The Arab world has had trade relations with Kerala since time immemorial. It was the rare collection of spices and jewels as well as of hill products and animals, that drew the Arab traders to Kerala. Historians almost unanimously agree that Arab trade ships, from distant ports of the Red Sea and the Persian Bay, have been coming to the Malabar Coast since the early centuries of the first millennium BCE to acquire products like pepper and cardamom (Panikar 1957:52).

Kerala has always traded with the Arabs, more than with other nations. For centuries, only the Arabs knew of the trade routes to the Malabar Coast. In fact, they were the ones to have introduced the products of the region to Europeans; this is evident in the fact that Europeans still use the Arab terms for Indian products. For instance, it was the Arabic phrase ‘Tamar-Ind’ that later formed the English word ‘tamarind’. Similarly, the word ‘sandalwood’ was directly lifted from the Arabic ‘sandal’. Likewise, there are multitudes of Arabic words for these products which are in use even today.

Ports like Kodungallur, Kozhikode, Kannur and Kollam were among the most important trading centres of ancient Kerala. It was through these ports that Arab traders exchanged commodities brought in from the inland towns of the region. The tradesmen insisted upon living in the Malabar region for as long as it took to acquire the commodities that they required. Subsequently, as these Arabs stayed in Kerala for long periods of time, they naturally formed kinships and alliances with the natives, and soon marriages between these foreign traders and native women became customary. Such relationships were the basis for the cultural give and take that took place extensively in Kerala.

Islamic religion in Kerala

There are varying and conflicting opinions on the arrival of Islam in Kerala. Some believe that Islam had gained a presence in Kerala during the time of Prophet Muhammad himself (570–632 CE), and that the traders had spread their religion across the world since then. There is, nevertheless, tangible proof that Islam has been spreading in Kerala ever since the 7th century CE. In his work, the Tuhfat al-Mujahidin, Sheikh Zainuddin has intricately chronicled events such as the conversion of Cheraman Perumal to Islam, and the arrival at Kodungallur, with the Perumal’s letter, by a party consisting of Malik ibn Dinar, Sharaf ibn Malik, Malik ibn Habib, his wife Khumariya, their children and their followers. The king had greeted the group warmly, and allowed them to build a mosque in Kodungallur; it is now known to be the first-ever mosque to be constructed in India. Malik Dinar and his son-in-law Malik Habib soon headed north, and the others headed south, to spread the word of Islam; they established mosques in places like Barkur, Mangalapuram, Kasargod, Ezhimala, Shrikantapuram, Dharmadam, Pantalayani, Kollam and Chaliyam.

The Mappilas

The community that arose as a result of this Arab-Kerala friendship are known as the Mappilas; they have been in Kerala long before Islam had begun to spread in the state. Keralites who had a blood relation with foreigners were referred to as the Mappilas. 'Along with the Muslims, even the Christians and Jews in Kerala were referred to as Mappilas. The practice of using different terms for each religion, like Jonakamappila, Nasranimappila, and Joodamappila, is still familiar in Southern Kerala. It used to be common practice to refer to those who simply associated with foreign traders as Mappilas. As northern Kerala barely had a Christian or Jewish population, the phrase subsequently evolved to mean Muslims exclusively (M. Gangadharan 2004:11).'

The Arab traders generally stayed for three or four months in Kerala while they oversaw their business, and it was common practice for them to have affiliations with the local women during this time. The Arabs being the chief source of trade between the two countries, such affiliations were encouraged by the kings and local rulers of the region. A heterogeneous community was, therefore, formed due to this Arab-Kerala relationship—the Mappilas.

It was these Mappilas who had first accepted Islam, influenced by the teachings of the Arabian Prophet. There are multitudes of opinions and stances on the origins of the word ‘Mappila’. Shamsullah Khadiri opines that it’s an amalgamation of the two words ‘ma’ and ‘pilla’, and that it translates to ‘mother’s child’; A.P. Ibrahim Kunju, on the other hand, has argued that it’s an abbreviation of ‘maha pilla’, which, he claims, was a term of respect that the locals used to address the foreign traders. Balakrishnan Vallikkunnu, meanwhile, theorised that it’s a corruption of the term ‘maflah’, meaning farmer, and that it was utilised when the Arabs began to engage in agricultural activities. The ‘maha pilla’ theory has, so far, achieved more widespread acceptance than the others, and is endorsed by personalities such as William Logan and K.P. Padmanabha Menon.

Again, the term ‘mappila’ translates to ‘son-in-law’, in both Malayalam and Tamil. The locals began referring to them as Mappilas in this sense, as the foreign traders began marrying the local women. Even today, Malabari Muslims refer to grooms as ‘putiyappila’, blending the words ‘puthiya’ (new) and ‘mappila’.

Mappila culture

As Islam began gaining a dynamic presence, the Mappilas began integrating the religion into the traditional culture of Kerala. Thus a major give and take has happened in the rituals and ceremonies between Hindus and Muslims. This is apparent in the functions connected with the ceremonies of Sufi dargahs, which were directly linked to the local trade and agricultural practices of those times. For example, in nerchas, or local festivals, the practice of chenda melam (chenda performance) and prasadam (offering to gods) distribution is evidently influenced by Hindu rituals. Even the style of dikir dua is similar to the bhajan-kirtan performances at Hindu temples. Social perspective of Hindu and Muslim festivals are also the same. Thus, these ritual practices have succeeded in maintaining unity while retaining diversity in the belief systems.

A similarity can also be observed in the costume and colours of many art forms like Kathakali. The costumes of female performers of Kathakali resemble that of a Muslim woman. It is important to note that Mappila characters are found in many rituals in Kerala. For example, we can cite some Muslim characters in Theyyaattam, the main ritualistic art form of North Kerala. Alitheyyam, Mukritheyyam, Babriyan Neythiyar, etc. are some of the major Mappila Theyyams. The costumes of Mappila Theyyams are the same as that of Malabar Mappilas. Azaan calling and Niskaram are also part of the ritualistic traditions of Mappila Theyyams. There is similarity between the art forms of Kerala, and the architecture of Kerala as well. Kolkali of Mappilas is a variation of Kolattam and Koladipattu prevalent among the Nair women of Kerala. While the mischief of Lord Krishna was the plot of Kolattam, Mappilas used songs praising Allah and other prophets while performing Kolkali. Again, Parichamuttu of Mappilas is a variation of Hindu Parichakali. Thus, it may be said that it is the culmination of this give and take in rituals, traditions and art forms that have created a mixed culture for the Mappilas.

Mappila language

Mappila Malayalam is the variant of Malayalam adapted by the Mappilas for the day-to-day business of life. In historical documents and official records, Malabar Muslims are mentioned as Mappila Malayalees and their spoken script as Mappila Malayalam.

In addition to Malayalam, Mappila Malayalam is rich in vocabulary and expressions, and also has influences of languages such as Arabic, Persian, Urdu, Hindustani, Tamil, Kannada and Telugu. There are no hard and fast rules in the structure, grammar or choice of expressions in Mappila Malayalam. We can notice many expressions depicting the essential Muslim cultural identity of Kerala. It was not only a spoken script, but also a literary language. Several literary forms, both in spoken and written language, have originated in Mappila Malayalam.

Arabi Malayalam

Arabi Malayalam is the system of writing Malayalam language using the Arabic script. There are two main arguments on the origins of Arabi Malayalam; the first one claims that Arabi Malayalam was created by the Arabs themselves. One of the main reasons why the Arabs came to Kerala, apart from trade, of course, was to propagate their religion. However, both conducting their business and spreading Islam was impossible with the limited communication skills they had in Malayalam. A language, specifically for the purpose of introducing the locals to Islamic ideas and practices, thus became a necessity. The lack of a common language was causing a crisis. Another issue was the recitation of the Quran, for which the Arabic language was obligatory. Since many of the earliest Islamic rituals were conducted in the Arabic script, it soon became imperative that the Keralites be taught the script. Instead of the native script, the Arabs encouraged the use of the Arabic script to write the native language. This resulted in the tradition of using the Arabic script for a multitude of local languages. Arabi Tamil, Arabi Kannada, Arabi Bengali, Arabi Kashmiri, Arabi Turkistani, Arabi Barkuri (Badgali), Arabi Mali, Arabi Malaysia, Arabi Pashto, Hindustani, Farsi, Arabi Sindhi, Arabi Turki, Arabi Svisli (Svakhliya), Arabi Unthlus, Arabi Tashkent, etc. are examples of this phenomenon.

To aid communication and propagation of religion, writing foreign languages in the Arabic script was common in those times. O. Abu and C.K. Karim both advocate the theory that Arabi Malayalam was created by the Arabs (Abu 1970:21).

'In the former half of the 1st century AH, Muslims had started writing the regional languages of the countries that they had reached, as part of migration or for religious propagation, in the Arabic script; hence, it is quite natural to believe that when they reached Malabar in 9th century AD, they started writing their language in the Arabic script' (Jaleel 1989:279).

The second theory of origin claims that the Arabs didn’t deliberately create Arabi Malayalam at all, and that natives who knew the Arabic script gradually developed it after beginning to use it in their day-to-day lives. The Mappilas initially learned the Arabic script for religious reasons. They may have first used this system to record the religious aspects of their spoken language. In the early days, there was a feeling that it’s inappropriate to write the Quran or any other sacred texts, scriptures and hymns in any other script, because it was believed that the Arabic script had been bestowed by God. Because of this, the Muslims of Kerala were forced to develop a new script, and it is clear that the Arabi Malayalam script was an outcome of this. Modelled on the Arabic alphabet, it was given extra letters to make sure that it served both languages with ease. Like the Arabic script, this too is written from right to left.

Since Arabi Malayalam was a medium of expression designed for the cultural beliefs and notions of Muslims, it naturally acquired a stronger hold of Arabic and Persian vocabulary, in that the script doesn’t possess grammatical rules or structure, it is different from Malayalam. The system of writing foreign languages in Arabic alphabet was prevalent in Kerala even before the Muslim population had substantially increased to sustain a cultural identity of its own. Ever since AD 1206, since Qutb-ud-din Aibak had made Delhi his capital and had begun his rule, there had been Muslim rulers in India. Languages that use modified Arabic scripts, like Urdu and Persian, had become the Sultanate’s official languages. Although Kerala never came under the rule of the Sultan, the influence it had on North India subsequently began to sway Kerala as well. All the early works composed in Arabi Malayalam were all written in coastal areas like Thalasseri and Ponnani. Arabi Malayalam began attaining growth in the 18th and 19th centuries, when Islam began to spread into more inland areas.

We have, in front of us, the history of how Chera Tamizhu has evolved into an amalgamation of languages, Manipravalam, and modern Malayalam, due to the influence of brahminical hegemony. The language mix, which we call Urdu, is the result of Muslim power in North India.

The historical background for the origin and growth of Mappila Malayalam is the cultural leadership of Cheraman Perumal, who went to Mecca after converting to Islam, the Arakkal Dynasty, and Alimarakkar, who are the guardian figures of Malabar, along with the short lived rule of Tipu Sultan. (M. N. Karasseri 1978:5)

Sooranadu Kunjanpilla, who has conducted an in-depth study of both the history of Kerala and the development of literature in the mother tongue, says on the subject:

It is heard that there are thousands of published and unpublished prose and poetry works in Arabi Malayalam. During my Kerala journey, I’ve had man of them read out to me. There are books of high standards on all sciences, and dictionaries. If the successors of Arakkal Ali Raja of Kannur subsequently ruled Kerala, the accepted alphabet of Malayalam would have been Arabi Malayalam. (Yuvakeralam 2.3)

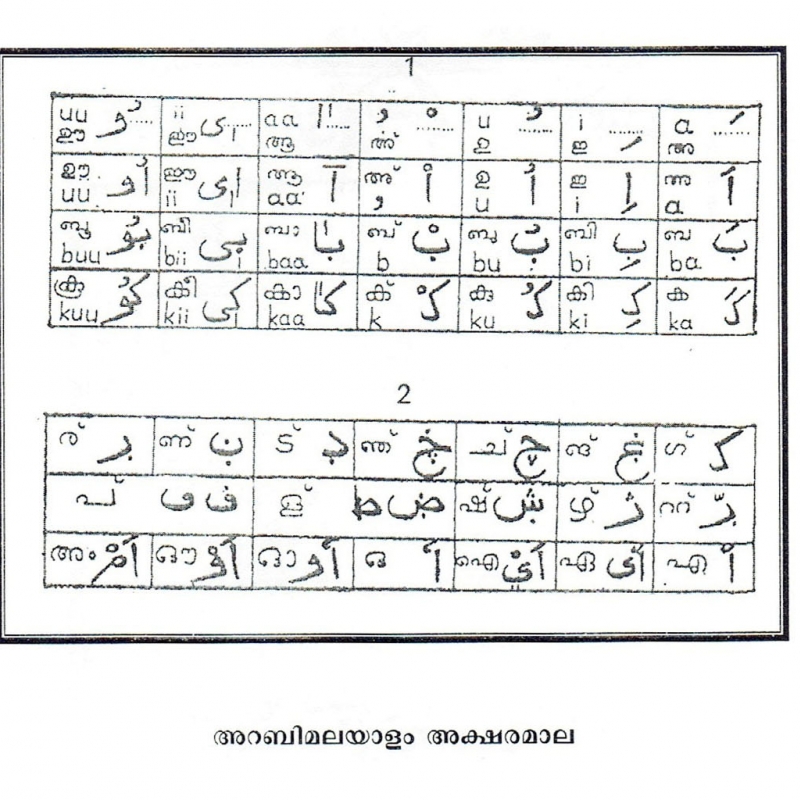

Upgradation of the Arabi Malayalam script

If we are to analyse early Arabi Malayalam books such as Vellattimas Ala and Niskarappattu, we can see that the Arabi Malayalam script of the time only had 35 letters. It may have been the first ever script to have been adapted and designed for the use of Malayalam. It was much more scientifically and popularly used, as compared to Vatteluttu and Koleluttu. Among the earliest reformers of the Arabi Malayalam script were Mamburam Sayyid Alavi Thangal, his son Sayyid Fadl Pookoya Thangal, their contemporaries and famous religious scholars like Valiyankode Umer Qazi and Avvakkoya Musliyar. In the first half of the 19th century, an Arabi Malayalam news magazine called Hidayathul Ikhvan was being published from Tirurangadi, whose owner was Mamburam Sayyid Abdulkoya Thangal. Thangal’s script upgradations were given a considerable boost by Master C. Syed Ali Kutty, who was among the most prominent reformers of the Kerala Muslims. He was a Mappila school inspector, and an accomplished scholar of Arabi Malayalam. Maulana Abdurahman Makhdum Thangal, Shujai Moythu Musliyar—author of Fathul Fattah (three volumes), complete abridged works of Faydul Hayat and Saphalamala epic (spiritual history)—and others played a major role in the upgradation of the Arabi Malayalam script. Sayyid Sanaulla Makti Thangal was another prominent figure here, and he wrote the Muallim ul Ikhvan. The upgradations quoted in this textbook were modelled on the Urdu script, due to which his work didn’t enjoy as much popularity as expected. Makti Thangal ran an Arabi Malayalam newspaper called Tuhfat Ul Akhyar Va Hidayathul Ashrar, which was published from Kochi for about a year; in this, he had employed the upgraded script he had quoted in the Muallim ul Ikhvan. Makthi Thangal’s friend Chennattuvalappil Haidero Subnu Abdurahiman, alias Adima Musliyar, wrote the Ikhrasul Inay Fi Sharhi Bidayathil, a work spanning more than 900 pages, and it was written in the likes of Makthi Thangal’s upgraded script.

It was Maulana Chalilakattu Kunjahmed Haji who upgraded the Arabi Malayalam script to suit modern Malayalam. He pointed out the shortcomings that prevailed in Makti Thangal’s version of the script. He wrote and printed the popularly accepted Arabi Malayalam alphabet, and in 1311 AH, created the first proper alphabet for the language. In 1912, Kunjahmed Haji himself wrote and published an upgraded version of the Arabi Malayalam alphabet, with indications to the mother tongue. Even during that time, from Alappuzha, Maulana Sulaiman Ubnu, Adam Musliyar and his disciple Vakkom Muhammad Abdul Khader had made efforts concerning the improvement of the Arabi Malayalam script. Nevertheless, it was Chalilakathu Kunjahmed Musliyar’s version of the script that the community eventually accepted and carried forward.

It was not just in script but also in sound that Arabi Malayalam had its distinctions. Only 15 Arabi Malayalam letters (a, ba, ta, ja, o, ra, sa, sha, ka, la, ma, na, ba, ha and ya) have equivalents in the Malayalam script; there are no unique sounds in Malayalam to pronounce the rest of the letters in the alphabet. For this reason, it’s incorrect to consider Arabi Malayalam as a variant form of the Malayalam script. Similarly, simply removing the Arabic vocabulary from the language won’t convert it into Malayalam. It’s impossible to deny that Arabi Malayalam is a language that was formed with importance given to the objective of improving communication between Malayalees and Arabs, and vice versa. Even before the Arabi Malayalam script had been formed, as a result of trade and other interactions, Arabic words had come into Malayalam, and vice versa. Arabi Malayalam is not a distinct, independent language from Malayalam. It’s only the script that is Arabic. When read, the sound and meaning is the same as Malayalam.

Arabi Malayalam writers

There were scores of Arabi Malayalam writers who gained prominence by their novelty and originality in their presentation and themes. Here, writers such as Khasi Muhammad, Kunjayin Musliyar, Mappila Aalim, Umar Labba, Manantekath Kunjikkoyathangal, Mundambra Unni Mammad, Chakkiri Moideen Kutty, M.A. Imbichi, Nallalam Biran, Naalakattu Kunji Moideen Kutty, Kunjiseetikkoya Thangal, P.T. Birankutty, Sujayi Moytu Musliyar, Icchamasthan, Mattungal Kunjikkoya, Chettuvay Pareekutty, C.A. Hassankutty, Pulikkottil Haider, Moyinkutty Vaidyar, K.N. Mammunji and Birankutty Musliyar deserve mention for their roles as creators of new writing techniques. Very few women writers have composed texts in Arabi Malayalam; some prominent names worthy of consideration are K. Aminakutty, P.K. Haleema, V. Ayeshakutty, and C.H. Kunjayesha. Among the more unique features of Arabi Malayalam are the clear and simple style of writing and a rural conversational vocabulary.

Arabi Malayalam literature

Considering the extremely limited usage of the language just three centuries earlier, it’s astonishing that by the 10th century AH, the popular usage of Arabi Malayalam had grown considerably compared to that of Malayalam. It was during this period that an explosion of literary creativity and imagination took place among the Muslims of Kerala, and this explosion created a vibrant intellectual society among them. New standards and values emerged in Kerala literature. The creative vision of the Mappila community reached its zenith in the 13th century AH. If one were to explore the motivating force of this vibrant creativity, one will reach events that have gone unrecorded in Kerala history and brings to light the history of Kerala Muslims in the 16th, 17th, 18th, and 19th century.

Considering Arabi Malayalam, a language that was formed with the aim of religious propagation, it’s natural that most texts composed in Arabi Malayalam revolve around themes of Islamic religion and history; non-religious texts are comparatively fewer in number. Once could say that virtually all Arabi Malayalam works were written with the intention of religious teaching kept in mind. In the initial stages, poetry was more popular, while prose began developing further on. Its prose was written in a simple, conversational style, in a way that seemed as if the author was speaking directly to the readers. However, there are very few original writings in Arabi Malayalam prose. Most of them are translations or adaptations of Arabic texts, but no work is a word-to-word translation. Instead of prose, they call it translation. For example, the independent work by Padoor Poyakutty Thangal is titled Baithullyam Tharjama (Baithullyam Translation). Original texts were often presented as translations to get credibility of religion and belief.

Arabi Malayalam prose can be divided into creative prose and scientific prose. Scientific literature includes religion, history, medicine, linguistics, astrology, astronomy, sex, interpretation of dreams and tantric texts. The main section under scientific literature includes translation of the Quran, Islamic laws, Islamic philosophy, texts on the science of action (Karma Shastra), etc. There are defined rituals and systems under Islamic worship practices, whose detailed accounts are given by Islamic texts on Karma Shastra. Islamic social laws are not discussed here. Instead, it’s all about the detailed explanations on the need for worship practices. Baithullyam, written by Padoor Koyakutty Thangal, is the most important text among this. Other texts that come under the same category are books written in Arabic, such as Humdathil Muzwallin, Riyalu Swalihin and Fathul Mu’in. Creative literature is comparatively less in Arabi Malayalam prose, but there are a few historical stories based on Islamic history, some translations of Persian and Arabic novels, and some small novels. Six years before Chandu Menon wrote Indulekha, Chahar Darvesh, the Persian novel written by Amir Khusrau in 1303 AH, was translated and published in Arabi Malayalam. There are about 50 novels, which are either translations or original, in Arabi Malayalam. Important among them are Umaraiyyar Kissa, Khamarussaman, Noor Jehan, Mantri Kumara Charitram, Amir Hamza (Five parts), Shamsussaman, Alfu Laila Laila (translation), Badarul Muneer Husnul Jamal (prose translation) and Kalsanobarod Enthu Cheythu. The novels like Khadeeja Kutty, by K.C. Komukkutty Maulvi, which was serialised in the Islam magazine Nisa ul Islam. Sainaba and Khider Nabiye Kanda Nafeesa by K.K. Muhammad Jamaluddin Maulvi Saheb and Subaida by Syedallavi Koya Thangal are on par with any modern novel.

A major share of Arabi Malayalam literature is poetry. They are unique in choice of words, theme and composition. There was a clear methodology involved. This poetic part can be classified as both scientific and creative. Scientific texts in poetry originated as a prerequisite for Islamic teachers, to introduce the dry prosaic texts to the general public. Most of these are religious texts, which include philosophy, belief systems and rituals. Some are history-based. Thus, Arabi Malayalam is rich in variety and mixed with many streams of thought and methodology.

Present state of Arabi Malayalam

Even after the Malayalam language has become more popular and Malayalam literature has a dominant presence, Arabi Malayalam continued as the literary language of Mappilas. But after the majority of the Muslim population advanced educationally, they started discussing the anomaly in continuing with the practice of writing Malayalam in the Arabic alphabet. Along with this, many Muslims have emerged who can write with finesse in Malayalam. There were also differences of opinion about the language style, and also about the selections of themes with Islamic foundation.

Some Islamic organisations started criticising the ideas and approaches in Maalappattu, and similar texts based on religious beliefs. They also criticised the ritualistic aspects of Nerchappattu. Such religious and educational reforms have led to a reduction in the practice of writing in Arabi Malayalam. Mappila writers have started writing in Malayalam. But the Sunni Muslims of Kerala still write and publish periodicals in Arabi Malayalam as part of their efforts to sustain this style of language. Some of the madrasa texts of Samastha Kerala Islamic Educational Board at Chelari in Malappuram, and part of the publication Al’mu’alleem are being published in Arabi Malayalam. Al’mu’alleem can be considered as the only publication in the modern times which publishes in Arabi Malayalam. Now the only link that the Muslims in Kerala have with Arabi Malayalam are the madrasa texts.

References

Abu O. 1970. Arabi Malayala Sahityacharitram. Kottayam: National Bookstall.

Gangadharan M. 2004. Mappila Padanangal. Kozhikode: Vachanam Books.

Jaleel K.A. 1989. Lipikalum Manavasamskaravum. Tiruvananthapuram: Kerala Bhasha Sahitya Institute.

Karasseri M.N. 1989. Works of Pulikkottil Hyder. Vandur: Mappila Kalasahityavedi.

Panikar K.M. 1957. Keralathinte Swathanthriyasamaram.