Encountering an ‘alien’ or unfamiliar object in some little-known Indian collection, or an Indian inscription in the unlikeliest of artwork speaks volumes about how objects of art travel across the world. Prof. B.N. Goswamy attempts to uncover the mystery of Devanagari engravings on French paintings and French engravings in Rajasthan. (Photo courtesy: The Tribune)

This article appeared originally in The Tribune, Chandigarh and is reproduced here with permission.

The manner in which objects of art, and along with them influences, travel at times is something that continues to fascinate me. The ancient times—when unheralded caravans, laden with goods, used to arrive from unknown territories and pilgrims or seekers from other lands made their way to ours—were somewhat different, for precise documentation does not belong to them, but one knows of so many movements that have been exactly recorded. To take random examples: Jesuit fathers would bring sacred paintings and printed images to the court of the great Akbar and would be received with great courtesy; an 18th century shipwreck by the name of Ram Singh Malam would return to his native Gujarat after a stay of nearly 11 years in Europe, and have in his baggage a sheaf-full of views of European cities; Japanese artists would arrive at Shantiniketan, make it their home, and share with the likes of Abanindranath Tagore their vision and their skills. The theme can be spoken of, or written about, endlessly. But, to be candid, even now when one comes upon, unexpectedly, an ‘alien’ or unfamiliar object that had made its way to some little-known Indian collection, the sense of surprise does not leave one. Like it did not when, recently, going almost casually through a small private collection in California, I chanced upon two 18th century French engravings that must have come to India some 200 or more years ago.

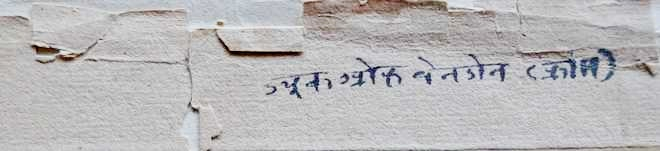

One of them featured an elegantly attired French general, Louis Joseph (1654–1712), with his handsome figure dominating over the scene of a fortified town under siege. One sees the man, celebrated to this day as “one of the most remarkable soldiers in the history of the French army”, who had, “besides the skill and the fertile imagination of the true army leader, the brilliant courage of a soldier”, standing, casting a long shadow, while in the background, finely drawn, men are carrying wounded soldiers, grenadiers bustle around large cannons, and billows of smoke rise from explosions that have breached the walls. The general, identified in the caption of the engraving below as “Duc de Vendome”, cuts a superb figure: dressed in the height of fashion—bicorne hat worn sideways, ringlets of a wig cascading down the shoulders, brilliantly coloured scarlet coat with the ample cuffs of its sleeves folded back, tight-fitting breeches—he is seen looking not at the action behind him but away so as to show us the noble cut of his youthful face. Or is it that he is about to shout instructions to some subordinate, having espied something through a telescope that he holds prominently in one hand? Whatever the case, of obvious interest in the context of this piece, is the fact that this fine early 18th century engraving carries another caption or label above the top margin, written at an angle in old Devanagari characters, which reads: “duke oaf vendon (phrance)”. The inscription is not in the hand of a recent dealer through whom the engraving might have been acquired, but is almost certainly placed there by a librarian or keeper intent upon identifying the subject of the work before entering it into records. How, or why, this French work made its way here—to Rajasthan, in all likelihood—remains as unknown as the person who might have been interested in acquiring it.

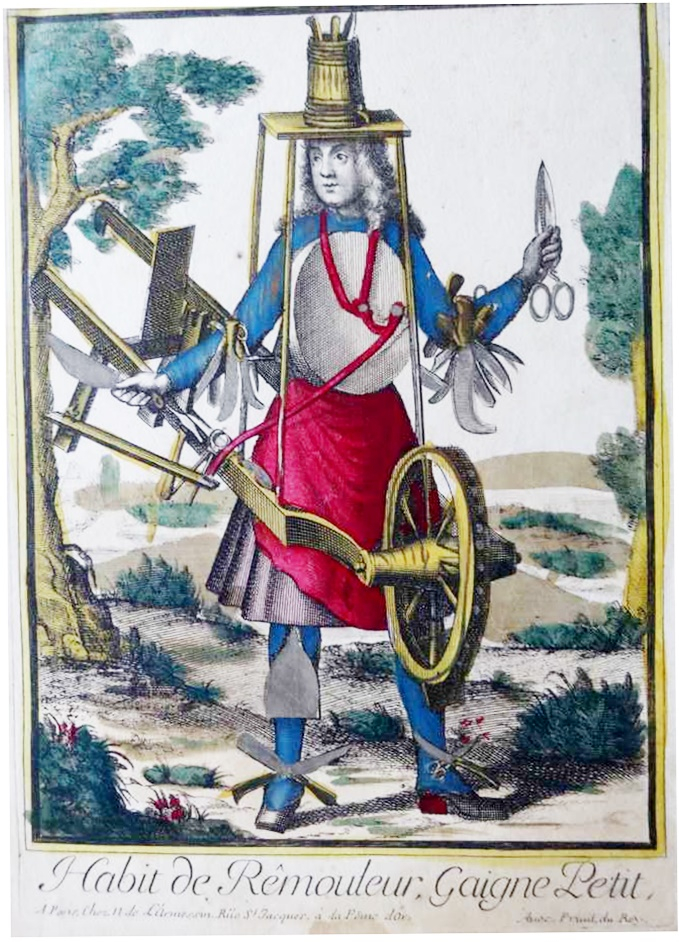

In the same lot, and certainly acquired at the very same time, is another engraving—also clearly French as can be ascertained from the caption below—featuring a man virtually armed to the teeth, not because he is a soldier, but because he plies a trade which he advertises through what he wears and what he carries: an extraordinary range of objects, including knives of all shapes and sizes and scissors of different kinds which he has tied to all parts of his body, from hands to elbows and from knees to ankles. He is, as the French caption explains, a ‘remouleur’, ‘grinder’ in other words, who moves from village to village, even from house to house perhaps, offering to sharpen, and grind into shape, old but blunted knives and scissors. One recognises the trade, for itinerant grinders used, at least once, to be a common sight in our land too, but the manner in which the man is accoutered, and the apparatus with a wheel, with a part of which he covers his head like a helmet, must have presented an astonishing sight to the Indian collector who acquired it. One might have been tempted to regard this as an arresting French engraving with no connection to India, but, once again, as in the case of the image of the Duc de Vendome, on the top margin of the engraving is a caption, in Devanagari script. The one word inscription simply reads, ‘sikligar’, the word used to identify in our land, especially in Rajasthan, persons who worked with metals, particularly those fashioning vessels and weapons like swords and daggers. A chord must have been struck.

Also read | Art N Soul: The ‘Timeless’ Indian Shawl

Also read | Art N Soul: What Happens in the Margins

To find English engravings in Indian collections leads, generally, to no surprise, but French engravings in Rajasthan? One begins to wonder. Adding to these thoughts I saw, in the same Californian collection, an intriguing but superbly drawn Indian painted sketch, just possibly triggered by the engraving of the intriguing looking ‘grinder’. It featured an oddly dressed man—furry hat with a flamboyant ‘aigrette’ sticking out, heavy short-sleeved jacket flaring at the knee level, brass belts and tassels around the waist and knee and ankles—moving with a dancing step while holding in both his hands pairs of khartals, those narrow and long castanet-like wooden strips that worshippers strike while singing devotional songs. Who is he, this strange-looking, free spirited man? And what is that curved calabash-like object, which reminds one of a powder-horn, hanging from his belt?

This article has been republished as part of an ongoing series Art N Soul from The Tribune.