four indicates completeness, a closed universe, not of the world.

S.S.: In The Makers of the World, you have observed unity of caste and disunity of sub-castes in the case of Visvakarmas and you summarized the phenomenon through Bach’s Cantata no.207.

J.B. Bach’s Cantata is about ‘united discord of changing strings’. In our context this may refer to the variety of sub-castes. Over time sub-castes split or merge yet remain under the common umbrella of the Visvakarma caste. Bach’s music is known for its various counterpoints or concurrent melodies yet within an overall theme. The musical harmony and the rhythm unite the counterpoints as much as the Lord Visvakarma and the Goddess Kali unites the sub-castes.

Tools and product

S.S.: The devotion of the craftsman to his tools was well captured in the cover image of The Makers of the World. What was the Smiths’ and Carpenters’ attitude to their final product? In the case of Sculptors, we have seen them traditionally occupying a space and role up to the eye-opening ceremony.

J.B.: All Visvakarma craftsmen but for the Blacksmith deliver their finished product with a delivery puja. These pujas are described in detail in my book, The Makers of the World. One of the reasons for the puja is to take ‘violence’ out of the product so that the buyer can safely use it. The Blacksmith cannot do this puja for both iron and the Blacksmith himself are manifestations of Kali. This explains at once why the ayudhapuja is to be done by all people once a year.

Migrations

S.S.: Tungabhadra River is a natural frontier, also a dividing line between kingdoms and populations in the region. You have referred to a regional dimension or pattern in the case of the Visvakarma population distribution in Karnataka. Can you explain?

J.B.: The Tungabhadra is much more than a natural frontier. It is also an isogloss of the Kannada language. Before modern bridges existed, the Visvakarma sub-castes to the north of this river rarely if ever crossed the Tungabhadra. The same holds for the Visvakarma to the south of the river. During the past 30 years we still do not see inter-sub-caste marriages between the Visvakarmas of the north and south bank. Rather we see fusion of their sub-castes of the central and southern region, both to the south of the Tungabhadra River.

S.S.: Are there instances of migration or movement of Visvakarmas in the South as a group in search of raw materials or other aspects related to work, traditionally speaking, say for instance, like the Gadulia Lohars?

J.B. The issue of historical migration of artisans especially of blacksmiths has yet to be undertaken. I was thinking of the pioneering work of two scholars: on wootz in Andhra Pradesh by Thelma Lowe and on the Gadulia Lohar’s nomadic lifestyles by P.K Misra. In this context, the Visvakarma secret crafts lexicon may be another resource. At the outside, I feel, if we look at the five crafts the goldsmiths and a section of carpenters were traditionally travelling often in search of patrons.

Relevance of Oral Tradition

S.S.: You talked about the tricky relationship of history and anthropology, yet you advocate strongly for its alliance and also the need for comparisons. In a conventional sense, historians do not subscribe to oral traditions and anthropologists are often preoccupied with the ethnographic present. Then, there are self-perceptions by the communities. One could argue that none exists in a neutral, value free vantage point. Can you elaborate a bit more about the possibility of combining anthropology and history with reference to the study of Visvakarmas? What are the major sources of data that we are talking about in the specific case of Visvakarmas?

J.B.: A neutral, value free vantage point, I think can be approached but never completely achieved. Moreover, mankind’s only method is the comparative method. The approach can be worked on by first an awareness of one’s own cultural focus. The lens through which we see if not trained. The next step is achieving a more than basic understanding of the culture in which one is brought up. Understanding one’s own culture will then be the base to study another culture and identify the focus there. In my student days I made a humble beginning with understanding Dutch culture through an analysis of the Dutch main festival: St Nicholas celebrated for nine days and culminating on the saint’s birthday on December 6. I am still hoping that there is a student who will take up a comparative study of this festival in the Netherlands and the Dasara festival in Mysore as I feel there are structural similarities. Such festivals are (or were) known throughout the Indo-European linguistic region.

I think it is legitimate to use both universal categories and culture specific categories to analyze data. But all the time one must be alert on the cultural focus.

The synchronic nature of anthropology is its major risk. Most anthropologists are very keen to discover structures. Often they see structures where they do not exist because not all data belong to the same historical layer. This problem occurred on at least two occasions in my fieldwork, namely, when trying to find the meaning of a particular Kali temple and secondly, the meaning of the location and layout of a Blacksmith’s workshop. In both cases, the knowledge of the local oral tradition was of prime importance.

This tradition is also replete with historical fragments seen through the lens of the participants. It is not uncommon that the anthropologist features in new variations of certain oral tradition. It seems that I also feature somewhere but I have forgotten where that happened.

Most Visvakarmas of southern India, quote the 19th century Chittoor Court case to proof their Brahmanical status. The case features in the oral tradition as well as in the Court records! To understand the case I think it is of prime importance to realize that in India juxtaposition and not replacement is one of its main principles. The Scriptural Tradition and the Traditional Practices are juxtaposed to the Modern State. The latter has not replaced these earlier traditions. So, the status claim is a problem of the earlier traditions. This case was taken up by an institution of the Modern State: the Law Court. The paradigm of the earlier traditions and that of the Modern State are diametrically opposed to one another apart from being juxtaposed.

The major primary sources of data are oral tradition (all narratives including so-called 'bazaar prints'), historical records, the early travelogues and monographs.

S.S. I guess, the ambiguity in the traditional classification regarding the Visvakarmas, the intertwining statuses in certain ritual functions such as the eye-opening ceremony, which you mentioned all leave scope for interpretations. In the Chittoor zilla adalat arguments (1818), which were centred on the purity of origin and the right to conduct priestly functions, the Visvakarmas were reported to have convinced the court by citing vedas and puranas and by invoking their lineage to the five-faced Visvabrahma, their claim to conduct priestly functions as legitimate. The Visvakarmas here sought to re-claim ‘original’ identity while rendering the Brahman defendants as one of mixed lineage. As the power of the king waned and modern institutions took over, communities acquired a new agency for articulating or re-constructing their identity. Should the anthropologist be preoccupied with ‘earlier’ traditions or should they be examining the social world in its flux and change? When you rightly insist on understanding the indigenous thinking, the question remains whether we can do that by treating it as an insulated entity that can only be juxtaposed with other ways of thinking and not as something in interaction and transformation?

J.B. Throughout history of the Indian and Western world, identity has been a problem. When under impact of technological innovations, the relationship between the collective and the individual is being challenged, established identities are questioned and new identities are formulated.

The Law Courts are institutions of the Modern State. The Modern State is based on a certain set of principles. For example, it has the monopoly of the use of violence and of taxation for which it needs to classify both land and people. Thus, power, authority and means are concentrated in the Modern State, which tries to be independent of society. Politics and the political system are seen as a separate domain of activity. In the traditional order, the State is not concentrated but diffused. The Modern State being juxtaposed to the traditional order, and being a central authority with only central collection of taxes in the capital has to cooperate with local or regional rulers with diverse rights on the soil. The traditional order functions on the basis of personal relationships. There is little or no distinction between private and public domains.

Thus, the Law Courts and their verdict are completely alien to the tradition in which the problem of the Visvakarmas is perceived. Whatever the verdict it has only validity within the realm of the Modern State and not within the Scriptural Tradition or the Traditional Practices. (See my article, 'The Modern State, Indian Traditions and Development’ in Brouwer 1992).

As long as the Modern State and its institutions have not replaced the cognitive and empirical patterns of the other traditions, the Court rulings cannot change perceptions as in the case of the Chittoor Court case.

All traditions are always in a flux and change. We have to discover what the constants (structure) are, and what the changing elements that make up the structure are. Anthropology can be studied among all kinds of groups anywhere anytime. In my later work I have taken the knowledge I learned from the Visvakarma study to the high-tech industry and more recently to the IT sector.

Ascetics and holymen

S.S.: Jan, your effort has unearthed immense data on the Visvakarmas and innumerable folktales of the Visvakarmas of Karnataka in particular. Are there also ascetic traditions or reform or bhakti movements among the Visvakarmas similar to the Basavas in Karnatakas?

J.B.: Yes, there are similar ascetic, reform or bhakti movements among the Visvakarmas. I have seen such movements in many small towns but I must say that they were outside my focus then.

The Visvakarmas have many saints among them. Most of their stories are in my Visvakarma archive, now housed at the SRC Bangalore. Munisvara was a holyman of 16th century. The Siddappaji epic of Karnataka has both Lingayat and Visvakarma versions to it. The Munisvara shrine in Tintani in Gulbarga District is both a Visvakarma and Muslim shrine. Festivals are coordinated peacefully since centuries.

Fig. 5: Munishvara of Tintani

Contemporary context

S.S.: What are the challenges and opportunities before the Visvakarmas in the contemporary context?

J.B.: When I revisited the field in 1996 I found that all but one Coppersmith has disappeared. The only one then left was in Nagamangala (Mandya District). The range of products of Carpenters and Blacksmiths has reduced but both crafts are still needed in rural areas especially the dry regions. Otherwise carpenters in cities get orders from real estate industry and furniture showrooms. Surprisingly one Blacksmith near my house is still working as such! The best Sculptors have all survived, some of them mainly through secular work like nameplates. Goldsmiths based in small towns and villages suffer from misunderstanding of changing markets and the 14-carat rule. Urban Goldsmiths doing quite well.

My field observations ended in 1996. Since, tool issues have been taken care of by the market. Further rapid changing economy from small to large scale affects all Visvakarma craftsmen like all tiny manufacturers. Over the years many Government schemes were in place to deal with this. They met with differential response. Here is a topic for fresh research by young scholars.

S.S.: In the context of Karnataka, what are the important rituals, festivals and performing art forms specific to the Visvakarmas? Is there any ritualistic or performing art collectively performed by the Sivachar, Uttaradi, Kulachar and Matachar, as it is said to have existed in the form of Aivarkali among the Kammalar in Kerala?

J.B. :As far as I know, there is not a single festival collectively celebrated by the Visvakarmas of southern and central Karnataka, i.e. the region of the erstwhile Kingdom of Mysore. But such festival does exist in northern Karnataka at Tintani. During the days of my major fieldwork (1979 to 1984) the main difference between the northern and southern regions was one between a class orientation and a caste (jati) orientation. There could be two reasons for this. First, the Hindu reform movement led by Basavanna in the 12th century began in the northern region and later this region was under the Bombay Presidency and for a smaller part under the Nizam of Hyderabad. By contrast, the southern region was the heartland of the Maharaja of Mysore.

A question that kept me preoccupied during fieldwork is why festivals are required where you have already the narratives? The narratives can supersede local distinctions and invoke the supernatural for solutions of the stated problem. The festivals are an opportunity to give substance to the stories. The difference between the two expressions is where the inner conflict of the caste’s tradition becomes visible.

S.S.: Occasions like ayudhapuja are celebrated in most parts of India today. Visvakarma Day has been a public holiday day in Bengal, Bihar and Orissa.

J.B. Ayudhapuja is conducted by all Visvakarmas in Karnataka. The celebration of Lord Visvakarma Day on 17 September is a recent phenomenon. Interestingly it is not celebrated at their Kali temples but in a Mandir outside the localities where Visvakarmas live and work traditionally. Thus we see two things here: a change of worship from a female deity to a male deity and one from inside the locality to outside. A similar observation I made among the Devanga weavers. In their case they began to worship Hanuman in the new locality outside the old town where they worship goddess Chowdeshvari.

Fig. 6: Visvakarma Carpenters at the Wheel Lathe

S.S.: In the Visvakarma collections you handed over to IGNCA, one sees images of women Goldsmiths. To what extent Visvakarma women were involved in the work? In Kerala, one gets to see Blacksmith’s workshops being looked after by women.

Fig. 7: Visvakarma Woman Goldsmith, Chitradurga District

J.B.: In Karnataka, the woman goldsmith was only found among the Bayala Akkasaliga sub-caste of Visvakarmas in Chitradurga District as far as my information goes.

S.S.: Your books Coping with Dependence (Brouwer 1988) and Makers of the World: Caste, Craft and Mind of South Indian Artisans (Brouwer 1995) are pioneering anthropological works on the Visvakarmas in India. What are the scope and areas of further research in this field?

Fig. 8: Coping with Dependence (1988)

J.B.: The Visvakarma worldview is not only significant for the understanding of their crafts and their culture but also for the understanding of Indian culture as a whole. To gain insight into how a culture has been constituted, an examination of exceptions within that culture is called for.

This has been the starting-point for my studies on the Visvakarma caste of artisans of Karnataka. The sources used for these studies were their oral tradition—the origin myth, settlement stories, any other myth, riddles and proverbs—orally communicated; my personal participation in each of their crafts during which I even learned the secret crafts lexicon and published material.

IGNCA’s methodology is significant as it is not only multi-disciplinary but holistic. We have at our disposal major studies on the Visvakarmas of Karnataka, a huge collection of unused data collected in the same State and numerous studies by various scholars based on data in other regions. Case studies on a national scale should be envisaged. Insight into Indian heritage will be greatly enhanced when all these dispersed studies are brought together under one roof.

S.S.: What should be the focus and emphasis when one classifies the material and organizes the archive further?

J.B.: The emphasis is oral tradition and indigenous practices. The underlying assumption is that all practices are based on concepts. The concepts can be found on the cognitive level and the practices on the empirical level of everyday life. The world-view is a result of an arbitrary relationship between the two levels. The focus can be the regional variations: coastal, interior and hilly regions.

S.S.: Have you kept in touch with the community members you studied?

J.B.: A senior Indian sociologist in Bangalore advised me not to do so. But I am in touch with two members and have easy access to few others if so desired. Occasionally someone meets me in the supermarket or at signal and recalls the fieldwork days. I am touched when they remember me.

S.S.: In your work, you have used and acknowledged by name the carpenters who made drawings and also listed the names of informants and craftsmen who provided you with valuable first-hand information for your research. In my opinion, it is incredible that an ethnographer can also return to the field with her/his book and gather responses, provided one has the energy and openness left for such extended interactions.

J.B.: What satisfied me most, Sreekala, is that the Visvakarmas accepted Coping with Dependence as much as it was accepted by academics. I should also mention here the name of my classmate Dr. Joseph Platenkamp who helped me with the computer drawings. Recently he retired as Professor of Indonesian studies from the University of Muenster in Germany.

S.S.: How far your interactions with the Indian academia influenced your work?

J.B.: Besides P.K. Misra in Mysore, Prof. M.N. Srinivas in Bangalore and Prof. Veena Das encouraged me greatly to study the artisans. Prof. Misra and Prof. Srinivas urged me to collect as many empirical details as possible while Prof. Das suggested me to focus on the interface of empirical and cognitive levels.

S.S.: You said almost nothing about your stay in the North East. How was it?

J.B.: I enjoyed teaching. Students were so eager to learn. I guided one PhD student. In leisure time I worked on various papers and I was lucky to meet violinist Prashanto Dutta in Shillong and he asked me to accompany him on the piano. I was delighted and after many practice sessions we played 10 house concerts. Beside I have a number of very good friends both in and out of North East Hill University (NEHU).

Fig. 9: Jan Brouwer with his Piano at his Home in Mysuru

S.S.: During my fieldwork in Kerala in search of the performing art forms of the Visvakarmas, I was faced with a conundrum. Am I looking for art forms other than the regular vocations? In scholarly writings too, Visvakarmas are variously referred to as artisans, craftspeople and artists. Here we have a community whose traditional occupation by birth has been the art and craft of making things. Yet, the vast majority of Visvakarmas lived, far removed from the glory of the art heritage of the country—poor, alienated and often invisible.

You came from Amsterdam with a deep sense of craftsmanship and practical knowledge of carpentry, architecture and so on. You have lived here so long and had held multiple professions. How would you like to describe yourself today? Academic, musician, biker…

J.B.: Artist. An artist explores the boundaries; artist is off-roading, stretching dimensions in search of truth.

Works mentioned in the interview

Brouwer, Jan.1988. Coping with Dependence. Leiden: Druk.

———.1992. 'The modern state, Indian traditions and development' , in Development: Emerging Sociological Challenges, ed. V.N. Bhat, pp. 37–46. Shimoga: Kuvempu University.

———.1995. The Makers of the World: Caste, Craft and Mind of Artisans in South India. Delhi:Oxford University Press.

Lowe, Thelma.1989. Refractories in high-carbon iron processing: a preliminary study of the deccani wootz-making crucibles. American Ceramic Society.

Misra, P.K.1977.The Nomadic Gadulia Lohar of Eastern Rajasthan (memoir). Calcutta: Anthropological Survey of India.

Ramaswamy, Vijaya. 2004. 'Vishwakarma Craftsmen in Early Medieval Peninsular India', Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 47.4:548–82.