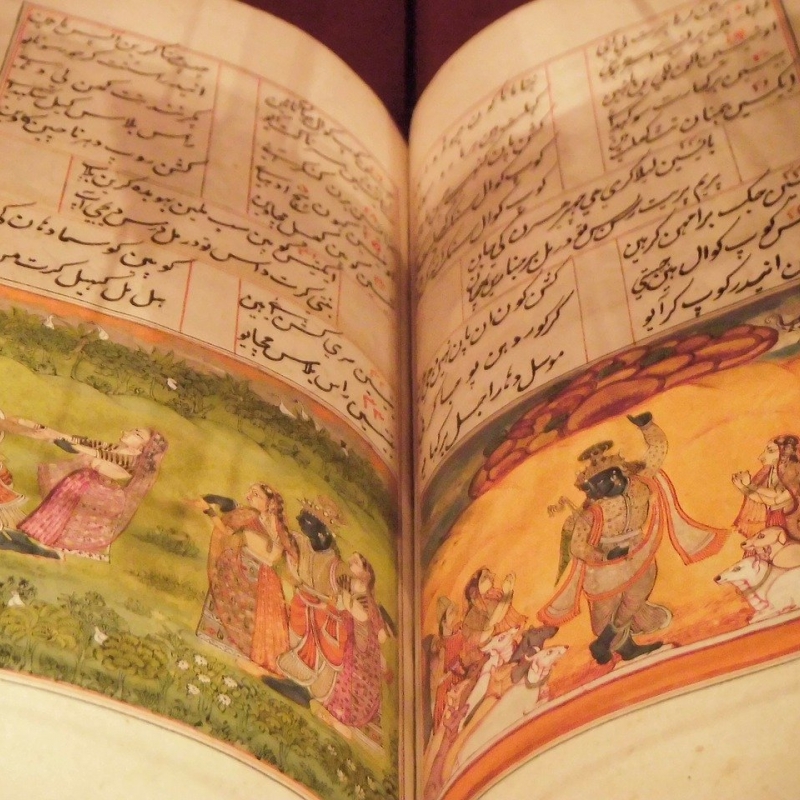

The Bhagavad-Gita, one knows, is not an easy text to ‘illustrate’, for it is essentially philosophical in nature, filled with complex and abstruse thoughts. However, in the volume, ‘La Bhagavadgita illustree par la Peinture Indienne’, the editor and publisher draw upon a host of images that lead one into the visual context of each ‘teaching’, opines Prof. B.N. Goswamy. (In pic: An ancient Bhagvad Gita manuscript from the John Rylands Library, Manchester; Photo courtesy: Pixabay)

This article appeared originally in The Tribune, Chandigarh and is reproduced here with permission.

“In the morning I bathe my intellect in the stupendous and cosmogonal philosophy of the Bhagvatgeeta, since whose composition years of the gods have elapsed, and in comparison with which our modern world and its literature seem puny and trivial; and I doubt if that philosophy is not to be referred to a previous state of existence, so remote is its sublimity from our conceptions. ….” — Henry DavidThoreau in Walden (1845-1847)

“I owed — my friend (Thoreau) and I owed — a magnificent day to the BhagavatGeeta. It was the first of books; it was as if an empire spoke to us, nothing small or unworthy, but large, serene, consistent, the voice of an old intelligence which in another age and climate had pondered and thus disposed of the same questions which exercise us.” — Ralph Waldo Emerson (in 1845)

The great American naturalist and author who wrote the words contained in the first passage cited above had withdrawn from his world to live near Walden pond, away from his fellow-men who, to use his phrase, led “lives of quiet desperation”. There, the poet-philosopher Emerson had joined him, and the two would, day upon day, share their thoughts and their questions in that quiet corner of Massachusetts. The one ancient text that moved them—‘shook them’ might express their states better—was the Bhagavad-Gita—and in their writings they kept going back to the great work for, through it, they got the sensation of the ‘pure water’ of their Walden pond ‘mingling with the sacred water of the Ganges’.

Also see | The Many Mahabharatas of Rajasthan

But what, one might ask, is the occasion for me to turn to the Bhagavad-Gita at this moment? It is not that this great text—that has steadied minds over centuries, offered solace, raised visions, charted courses of life—has ever been far from one’s thoughts; it is the publication of a fine version of it in French that has just appeared and that I find compelled to draw attention to. ‘La Bhagavadgita illustree par la Peinture Indienne’ is the title that the book brought out by the famed French house of Diane de Selliers bears. One knows that publishing house, at least in India, for its magnificent publication some years ago of the Ramayana in seven volumes, filled with the riches of Indian paintings that bring the great epic, visually, within our reach. And now, close on its heels, comes from the same house this sumptuous publication, rich not only in its text and other essays, but also in the images which it brings together.

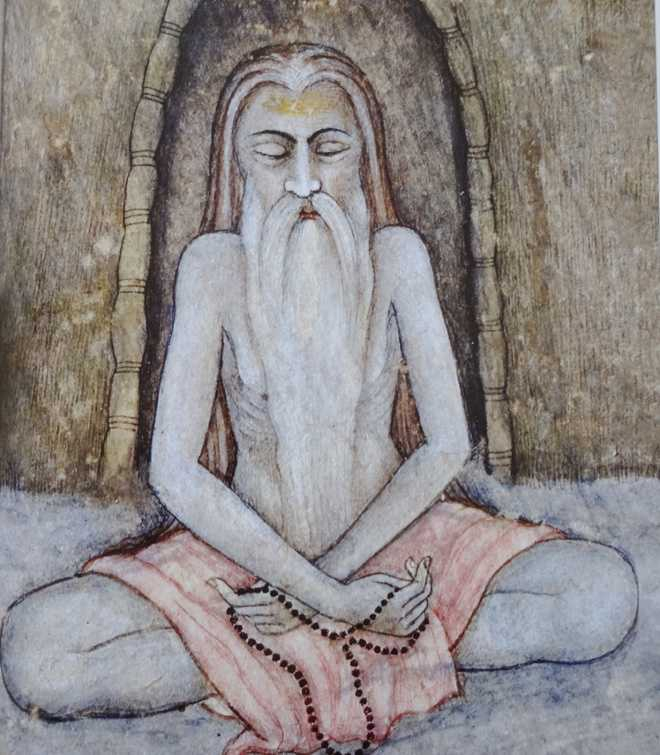

The Bhagavad-Gita, one knows, is not an easy text to ‘illustrate’—as the inadequate word goes—for it is essentially philosophical in nature, filled with complex and abstruse thoughts, with just a little bit of narrative in the beginning which establishes the context of this ‘song celestial’. All that most early manuscripts of the text might contain, therefore, is an image of the chariot in which Krishna, as the charioteer, is seen speaking to Arjuna on the battlefield; or, sometimes, one more image, that of Vishwa-rupa, the glorious Cosmic Form of himself that Krishna reveals to Arjuna in the Eleventh Chapter. However, in this volume, the editor and publisher draw upon a host of images that lead one into the visual context of each ‘teaching’. The reader might find himself unprepared for this, for here, spread over the pages, he would find Brahma seated on the Primal Lotus sprung from Vishnu’s navel, the great Ocean being churned by gods and demons, yogis withdrawn from the world, the sacred syllable Om encompassing in itself the highest of gods, sadhus performing penance, pilgrims on the move. But, slowly, through these, a world of spirit opens up.

The eye gets riveted at the same time to the range of images of Vishwa-rupa assembled here and keeps returning to them. The utterances in the text are maddeningly beautiful. “I am Time grown old,” the Lord says at one point. At another: “I am death the destroyer of all/ the source of what will be,/the feminine powers: fame, fortune, speech,/memory, intelligence, resolve, patience . . . ” It could not have been easy for the painters of the past to translate these sights or these words into images, but, as we see in this volume, each one made an attempt, each in his own manner.

This article has been republished as part of an ongoing series Art N Soul from The Tribune.