To gain comprehensive understanding of the art of Ajrakh, I held lengthy discussions with Khalid Ameen Khatri and Ameen Ibrahim Khatri from Ajrakhpur in Kutch, Gujarat, as well as Pukhraj Kastur Chand Khatri, Kanhaiya Lal and Bakhar Singh Khatri from Barmer, Rajasthan. I have further included reference material from Dr. Lotika Varadarajan’s book Ajrakh and Related Techniques, Noorjehan Bilgrami’s Sindh Jo Ajrak and Françoise Cousin’s ‘Light and Shade, Blue and Red: The Azrak of Sind’.

One of the biggest questions around Ajrakh is how best to define it? Is it a technique of cloth printing, a special kind of design composition or a type of attire? The other question is regarding the origins of its name: does it emerge from Arabic, Sindhi or Sanskrit?

This much is certain, that in the Indian subcontinent, during the period of the Harappan civilization, the settlements along the banks of the Indus River had developed the art of weaving cloth as well as decorating it through techniques such as dyeing and printing. Along with black and red, it was principally blue printed attire that was extensively used. According to Noorjehan Bilgrami, the design found on an Indus Valley figure depicting an ascetic is used in Ajrakh prints even today. Presently, the design is known as ‘Kakad’, which means cloud. This continuity of design exhibits the ancientness of the Ajrakh printing tradition.

In the 7th century BCE when the Iranian and Arab armies reached the Indus region they were attracted to these printed cloths. Since in Arabic the colour blue is referred to as ‘Ajrak’, it is possible that they would name the predominantly blue cloths as ‘Ajrak’. It seems that over time the word morphed from ‘Ajrak’ to ‘Ajrakh’, which in modern-day Sindhi means ‘leave it for today’. A saying which emerged from this translation is that Ajrakh printing is such laborious work that the artisans would say, ‘Aaj rakh do (Let this be for today),’ we will do it later. This is another possible reason the material is known as Ajrakh.

The fascinating fact here is that this one difference in the last letter of the word, from ‘k’ to ‘kh’, changes both the language of the word as well as its meaning. Ajrak is linked to the ancient Arabic language, Ajrakh to present-day Sindhi. Another notable fact is that the Sindhi alphabet too is similar to Arabic and Farsi. An additional point of interest in relation to the word’s origins is that the first time there is mention of this cloth being referred to as ‘Ujruk’ was in 1669 at a display in Karachi, Pakistan. Today, these uniquely printed cloths are renowned the world over as Ajrak/Ajrakh.

In common parlance Ajrakh refers to the exquisitely designed, brilliantly dyed and skilfully printed multipurpose cloths that are used chiefly by men. The cloth was most popular in the Sindh province and today it has become an integral part of Sindh (Pakistan) pride and culture. It continues to be used for all kinds of attire such as sarongs, plaids, turbans, shawls, cummerbunds, etc. It was in vogue along both sides of the Indus River in pre-Partition India—being mainly used by Sindhi Muslim animal-keepers from Sindh (Pakistan), Kutch (Gujarat) and Marwar (Rajasthan).

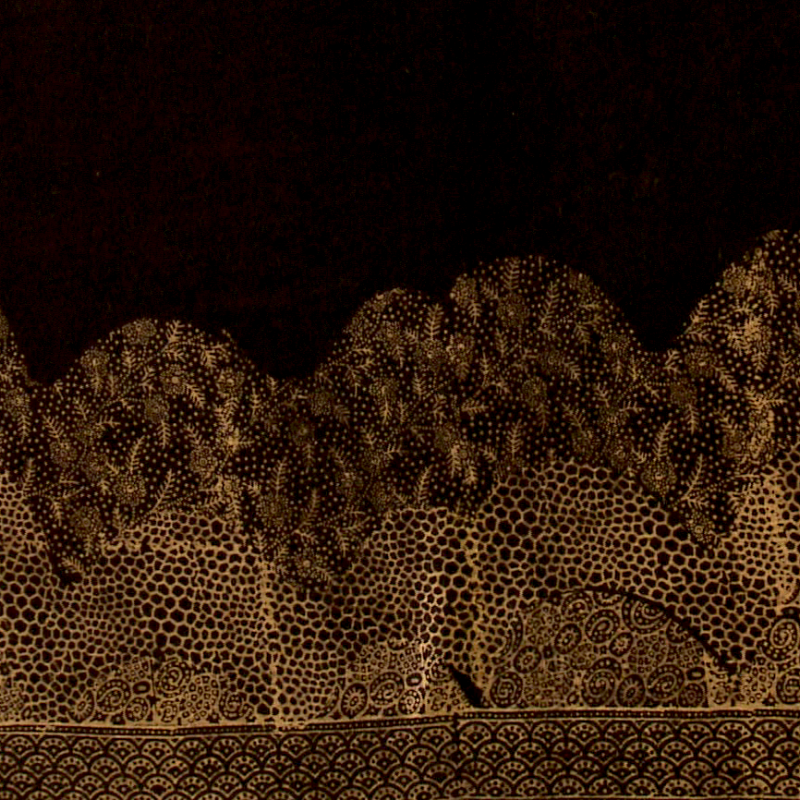

Various stages of Ajrakh making Courtesy: Crafts Museum, Delhi

Traditionally, Ajrakh material is made by men using the system of resist-dyeing with natural colours, which are printed on one or both sides of the cloth. Generally, the width of the cloth is 1 metre, while its length is 2.5 metres. The printing technique follows an ancient and fascinating system. Both ends of the cloth are decorated while three sides have embellished borders, whose designs are fixed. Only the motif in the centre of the cloth may be changed. To make a sarong, two turban cloths with borders on three sides are joined in such a way that the final sarong will have a border on all four sides.

Ajrakh printing is an ancient artistic tradition, whose development has seen the contribution of many cultures, which is apparent from the prevalent designs. According to Françoise Cousin many of the Ajrakh designs have Iranian/Islamic influences, evident from their geometry and symmetry. Dr. Lotika Varadarajan has elaborated on the imprint of the Sufi philosophy on the craft. Characteristics of Ajrakh such as its geometric designs and names such as ‘riyal’ and ‘ishq painch’ reflect the Arabic-Farsi influences.

One of Ajrakh’s most distinguishing qualities is that it is one of those art and craft traditions that have kept alive its traditional character through the challenging period of modernisation, and the craft’s established producers as well as customers still remain loyal to the craft.

The art is said to have originated in the 16th century CE, on this side of the Indus River, where the Thar Desert spreads across the regions in Gujarat and Rajasthan bordering Pakistan. The erstwhile ruler of Kutch Rao Bharmalji – I (1586–1631), invited the cloth-printing Khatri artisans from Sindh and gave them permission to settle and earn their livelihoods anywhere in Kutch. They were given land by the state as well spared any taxation on their produce. Over time, the villages of Dhamadka and Khavda in Kutch became the primary centres of the craft, followed by Barmer in Rajasthan, which too became recognised as an important centre. Most of the artisans of Kutch and Barmer believe that their ancestors were from Sindh, and even now many of their relatives live in the Sindh region.

The traditional purchasers of Ajrakh were Muslim nomadic animal-keepers, a group that still survives. In Kutch (Gujarat) this community is referred to as Maldharis. In Marwar (Rajasthan) the community is known as Muslim Patels and their hereditary occupation is that of cattle-herders. In Barmer, Ajrakh is used by the Muslim potter community as well. The traditional attire, worn casually earlier but now used mostly for weddings and other special occasions, consists of two pieces of cloth—a sarong and a turban. The sarong is topped by a plain kurta (tunic) and the turban is tied on the head.

These days the Khatri artisans of Kutch have almost stopped producing Ajrakh prints for their traditional Maldhari customers, because of the entry of screen-printed material using chemical dyes, mostly from Pakistan and locally from the village of Khavda in Kutch, which due to their low prices have become very popular. In 2001, an earthquake which caused severe damage in Kutch almost destroyed the village of Dhamadka. The Khatri cloth-printing artisans with governmental and social support established a new centre for cloth-printing called Ajrakhpur. Here, with the help of designers, voluntary organisations and businesspeople its contemporary form is being developed, which is gaining popularity among the urban elite.

Ajrakh production using screen-printing is taking place in Barmer, Rajasthan as well, but here the traditional production method still partly survives. According to a master-artisan Pukhraj Khatri in Barmer alone approximately seven cloth bundles (around 7000-1000 sarongs and turbans) are printed for traditional consumers of pure Ajrakh. The social as well as lifestyle changes in the Patel-community Sindhi cattleherders have reduced the hereditary use of Ajrakh considerably. In the 1970s, about 40 to 50 Khatri families were involved in Ajrakh printing, whereas today the number has reduced to just five or six families involved in the craft and that too part-time. While in 1975 the value of an Ajrakh piece was Rs. 7, today it ranges from Rs. 1000-1500.

From a technical perspective, Ajrakh is a very demanding and laborious form of cloth-printing and resist dyeing. To get the desired result from the resist dyeing, lime is used as an adhesive, which is an indicator of the special skills of the artisan. Ajrakh designs, in terms of variety and arrangments, are limited. However, the Ajrakh cloths, evenly printed on both sides, display the pinnacle of achievement in printing.

Today, in Kutch as well as Barmer, Ajrakh designs and techniques are being used even for contemporary fashion-wear. Therefore, the development of traditional Ajrakh printing as well as its popularity seems to have a promising future.