During the 1960s, Malayalam literature went through a major shift in sensibility. In reinventing itself from a new perspective, the Malayalam novel moved away from the ideological baggage of the earlier romantic-progressive phase. The realistic mode that had held sway over the narratives of Malayalam novels from the 1930s, now gave way to a more subtle and searching style that probed the complex inner worlds of characters. The massive social transformations that followed in the wake of social reforms and subaltern movements in the first half of the twentieth century had lost their immediacy by the time India became independent.

Post-colonial India had brought more anxieties than hopes, and in the emerging reality, Gandhian values rooted in asceticism and emancipation of the soul and the Nehruvian vision of a modern India were at odds with each other. A new generation of young writers in the 1950s, among whom the prominent ones were M.T. Vasudevan Nair, T. Padmanabhan, N.P. Muhammad and Madhavikutty (Kamala Das for English readers), scripted a new narrative about loss, alienation and disillusionment. Instead of hrepresenting the society in black-and-white terms with an accent on social change, they sought the hidden motives behind actions and explored the mindscapes of characters from a non-judgemental perspective. M.T. Vasudevan Nair and Kamala Das were pioneers in psychological realism, and did not subscribe to political stereotypes about social transformation. They were the precursors of the great modernists, who stormed into Malayalam fiction with an imaginative sweep and range that stunned the readers. O.V. Vijayan’s Khasakkinte Ithihasam (The Legends of Khassack), published in 1968, was a cultural event that altered the very grammar of narrative in Malayalam fiction.

The modernist novelists in Malayalam effected a clean break with the social realist mode and all that it stood for. They were sensitive to the changes sweeping the world. By 1956, the socialist dreams of a generation were deeply unsettled by the revelations of the purges of Stalin and the Soviet invasion of Hungary. Modernist writers were sceptical of ideological positions and found belief systems on the left and right equally bankrupt. In most of the modernist works of the 1960s and 70s we confront the lonely, disoriented young men haunted by a sense of the absurd as they feel trapped in their lives without any exit.

The existentialist literature of the post-World War Europe was a major influence in shaping their attitudes to life and society. But to characterise modernist Malayalam fiction as derivative would not do justice to the genuine sense of metaphysical unease these writers conveyed regarding the destiny of the modern man. Through emotionally charged narratives they opened up the world of the Malayali to horizons of experience that were universal and philosophical. Writers such as O.V. Vijayan, Anand, M. Mukundan, Kakkanadan, Punathil Kunhabdulla, Sethu and Methil Radhakrishnan brought Malayalam fiction closer to the international writing scene of the times. Their language was refreshingly free from sentimentality and pretentious verbalism. It often explored forbidden domains of experience, creating an ambience that was both innovative and experimental. What distinguished these writers was a concern with the human condition in the modern age, and a faith in the ability of art to confront the limits of language and imagination in representing the contingent and the contemporary. In the remaining part of this article I will discuss the works of Anand as a representative figure of modernist Malayalam fiction.

Fig. 1: Anand's parents

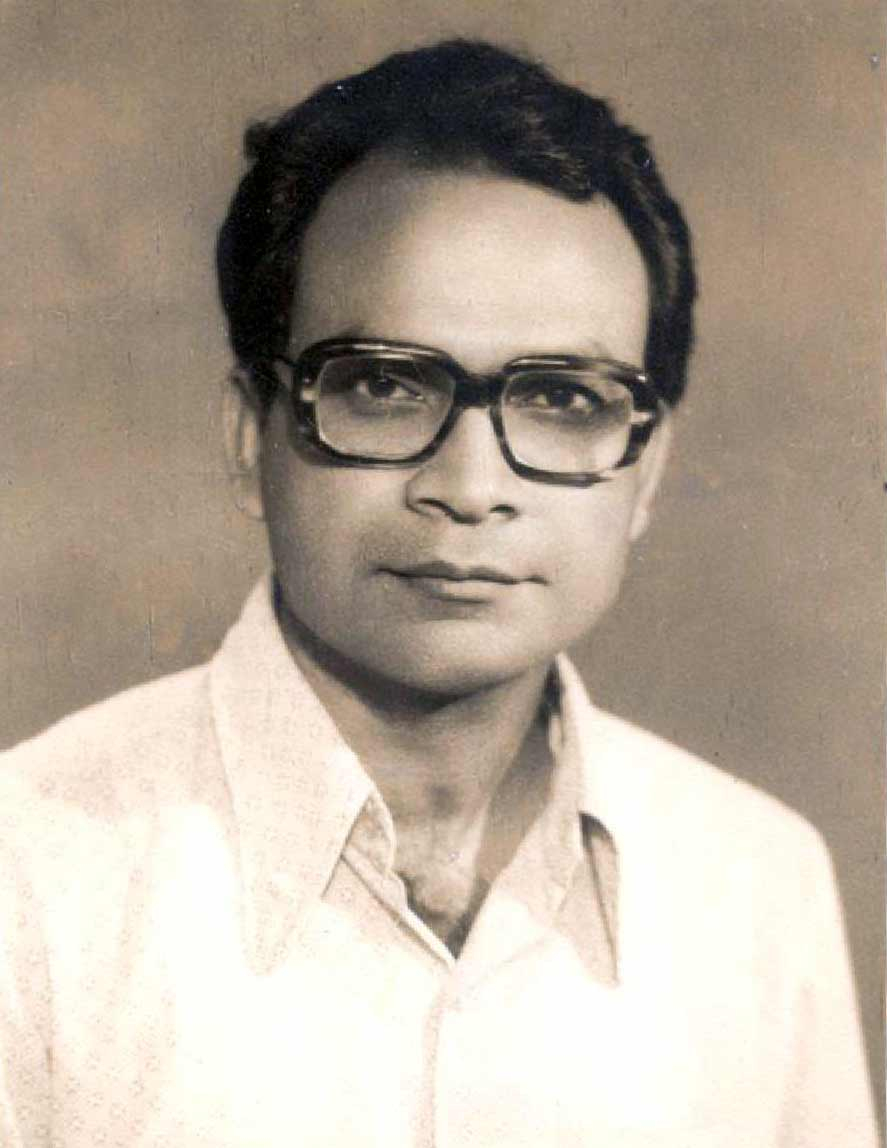

P. Satchidanandan, who writes under the pseudonym Anand, was born in 1936 in Irinjalakkuda in central Kerala, into a middle class family where his father was a school teacher. After graduating in Engineering, he served in central services till 1994, which included a four-year stint in the army. Having seen the length and breadth of India, particularly the Gangetic plains, in the years of its turmoil in the post-Nehruvian era, Anand’s major fictional works, set outside Kerala, consistently pursue issues and subjects related to India’s modernity. He is concerned with questions of social justice, limits of freedom, denial of equality and the subterfuges used by the nation state to conceal its ruthless acts of oppression in the name of democracy.

Apart from novels and short stories, he has published many essays where he debates contemporary issues related to communalism, relevance of Gandhism, decline of values in public life and the struggle for social justice and equality by marginalised sections of society. His role in clarifying the liberal positions against fundamentalism has been seminal in Kerala. What sets him apart from other modernist writers of his generation is the consistent intellectual strain in his work, with his novels and short stories grappling with questions of profound political and social significance.

The novel that launched Anand to the forefront of Malayalam modernist fiction was Alkoottam (The Crowd, 1970), which was widely acclaimed as a path-breaking work. Its narrative running over four hundred pages, set in Bombay, which represents a microcosm of India, covers the period between 1957 and 1962. Through the stories of Sunil, Joseph, Prem, Sundar, Lalitha, Radha and many other minor characters, Anand portrays the sense of oppression and aimlessness that afflicts the youth who feel trapped in the city with no exit in sight. Joseph’s love-hate relation with his family in Kerala evokes in him a helplessness that we also see in varying degrees in Sunil and Sundar. Joesph is not able to reciprocate Radha’s love just as Sunil and Lalitha are unable to bond with each other. The city of Bombay with its dehumanising environment fills them with a perennial sense of anguish. Nothing in their upbringing and culture had equipped them to cope with its corrosive violence.

Anand documents a particular phase in the socio-political history of modern India, when migration from the rural hinterlands to the cities had multiplied and cities had become the epicentres of a new street culture. The crowd of the title sums up Anand’s vision of modernity as a continuous state of agitation and a permanent condition of flux, with no redemptive vision regarding man’s ability to transcend himself through commitment to ideology or belief system. In this sense, Alkoottam is a statement about the loss of faith in the liberal humanist vision that animated much of our literary creation in the first part of the 20th century.

Fig. 2: Young Anand

Anand’s fictional works are characterised by a deep sense of history. He has been greatly influenced by the history of the Gangetic plains where saints, pilgrims and travellers traversed the land in search of solutions while marauding armies laid waste entire stretches of land, rendering people homeless. History is witness to the endless march of refugees, who were ordinary people uprooted from their homes and habitats. His novel Abhayarthikal (Refugees) is inspired by a panoramic vision of history as it unfolded in northern and north-eastern India. Characters such as Gautaman, Suman, Mahesh and Haridas are unable to locate a locus of meaning in the random events of the past. Missing people such as Suman, Arati and Sandhya were involved in quests for humanity in an oppressed world of exploitation. Anand shows how ideologies fail human beings who are in search of a hold on reality. From Buddhism to Gandhism, the teachings of saints have gone largely unheeded, as the country drifted into anarchy and violence. Anand constantly looks for continuities amidst disruptions of history as he is aware of the vitality of societies and their ability to reinvent themselves.

Anand feels that the moment of the nation state reconstitutes the relationship between the appearance and reality in the life of the nation. In his novels like Marubhoomikal Undakunnathu (Desert Shadows, 1989) he confronts a deep division at the very centre of the nationalist narrative, when institutions that were created for the welfare of the people turn predatory and oppressive. Kundan is a labour officer at the Rambhagarh Strategic Installations Project, which is shrouded in mystery. He finds that most of the workers are condemned prisoners. Suleiman is serving a prison term for Pashupati Singh, who is influential and affluent. Suleiman’s family is paid a meagre sum for his ‘service’ but he is dependent on that as the only means of survival.

The villages around Rambhagarh have not changed in centuries. The people are mired in poverty, disease and illiteracy. Drought, starvation and migration haunt every generation. Rambhagarh has been in a permanent state of siege over centuries. The very mention of ‘sarkar’ invokes terror though it is meant to enforce law and order. Anand shows how the nation state has turned into an endless Kafkaesque labyrinth. Kundan’s attempts to save some of those trapped around him makes him a suspect, and finally he is forced to flee from the project. By this time Suleiman is killed in an accident, and Bhola, whom he had tried to help, dies in a riot.

In the city, Kundan finds that no editor is ready to publish the harsh truths about the ‘sarkar’. Kundan starts doubting whether he is a crusader or a refugee. He cannot find any pattern or design in the elaborate subterfuges that have become the hallmarks of the nation state. He tells himself: ‘Rational minds should know that a big unreason which neutralises all reason lurks behind everything, under our chairs, below the bed and under our feet’ (Anand 1998:246).

For Kundan, the dream of a nation state that guarantees social justice and liberty turns into a nightmare when he learns that blind loyalty is the price one pays for the membership in the system. He comments: ‘Civilization was accountability, Ruth had once told Kundan who had countered it by saying that it was mere accounting’ (Anand 1998:249). Anand’s portrayal of India is an allegorical mapping of post-colonial societies across the world that are unable to create a just social order after getting independence from colonial powers.

As mentioned above, Anand is a thinker who shapes his fictional narratives out of his engagement with the world of ideas. In his award-winning book Jaiva Manushyan (Organic Man, 1991) he traces the trajectory of man’s ascent from savagery to culture through many stages of complex social and cultural organisations. In the chapter on ‘The Organic Nature of Man’s Freedom’ he argues that man is separate from nature, while being a part of it. This is what makes his quest for freedom a condition of his existence as well as an impossibility. Man is able to explore and discover the laws of nature, even as he is part of the very same nature. In this sense, nature becomes aware of itself through man. What distinguishes man is the power of intellect, will and imagination. While other animals could not evolve beyond the state of instinct, man moved beyond the savage state of nature through social organisation and evolved further to another stage through the creation of culture. This stage of individuality forces him to live in a state of paradox since he is a product of society and cannot completely transcend his own social self.

In the essay ‘The Country and the City’ he shows how the rise of cities led to division of labour. While villages largely remain static, cities tend to become complex organisations as the seat of human culture and intellect. Education, art, culture, literature and entertainment flourish in the cities. When the contradictions between the villages and the cities deepen they may lead to revolts and realignment of power centres. There has been a rise and fall of urban civilisations many times in history. Anand says that modern urban civilisation has generated a widening gap between the ruling class and the working class consisting of peasants and workers. The ruling class, with the help of science and technology imposes a social structure above to sustain its own interests. The hierarchical and artificial structure of power concentrated in the cities is insensitive to the real needs of the downtrodden and the marginalised.

Thus, today man is being oppressed by the very products of his intelligence and imagination. The colossal metropolis, as well as the highly centralised powers of the governments, fills modern man with an inertia and passivity bordering on numbness and passivity as he is unable to resist their overarching structures of authority. Anand feels that the solution will emerge only through a rational analysis of the problems and collective will of humanity. In Anand’s novelistic imagination, history is seen as a nightmare where human beings are seen as collectives of refugees perennially on the move seeking shelter from repressive regimes and authoritarian ideologies. Visionaries such as Buddha and Gandhi did make a difference to their quest but did not create a stable social order of justice, freedom and equality. Anand has repeatedly returned to the riddle of the failure of Gandhism in modern India. For him the inability of Indians to understand Gandhi and translate his ideas into social and political reality constitutes the greatest tragedy of modern India.

Fig. 3: Young Anand at his desk

Govardhante Yatrakal (Govardhan’s Travels, 1995) is one of the best-known novels of Anand. The quest for justice becomes central to this complex, self-reflexive narrative, which has for its central character Govardhan, who is taken from Bharatendu Harischandra’s political satire Andheri Nagari, Chaupat Raja (Dark is the County, Insane is the King, 1881). Anand says that he was deeply moved by this play which is a farce on the legal system of India. In the play Govardhan is sentenced to death only because the real culprit’s neck does not fit the size of the noose.

The novel begins when Bharatendu enters the prison cell of Govardhan and releases him. Govardhan appears before Ramachandra, the mathematician, to ask him whether whatever is happening is right or wrong. The man of logic is taken aback at the irrationality of injustice and soon leaves his enquiries into science to pursue moral questions of greater urgency. Now Govardhan wanders distraught and desolate, the noose still hanging above his head. Among the people he meets in the novel are Ibn Battuta (1304–1368), Galileo Galilei (1564–1642), Sankaracharya (early 8th century), Thyagaraja (1767–1847), Humayun (1508–1556), and Shah Jahan (1592–1668). All of them give their versions of man’s quest for truth and justice. Govardhan receives no clear answers for the enigma of injustice in the world. Still he explores the possibility of freedom and justice. There are many others from history, mythology and fiction, such as Chitragupta, Mirza Galib, Umrao Jaan, Kalidasa, Kepler, Satyakama and Gautama Buddha in the digressive narrative.

In his wanderings Govardhan finds cities and villages ravaged by atrocities and brutalities and people condemned to endless suffering without any respite. In one village, he finds the weavers who had protested against colonial oppression by cutting off their thumbs. Ramachandra says at one point: ‘The most important thing is to know the pain of the injured and the suffocation of the helpless’ (35). Govardhan’s wife is arrested and daughter is kidnapped. Ali Dost, the brother of Govardhan who got separated from him, becomes a tormentor of people, carrying out the punishment pronounced by kings and sultans. He tells an old woman later in the novel, ‘I am only a slave, have no fear of pap-punya. Even my victims will not hate me’ (71). Kamran Mirza, the brother of Humayun, was blinded by him. For Humayun to ascend the throne, all the contenders of the throne had to be executed or banished. This struggle for power repeats endlessly in many forms through history, regardless of the suffering caused to the common people.

Govardhan is the eternal victim who can be seen in all ages and countries irrespective of the nature of politics or religion. At one point Bharatendu tells Ibn Battuta: ‘The farces we write turn into tragedies without our own knowledge’ (58). It is impossible to summarise the complex narrative that branches out in different directions into history, politics and mythology to return repeatedly to the central question of liberation of man. These words of Gautama may be taken as something of a moment of epiphany for Govardhan’s endless agonising quest for justice: ‘We should search for liberation from fear and sorrow. That cannot be achieved by rejecting our body or our neighbours. We have to realise our freedom in our own body and our neighbours. We have to carry the four-limbed cross of our existence. We have to be crucified on its limbs. We have to writhe in pain on the cross, before resurrecting ourselves from it’ (263). Anand writes in his preface to the novel: ‘A society which is not inflamed by a passion for justice, will be lost to time’ (7).

Anand uses the word ‘poromboke’ to suggest those sections of people who are on the margins of society without any access to basic needs. Every nation state produces its own ‘poromboke’. He comments in his Marubhoomikal: ‘In reality, the state functions as an anti-state. An anti-state constituted by the anti-social within society’ (Anand 1998:200). Anand’s novels explore those marginal people and their struggle for survival as they fight the system for a place in the sunlight. This is true of his Apariharikkapetta Daivagal (Stolen Gods, 2001) and Vibhajanangal (Partitions, 2006); both these novels continue Anand’s meditations on the contradictions of contemporary Indian society as seen through certain sensitive characters searching for answers in a labyrinthine world of abject powerlessness and destitution. Vibhajanagal is more of a travelogue by the author through various parts of India, highlighting issues and problems that do not figure in the mainstream media of literary works.

A significant work of fiction by Anand that dates back to the 1990s is Vyasanum Vighneswaranum (Vyasa and Vigneshwara, 1996), which is postmodern in its approach to questions of time and history. The two sections of the novella are called ‘Kriti’ (Text) and ‘Kalam’ (Time). Anand comments at the beginning of this book: ‘When smirthi, what is remembered, and shruthi, what is heard, get subsumed in vismruthi, amnesia or oblivion, and further by mrithi, death, krithi, text alone remains’ (Anand 2000:21).

The central figure that runs through ‘Kriti’ is that of Eklavya, the forest dweller who was punished by Drona, a Brahmin guru, for excelling in the art of archery. Drona asked him to sacrifice his thumb, as his gift to him, and Eklavya obeyed him without protest. This helped Arjuna, the great warrior prince of the Mahabharata, to remain invincible in the art of archery. However, in the story narrated by Anand, we come across a text called Nishadpurana, which recounts a long conversation between Eklavya and Abhimanyu, Arjuna’s son.

The story recounts the author’s search for Nishadpurana through many years of his journeys. When he finally chances upon the book in a library in Delhi, he finds that a crucial part of the dialogue dealing with Eklavya’s death was missing. The second part of the novel also deals with a missing text. The narrator meets an activist in one of his long distance railway journeys. He is obviously a rebel on the run. They discuss what befell ancient kingdoms such as Vaishali, Kosala and Magadh. He gives the author an unfinished play titled Nagaravadhu (The Bride of the City) which is about Amrapali who is forced to become the Nagaravadhu through a democratic process devised by the wise people of Vaishali. In the words of Amarasena we have the central argument of the story: ‘Listen, you selfish and greedy people, society is the soil, from which germinate fine, dignified people. But you, you fear such people. You mow them to the ground, then you make them the pillars that bear weight of the edifice of a decadent civilization which you yourself have constructed’ (Anand 2000:104–5). Anand shows how knowledge cannot liberate us as it is mediated through discourses and institutions that partake of repressive ideologies. This is why Anand quotes from a book titled The History of Torture towards the end of the book: ‘Torture is ubiquitous. At times, it is inflicted on the faithful, at other times, on those who question faith, and yet other times, who are neither’ (Anand 2000:122).

Anand’s short stories also tend to be cerebral, presenting an argument and a vision through a human situation. Stories such as ‘Nalamathe Aani’, ‘Aaramathe Viral’, ‘Kabaadi’ and ‘Keetakosham’ are outstanding stories that leave a deep impression on the mind with their emotional rigour. A story such as ‘Nalamathe Aani’ (The Fourth Nail) shows how Anand rewrites an internationally known tale about the Romany blacksmith who forged three nails to crucify Christ. Many versions of this story exist, but Anand’s version emphasises the relations between society and individual, morality and institutions, and religion and justice. Here the soldiers who went in search of a blacksmith to forge the four nails for crucifixion squandered their money on drinks and could not get a blacksmith for what money was left with them. Finally, they found a gypsy blacksmith who would only make three nails for the amount they gave. The soldiers who were to crucify Christ found the nails insufficient to complete their work and let Christ go. When he returns to his disciples they do not recognise him. They have no use for a Christ who was not crucified. The blacksmith who had forged the three nails discovered that he was responsible for the crucifixion in an indirect way and had become a wanderer with an unsettled mind. Christ goes in search of the blacksmith who made the three nails for his crucifixion. The story ends in their meeting, which is charged with an epiphany of understanding.

Anand’s works have been characterised by intellectual rigour and deep human concern for humanity as a whole. No writer in recent times has pursued these themes with such consistency. Though he addresses Malayalam readers in his fictional works, his novels and stories are rarely set in Kerala. Most of his characters cannot be traced to any caste or locality by their names. His works transcend the narrow boundaries of region and religion to represent the major socio-political issues of the subcontinent, creating a framework of ethical imperatives that critique and evaluate our sensitivity and conscience. His thematic range shows a deep sense of history and an equally strong commitment to egalitarian values. His narratives are haunted by a profound sense of disquiet. One can dispute his macro-views for lack of attention to details, particularly when it comes to his depiction of a revisionist view of the past, but there is no gainsaying the fact that he has, over the years, created a body of work that puts the embattled state of Indian society at the very centre of an imaginative universe.

Note: Unless otherwise mentioned, the translations in the article are by the present author.

References

Anand. 1998. Desert Shadows. Translated by K.M. Sherrif. New Delhi: Penguin.

Anand. 2000. Vyasa and Vigneswara. Translated by Saji Mathew. New Delhi: Katha.