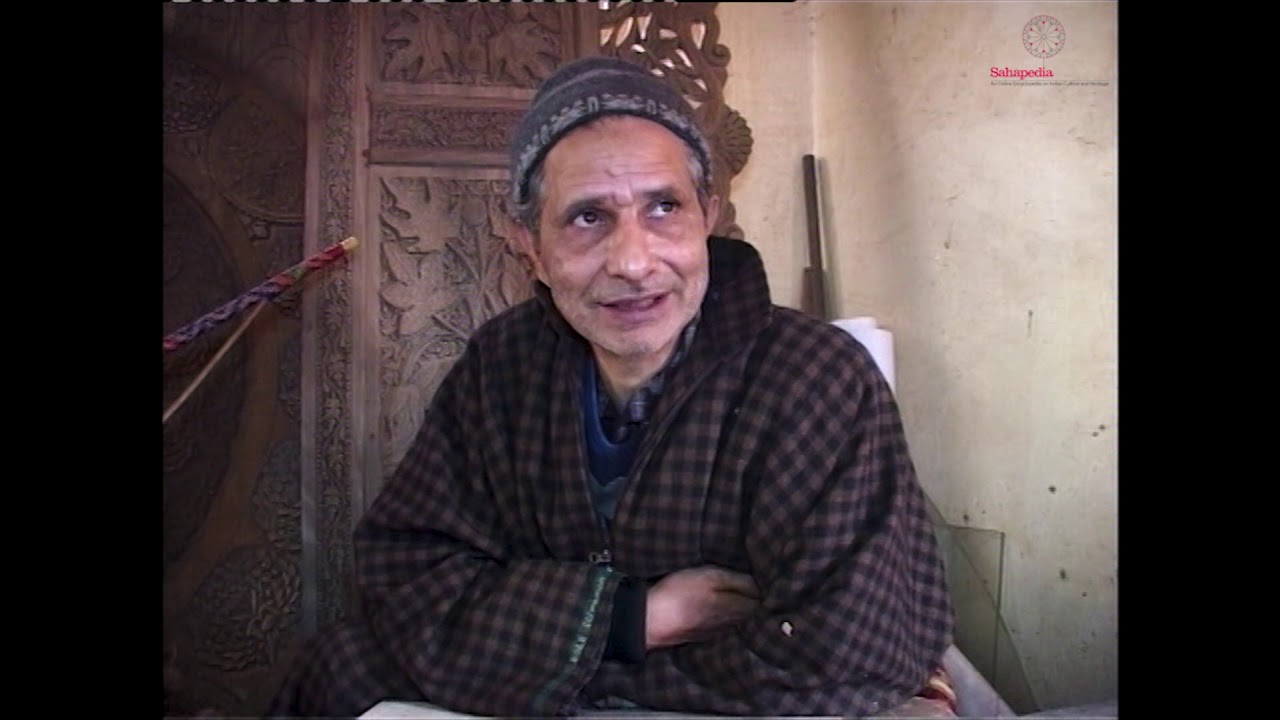

Walnut wood carving is one of the most important crafts of Kashmir. Srinagar is strewn with walnut wood carving workshops where you find craftsmen bent over the wood, chiselling and polishing. In this interview, master craftsman Ghulam Qadir Sheikh talks about life within the workshops. He talks about his initiation into wood carving and also the masters he trained under. He also gives an insight into the master-trainee relationship inside the workshops. The interview was conducted by Nikita Kaul.

Following is the translated and edited transcript of the interview.

Nikita Kaul (NK): How old were you when you started learning the craft?

Ghulam Qadir Sheikh (GQS): I was eight years old when I got initiated into this craft. At that time, my father insisted that I attend school. But I refused because everyone around me was involved in walnut wood carving and I also developed a great interest in learning this skill. I joined a karkhana (workshop) where my master told me to learn the chaar khanteh. It means a four-bordered box. We have to remove the middle portion of the box to give depth to the box. My first master was Abdul Ahad Malik. I learned the carving techniques of sumba, charkhanth and dageh in my first karkhana. I was very young then and I was very keen to learn more carving skills and so I left this karkhana and enrolled under another master. His name was Abdul Salaam Reshi. I spent three years in his karkhana and there I learnt the techniques of guzzar dunn and zameen kadunn. They were the common designs then. During my time there, I found that the brother of my then master was brilliant and more skilled. So I joined the brother’s karkhana so that I could learn various techniques and skills of this craft. Ghulam Mohammad Reshi, my third master, was a man of great creativity and imagination. In his workshop, each karigar or skilled labourer was accountable for his work but he never forced the karigars to work quickly because he did not like rough work. He never did compliment his artisans fully because, as a master, he believed that appreciation made them stop learning new things. He always would say that we have to put in great efforts to make the product more beautiful and attractive. One day he gave me a walnut wooden plank and asked me to do a guzzar process. He wanted to check how much l had learned and how well I had grasped it. I started work on it and after some time, he came by and commented that the wooden plank was really unfortunate that it came to my hands and I had destroyed it. I realised what he wanted to convey and ever since I have worked hard to do my best.

NK: Why did you frequently change your masters?

GQS: I changed my masters frequently because I was very eager to master the art of wood carving. I learned only two to three techniques at my first master’s karkhana. Then I joined another karkhana because I found that I could learn new skills there. My third master was someone who marketed his products within the country and abroad. That was why his products were so varied and creative. He had work on twenty different products going on in his workshop. So you could imagine the scope such a workshop would offer a craftsman in learning new things. He (the master) never interrupted the karigar (skilled labourer) at work because he was conscious of the quality of the final product and he also took good care of his artisans as well. He would always ask us to do our best to make the product beautiful and attractive so that the customer would get value for his money and we get appreciation and more orders. He was very insistent that the customer-craftsmen relationship should not be affected because of an inferior product. He was a great soul and he treated us like his sons. He is no more but I still love and respect him. I am very close to his family. Every person struggles in his life for some time and then he manages to overcome his circumstances and do better. Likewise, I too struggled a lot and faced many challenges when I was apprenticing. But by God’s grace, I have been able to master the skill and achieve a lot. The masters in this field have different styles of teaching. Some train you with love. Others train you harshly. My masters all had taught me the craft lovingly.

NK: What did you learn from your masters?

GQS: I learned many things from my masters. Not just the skills but also good habits and respecting the elders. Right in the beginning, I learned the process of guzzar. It means to remove unwanted material from the design so that the design will emboss. A table can have many varieties or shapes like andh-maje (oval table), khanih-maje (dining table), etc. The first table on which I did the guzzar process was 2 feet by 4 feet (2’ x 4’) long and it took four and a half months to complete it. My master said that I had done well but needed to improve my skills.

I am 53 years old and I started in this line of work since I was eight years of age. Even today I cannot say that I am a complete master of this craft as I am still learning new things every day. Knowledge of this skill is kind of an ocean which we never can really cross. I think I have managed to learn only a small part of the walnut wood carving craft. Mastery is too hard to achieve. But I have a sense of satisfaction and I am thankful to god for that. This work provides you with a livelihood. It gives you a sense of fulfillment that you have done something better in your life and not just for yourself, but also your family and community as well. I train many workers in my workshop. The customer is happy when he gets value for his money and he returns to buy again. Thus our skills and the craft are encouraged and promoted.

NK: What kind of relations did you enjoy with your masters?

GQS: I had great relations with all my masters. I left my last workshop 35 years ago but I still maintain warm relations with masters and families. A pupil who does not respect his master never really learns anything. When I started my workshop unit, my master sent me a message saying that he would always be there whenever I needed him. Afterward, he would call me sometimes for either repairing any of the tools or for some other work. And I would go and do it even it took one or two days.

NK: How many apprentices have you had so far?

GQS: At least 200 persons have come here to learn this craft. Some of them have learned well. But most of them could not learn well because they never show any enthusiasm for the learning process. It all depends on the person’s zeal, how much he learns. I learned so many techniques and processes only because I was very keen to learn and explore new things in this craft. To master any skill we have to have a great desire towards learning. You may succeed in making a good chinar motif, but with practice, you can perfect it.