Controversies and all, historians of Indian art tend to take another view of the 18th century Chief Justice Sir Elijah Impey. For he was a man who, despite all the prejudices he must have brought with him, became keen on Indian art. Prof. B.N. Goswamy talks about how some of the finest work turned out at the end of the eighteenth century in India was done for Impey. (In pic: left, A representational picture of a ragamala painting depicting Todi Ragini, and a portrait of Sir Elijah Impey; Photo courtesy: Wikimedia Commons)

This article appeared originally in The Tribune, Chandigarh under the title ‘A Chief Justice’s Collection’ and is reproduced here with permission.

Not many people are likely to be aware of it at this stage, but a major exhibition, celebrating 50-years of the Supreme Court of India, is currently under preparation. It will go up at the National Museum in Delhi in less than a month’s time from now, and should—considering the feverish activity in evidence at the museum now—be an absorbing event, something to look forward to and learn from. Few know what exactly would go into the show, although it is a fair guess that the distant past will not be left out of it. And the past brings back, as always, memories.

The eighteenth century is a long way off, but I am certainly reminded of the remarkably active interest that the very first Chief Justice of a court in British India, Sir Elijah Impey, took in the art of this land. Many will know the name well, for history tells us much about this man who, in Macaulay’s unjust but ringing phrase, was “rick, quiet and infamous”. Impey was in India for just a little over eight years but, in this short span of time, he, together with his distinguished school-mate and the first Governor General of India, Warren Hastings, stirred up enough controversies to become the subject of a debate which still finds partisans among historians.

Also read | Art N Soul: The Silk Route to Burma via India

In these crowded years the unsavoury drama of the Nandkumar case, which shook British India and in which Impey had a cardinal role, played itself out. Allegations that he was Warren Hastings’ “convenient tool” rang in the air, not only here but also in England. And Impey’s recall, in 1782, was followed a few years later by his impeachment, together with that of Hastings—proceedings which gave rise to some of the most brilliant flights of oratory in the history of Parliament—on this and many other counts. The barbs in the polemics were singularly bitter although Impey managed eventually to hold his own. He survived the impeachment attempt by a quarter of a century; slander, however, continued to dog him, and Macaulay kept insisting that no other judge “had dishonoured (more) the English ermine since Jeffries drank himself to death in the Tower”.

Controversies and all, historians of Indian art tend to take another view of Sir Elijah Impey. For he was a man who, despite all the prejudices he must have brought with him, became keen on Indian art. Together with his wife, Lady Mary Impey, there seem to have been many projects that he got involved in, many Indian artists who, in those languishing years, he employed. In fact, some of the finest work turned out at the end of the eighteenth century in India was done for the Impeys, and Zain-al Din, Ramdas and Bhawani—three of the artists working for them—were in part responsible for those large and sumptuous studies of birds, plants and animals that one so celebrates today.

There is much keenness of observation in these studies and while the work may not be able to compete with that of the great Mughal master, a certain crispness of execution in them leaves one affected. The work must have gone on for years, and one can almost visualise the artists bringing their work periodically to these new patrons of theirs and having them carefully examined and commented upon, much in the manner in which this was done for Indian patrons in the past.

Also see | Revealing the Faces Behind Assam’s Mask-Making Culture

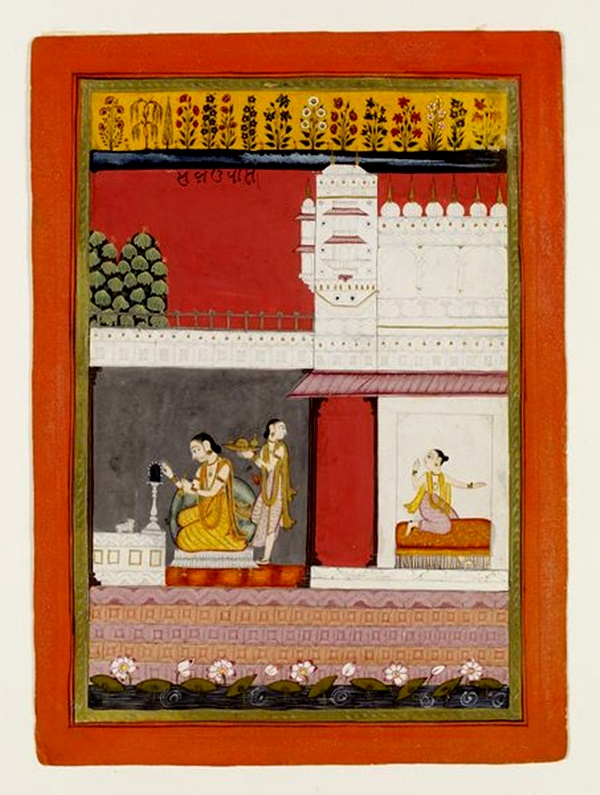

There is then that series of pictures which we today know as the ‘Impey Ramayana’, each folio of it bearing the seal of the Chief Justice, with its legend in Persian, at the back. Among the most fascinating of the works linked to the Chief Justice, however, is a group of paintings of the Ragamala theme that, years ago, I chanced upon, together with a colleague of mine, in the collection of a foundation at Heidelberg in Germany, the von Portheim Stiftung. Fascinating, because there is evidence in the painted leaves themselves of the degree to which Sir Elijah Impey involved himself in the work that he commissioned or acquired here.

The Ragamala—personifications in visual form of modes of Indian music, all those ragas and raginis that we know well-could not possibly have been a theme that Impey was familiar with. For him to be drawn to them is a fact interesting in itself, therefore. But even more interesting is the fact that the protective fly-covers attached to the paintings are filled with long notes in Hindustani, written in the Latin script, apparently in Sir Elijah Impey’s own hand. These notes are renderings—in broken English-Style Hindustani prose—of the Hindi verses inscribed on the paintings themselves, and their point seems to be to try and understand what the Hindi texts say.

To take an example. In the panel above the painting of the Kamodini ragini, showing her seated praying at a shrine, the verse begins: “Kamodini ati biraha satai/hath jori kari seva lai”. In the Sahib’s Hindustani—something that some engaged pandit must have helped him with—it turns into: “Kaummoad raugnee. Is ka dil ma bahut iskud hy ore oos ko kauvind is ka pas nahinhy”. Meaning, in plain but literal English, of course, that “in her heart there is much love, and her husband is not near her”. So on it goes, text after factured text, leaf upon leaf. But, awkwardness and all, what shines through in all this is a certain seriousness of purpose, a dedication to the task in hand. Even an attempt perhaps—considering the choice of complex theme in these paintings—at understanding what trulyu moved the Indian mind.

More Hindustani, English style

In one of the paintings in the Impey Ragamala series, there is a scene of worship, and the word Salagrama occurs in the text. understanding the nature and the meaning of this ammonite stone, so sacred to Vaishnavas, could not have been easy for the Chief Justice. Recording, therefore, what the pandit must have started explaining to him, he notes: “Jabtuck zammeen par Brumhaa, Bishnoo,” Roodr Voghyra devtau, audmee ka soorat ma rata tha, is vaski jo audmee to oos audmee ka ukkal ore sub cheese jo hy sub droost tha...” Apparently, it was not easy going for the Chief Justice; as indeed his words are not for us.

This article has been republished as part of an ongoing series Art N Soul from The Tribune.