Story of a 16th-century Asian ivory casket that was carved in Sri Lanka has a fascinating history of colonial and evangelising power. Now exhibited in London, Prof. B.N. Goswamy revisits the connection between this art piece and an engraving by the great German artist Albrecht Durer. (Photo courtesy: The Tribune)

This article appeared originally in The Tribune, Chandigarh and is reproduced here with permission.

Art, from the Medieval point of view, was a kind of knowledge in accordance with which the artist imagined the form or design of the work to be done, and by which he reproduced this form in the required or available material. The product was not called “art,” but an “artifact,” a thing “made by art”; the art remains in the artist. Nor was there any distinction of “fine” from “applied” or “pure” from “decorative” art. All art was for “good use” and “adapted to condition.” Art could be applied either to noble or to common uses, but was no more or less art in the one case than in the other.

— Ananda Coomaraswamy

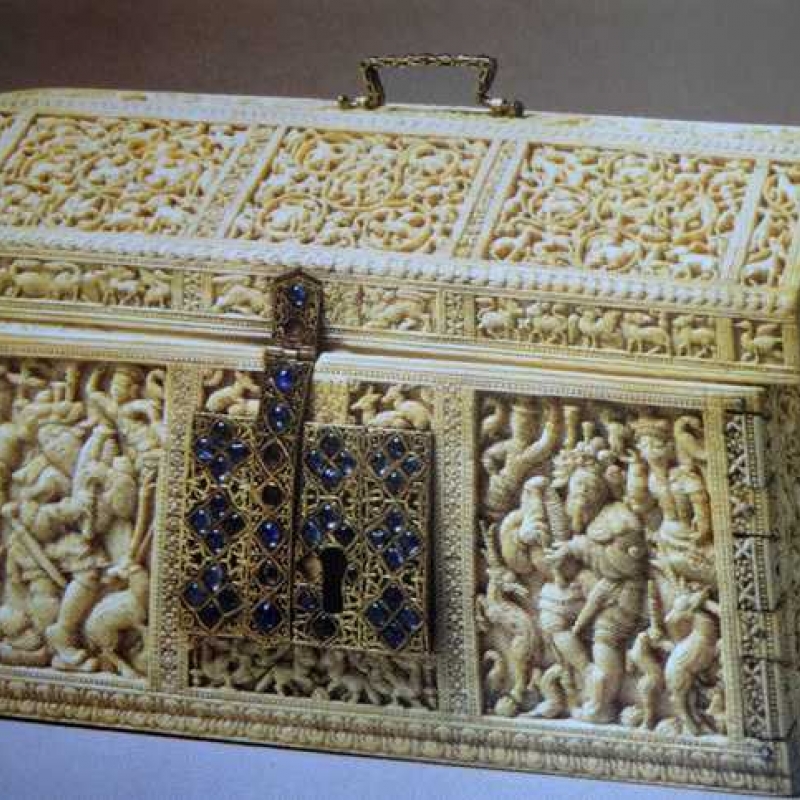

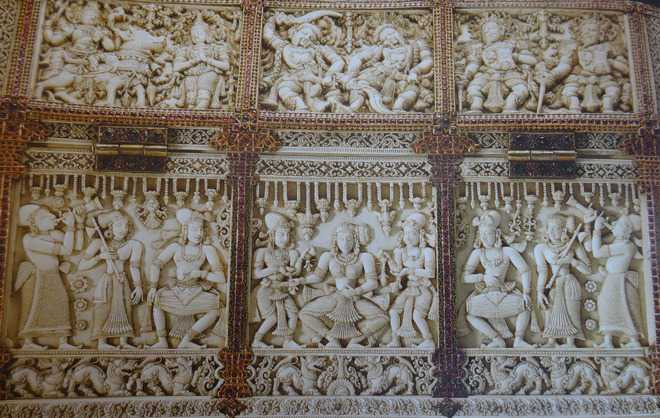

There is, in the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, an ivory casket, one of a group of nine, which is generally referred to as the ‘Robinson Casket’, named as it is after the Superintendent of Art Collections who, having bought it in Lisbon late in the 19th century, gifted it to the Museum. The casket has a most fascinating history, for it was neither Portuguese in origin, nor was it produced in the 19th century. It was made in Sri Lanka in the middle of the 16th century—much the Medieval period to which the great savant, Coomaraswamy, refers in the excerpt above taken from one of his countless writings—for the prince of Kotte in that island kingdom. This is how this brilliantly carved casket is described in the records of the Museum: “Ivory casket, ‘Robinson Casket’, carved with Biblical scenes, with silver hinges, gold filigree and sapphire ornamentation, Kotte, Sri Lanka, ca. 1557.”

My attention went to the casket not because I had seen it recently but because of an article by Sujatha Arundhati Meegama, writing on the ‘Connected Art Histories of Sri Lanka’ in the Marg magazine, in which she discussed it, focussing specially on the presence of a carved figure in one of its panels which was based on a 1514 engraving by Albrecht Durer, the great German artist of the Northern Renaissance in Europe. The superbly drawn figure in that engraving is that of a coarsely dressed bagpiper, a shepherd perhaps, leaning against a tree, playing on his instrument, and looking to his left, eyes alight with merriment. How that bagpiper found his place in the work of a gifted but evidently traditional ivory carver in Sri Lanka can only be understood in the context of what was happening in the mid-16th century in Sri Lanka.

As a colonial and evangelising power, the Portuguese had entered the waters around Sri Lanka at this time, and had clearly become a force to reckon with. The then King of Kotte, who had many rivals, wanted to ensure that after him his grandson, Dharmapala, succeeds him, and approached the Portuguese for support. That support was given: an embassy was sent in 1542–43 from Kotte to Lisbon, and there the young Dharmapala was symbolically—through an effigy—but formally, recognised by the Portuguese ruler to be the successor-designate to the throne of Kotte. There was, in the background of all this, the hope on the part of the Portuguese that the Kotte king would, in return for this support, convert to Christianity and, with that, will the whole kingdom. This, which would have been seen as a missionary triumph, did not happen immediately, but when, in 1551, Dharmapala actually succeeded his grandfather, the conversion did actually take place. The initial hesitations, based on the fear of opposition from his Buddhist subjects, were thrown aside and, in 1557, Dharmapala formally embraced Christianity. A letter was written to the king of Portugal announcing this and it was carried home, joyously, by Franciscan missionaries active in Sri Lanka. There is no clear mention of the gifts sent by Dharmapala to Portugal on this occasion, but it is fair to speculate that among the gifts was this ivory casket, made especially for this occasion. Christianity, and Christian belief, is writ all over the casket, panel after delicate panel featuring it.

Also read | Art N Soul: How the Louisa Parlby Album Depicts 18th Century India

The great ivory carvers of Sri Lanka, sensitive to changing times on their own, and also possibly urged through a royal decree, must have set about their task of turning out this remarkable casket, joining Sinhalese skills with Christian themes. Depicted on it, one sees the Betrothal of the Virgin, the Flight into Egypt, the Tree of Jesse—all established Christian subjects—mingling with local, Kandyan apsaras and musicians and dancers. Clearly, printed European religious images must have been everywhere, having arrived in the baggage of the missionaries, and the carvers must have seen them. The Bagpiper of Durer, and the two village dancers also by him, were made by them to mingle with local crowds and semi-divine figures celebrating events with gay abandon on exquisitely carved ivory panels.

“All the days of my life, I have seen nothing that rejoiced my heart so much as these things,” Durer wrote once on seeing some gifts sent by an Aztec ruler to the king of Spain, “for I saw amongst them wonderful works of art, and I marvelled at the subtle ingenia of people in foreign lands. Indeed I cannot express all that I thought there.” The great artist would certainly have been excited by seeing his work integrated with the intricate carvings on the ivory casket that we have been talking about. But he was no longer alive in 1557, having died 30 years before.

This article has been republished as part of an ongoing series Art N Soul from The Tribune.