Rumal is ‘an impressively designed and embroidered fabric used as a gift wrap.’[1] Chamba rumal, as Chamba kasidakari/ kadhai (embroidery) is popularly called, is a part of the larger Pahari craft tradition of Himachal Pradesh practised mostly by women since time unknown.

Chamba lies at a crossroads with several centres of art in the Western Himalayas directly connected to Basohli, Kangra and Nurpur, which interacted over time as rulers encouraged the development of Pahari arts. Pahari art and culture flourished in Chamba during the seventeenth to eighteenth centuries. The reception of Pahari paintings in Chamba rumal, which created the miniature style of embroidery beyond the pre-existing folk embroidery, especially Basohli, Chamba and Kangra kalams (schools of painting), can be traced back to constant political interactions these regions had with Chamba since the mid-seventeenth century.

Both Chamba and Kangra arts flourished under the patronage of Raja Umed Singh and Ghamand Chand, respectively, and was continued by their successors, Raja Jit Singh of Chamba and Raja Sansar Chand of Kangra. A space for free exchange of artistic ideas between Mughal court painters and local Pahari artists was created during Raja Umed Singh’s reoccupation of Rihlu and Palam from the Mughals. Under Raja Umed Singh’s expanding state of Chamba, highly skilled Mughal painters along with Pahari painters together formed the various Pahari kalams of painting that we know today. The Pahari arts, as well as the Chamba rumal, thus developed through an interaction and exchange of ideas and techniques. For example, the Lakshmi-Narayana temple inscription of King Sri Simha of Chamba (1858–1860 CE) mentions an artist scribe, Upadhyaya Mirachu, settled there from Basohli; further, the annexation of Rihlu by Maharaja Ranjit Singh, 1821 CE, opened up the possibility of the reception of colourful Punjabi style of painting with the predominance of yellow, among other colours, on the art of Chamba. Miniatures and embroideries were offered as gifts to maintain political alliances, and artists were sent to other regions so that the arts could mutually develop their skills.

Because of its name, Chamba rumal is often confused for a literal handkerchief, but it refers to the art form of Chamba embroidery, which involves various stitching styles, techniques, images and most importantly, stories. Chamba rumal extends across various artworks like double-sided frames, handkerchiefs, covers, belts, sheets, shawls, dupattas, fans, and more. The embroidery is intertextual as literature and paintings are reinterpreted and one cannot distinguish paintings, stories and embroidery from one other when woven as one in the final creation.

Chamba rumal can be categorised as a folk style of embroidery which has been prevalent in Chamba in various forms like coverings, patwars (belts), cholis (blouses), caps (Fig.1), scarves, pillow cover, household accessories, chaupar (dice game) cloth, bedstead, wall hangings, chandwas (ceiling covers), and pankhas (fans). It was mainly used as decorative covers on offerings made to deities or a coverlet of gifts from the bride to the groom’s family to exhibit the embroidery skills of the bride, and was also widely used as dhaknu (square cover) and chhabu (circular cover). An instance of it used as a cover can be seen in a Kangra painting depicting Brahmin wives carrying offerings to Krishna in a casket covered with an embroidered rumal.[2]

In addition to the folk style, the miniature-based form of Chamba rumal based on Pahari paintings and Rang Mahal wall paintings (Fig.2) came up in the eighteenth century when the royal women took an interest in the art. Painters at their courts drew the outlines on fabric and then they were embroidered upon using pat (naturally dyed untwisted pure silk floss) or badla (silver gilt) on unbleached muslin. The miniature-style rumals also saw changes in the colour palette as instructed by the painters in most cases. Unlike bright shades used in the folk style Chamba rumals, miniature-style Chamba rumals used softer and muted shades.

Chamba rumal is made by using the do rukha tanka technique which has remained consistent over time. In this technique, a double satin stitch is done simultaneously on the back and front so that there is no wrong side. It starts from one end, after the outlines are filled using long and short satin stitches in various directions to produce the desired effect. The double satin stitch also brings out the sheen of the embroidery. Bandi tanka (stem stitch) is used to outline figures and floral borders.[6]

The threads manufactured now are different from those in the past when threads were dyed with majith (madder) for red colour, indigo for blue, molasses for brown, naspal (bark of the tree) for light brown, kusumba for orange, kesoophool for yellow, kai (moss) for green and iron scrap for black colour; alum was used on them as mordant to make the colours permanent. Today, embroiderers often use untwisted silk and synthetic silk threads, apart from newer natural processes taught at training centres in Chamba. As the right kinds of thread for the delicate art of Chamba rumal making is scarce these days, artists stock them up from places such as Delhi and Chamba whenever they chance upon threads of their preference.

Themes and Motifs

Ram te Lachhman chopar khel de, Siyarani kadh di kasida ho’

(Rama and Lakshmana play chaupar while Sita is engaged in embroidery)[3]

[from a Chamba folk song]

Before the advent of miniature style kasidakari, the Chamba rumal woven by women of the hills had themes from the daily life of Chamba, its landscapes and themes related to its faith, which included drawings of Shiva, Krishna and Rama. Their embroidery was distinct in the manner in which the motifs were drawn. Since these embroiderers were not miniature artists, their drawing technique was without the distinctive details that typify the works of the miniaturists; for example, there are Chamba rumals with parrot beak-like shapes for a human mouth and small round faces without prominent features. The colour palette of the hill women was vibrant and bold. The miniature style brought a naturalistic technique with precise outlining using the square-layer brush, and the colour palette was softened using muted shades of the bright colours.

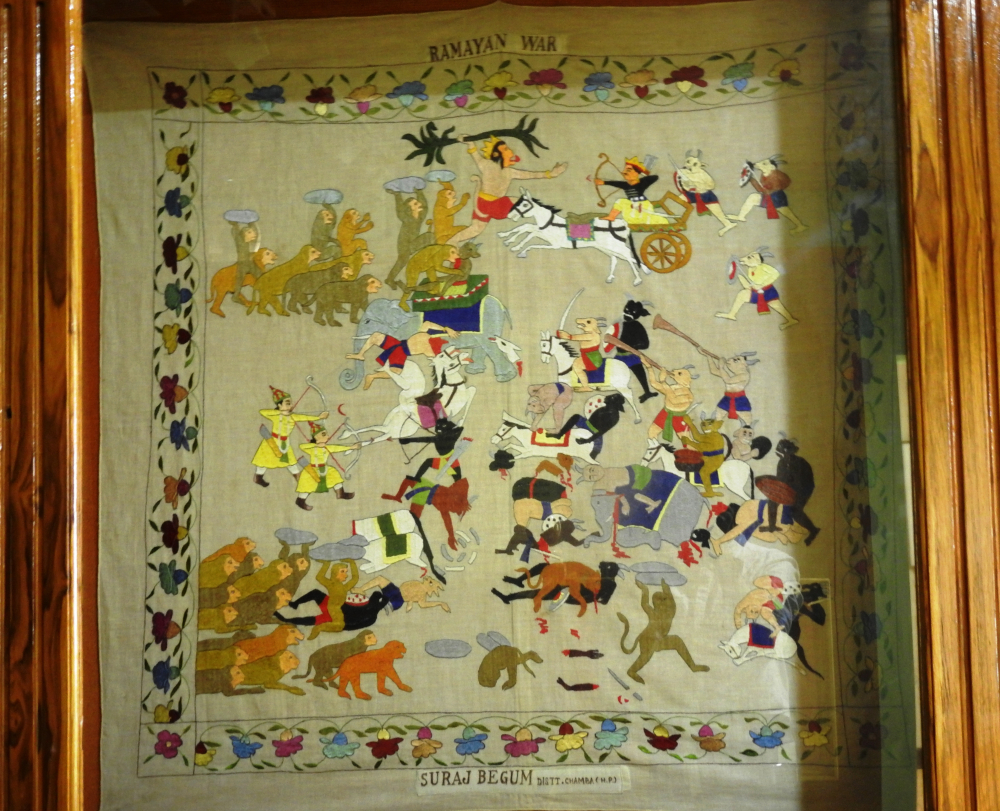

As Chamba rumal also borrowed from the Kangra, Guler and Basohli schools of painting, the rumals carry themes encompassing stories like Gitagovindam (a twelfth-century text on Krishna by the poet Jayadeva), Ramayana (Fig. 3), Mahabharata, Bhagavad Purana, Raasmandala (an episode of the dance of Krishna), Parijata Haran (episode of Krishna uprooting the parijata tree for his wife), Kurukshetra Yuddh (the epic war from Mahabharata), Rukmini Haran (Fig. 4, the episode of Krishna and Rukmini’s wedding in Mahabharata), Kaliya Daman (an episode from the life of Krishna where he defeats the serpent Kaliya), and Baramasa (a folk song of the region). Rumals embroidered with scenes from Rukmini Haran were used as sacred hangings in mandapams (wedding venues).[4]

There are various Chamba rumals that retell stories revolving around the legends of Krishna. Raasmandala (Fig. 5) is also a commonly embroidered story in Chamba rumals. It shows Krishna sitting in the middle on the motif of a padma (lotus), stretching out his four arms holding a padma, gada (weapon), shankha (conch), and sudarshana chakra (Vishnu’s spinning disk-like weapon) and is surrounded by dancing gopinis (cowherd girls). The guldastas (bouquets) and gopinis playing dholaks are embroidered on the four corners of the rumal and it is finished off with a floral border inspired by hashiyas (margins) of the Guler-Kangra paintings. Krishna’s attire, especially the conical headgear, is drawn from the Chamba kalam and is common in both the folk and miniature style embroideries.

The Raagmala theme, based on Hindustani classical music, has been a widely used in Pahari paintings; in it we find a melange of poetry, music and painting creating new intertextual dimensions where poets composed verses for artists. An illustration of Chamba rumal based on the ragas can be found in the Bharat Kala Bhavan, Banaras Hindu University, where a preserved rumal shows Todi, Gauri, Madhumadhavi, Gaur Malhar, Patmanjari, Malkauns and various other ragas through various scenes and tales involving deities, nayak-nayika (hero-heroine) set against different seasons, places and times to bring out the rasa (essence) unique to each raga.

Seventeenth century onwards, Keshav Das’s text Rasikapriya became popular among Pahari painters, which later came to be extensively received in Chamba rumals capturing the layered moods of courtship through the depiction of the ashtanayika (eight types of heroines defined in Bharata’s Natyashastra, seminal performance arts text of the Indian subcontinent).

The rumals also carry themes from local stories and customs like the Minjar Mela Jalus (monsoon festival of Chamba where people throw minjar [tassels] in river Ravi to ward off the evil and pray for prosperity), Gaddi Gaddan (Fig. 6; man and woman of a shepherding tribe that resides in the hills of Himachal Pradesh), Manimahesh Yatra (an annual pilgrimage undertaken by worshippers of Lord Shiva in Chamba), Ved Vedi (wedding pavillion/mandap), Til Chauli (a traditional ceremony at Chamba weddings where women dance and sing; black sesame seeds [til] and rice [chaul] form an integral part of it), folk tales like love story of Sassi Punnu, and so on. Dynamic scenes from the court and daily lives of the people are also embroidered, like the themes of shikargah (hunting), godhuli (sunset) (Fig. 7), and chaupar (Fig. 8).

Local flora and fauna are recurring motifs in Chamba rumal. There are different kinds of floral patterns where one sees dense or barren trees with various styles of flowers and leaves. The drooping cypress trees are inspired by the Pahari-Mughal art banana trees;[5] the barrenness and blossoming of trees reflect the moods and emotions of characters, especially when a rumal illustrates a story. Various birds and animal motifs are made to depict moods while weaving the tales of Radha-Krishna, Rama-Sita, Raagmala or ashtanayika. Elements like peacock, chakor, duck, parrot and swan help bring out various moods of the lover, and elephants and horses mean courtly grandiose; motifs can also be symbolic such as in the ashtanayika series (Fig. 9) where the snake at the nayika’s feet symbolises danger, wilting flowers show her viraha (sorrow) and the blooming flora interacts with the hope of union she feels.

Motifs of musical instruments form important symbols in the depiction of Raagmala, Raasmandala, Rukmini Haran, and festivals like the Minjar Mela Jalus. Be it a rumal set in a story from the court or a local story based on the life of the common people, we see an abundance of dholak, dholakia (dholak player), tanpura, veena, khartala (percussion instrument), sitar, and more such musical instruments in embroidery.

Crises and Revival

After Independence when the princely states were integrated with the state of India, the Chamba rumal craft tradition went through a major crisis due to loss of patronage. The art faced a decline in the last century and the rumals became inferior in design and artistic skill; many practitioners also started finding it difficult to continue as rumal makers.

The efforts of Kamala Devi Chattopadhyay, the driving force behind the revival of Indian handicrafts and theatre post-Independence, facilitated the revival of the Chamba rumal, and the first centre dedicated to Chamba rumal making was set up in Chamba, with Maheshi Devi as its head. The centre trained women and even provided them with a stipend; famous Chamba rumal artists like Rajinder Nayyar, Lalita Vakil, Suraj Begum were all associated with it.[7]

However, in the 1980s–90s, the art of rumal making in Chamba faced another stumbling block as Chattopadhyay’s government-run centre closed. There were next to no similar avenues, and with the last of them a centre set up by artist Kamala Nayyar, which lasted just a year.[8] This time, the revival was ushered in by Delhi Crafts Council in 1996 through initiatives for conservation of Chamba rumals, and studies on the art form from available artefacts at museums and private collections. With the help of the surviving artists from Chamba, the initiative brought a new generation of artists together. A training centre, CHARU (abbreviation of Chamba rumal) was opened on April 3, 2002, at Chamba, coinciding with Kamaladeviji’s birthday. The centre also carried out new experiments with regard to fabrics and new ways to naturally dye threads. Award-winning senior artists like Masto Devi train students today at the CHARU centre. This initiative encouraged the art further and, today, several young artists in Chamba are starting to pursue Chamba embroidery professionally.

Chamba embroidery paints life through the needle which is why young artists today come up with new stories, ideas and motifs. Heena, a Chamba rumal artist, strongly advocates the importance of being able to think independently so that newer stories can be incorporated through which artists can voice themselves beyond the previously carried out copy-work of the old rumals.

The changing consumer dynamics bringing middlemen into the scene often leads to artists being underpaid for their works whereby they’re sold at exorbitant prices by designers and organisations that source them from artists. Therefore, many rumal artists today, such as Indu Sharma and Heena, have started using social media to establish direct contact with their customers. They also explore and experiment with not just themes but newer products like bookmarks, jewellery, and more, thus expanding the scope of Chamba embroidery. They work on customised orders, commissioned art as well as their independent projects.

Notes

[1] Subhashini, Folk Embroidery of Western Himalaya.

[2]Bhattacharya, A Pictorial Handicraft of Himachal Pradesh, Indian Museum.

[3]Sharma, Documentation of Decorative Motifs and Design in Hill Embroidery.

[4]Kaur, ‘Chamba Rumal.’

[5]Sharma, Documentation of Decorative Motifs and Design in Hill Embroidery.

[6]Grewal and Grewal, The Needle Lore.

[7] Rajinder Nayyar, in conversation with the author.

[8] Indu Sharma, in conversation with the author.

Bibliography

Bhattacharya, A. A Pictorial Handicraft of Himachal Pradesh. Calcutta: Indian Museum, 1968.

Grewal, Amarjit, and Neelam Grewal. The Needle Lore: Traditional Embroideries of Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan. Delhi: Ajanta Publications, 1988.

Jasminder, Kaur. ‘Chamba Rumal: The Painting by the Needle.’ International Journal of Research-Granthaalayah 5, no. 6 (June 2017): 18–32. Accessed August 21, 2020. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318360655_CHAMBA_RUMAL_THE_PAINTING_BY_NEEDLE

Goswamy, B.N. Pahari Paintings of the Nala-Damayanti Theme in the Collection of Dr Karan Singh. New Delhi: National Museum, 2006

Subhashini, Aryan. Folk Embroidery of Western Himalaya. Delhi: Rekha Prakashan, 1992.

Sharma, Vijay. Documentation of Decorative Motifs and Design in Hill Embroidery: Especially in Context of Chamba Rumal and Backless Cholis. Chamba: 2005.