In 1897, Bal Gangadhar Tilak, known for his criticism of the British, was charged under Section 124A for his views in Kesari. On Tilak’s 100th death anniversary, Sahapedia analyses how this was an important moment in India’s political history as it marked the criminalisation of dissent in the grand spectacle of a political trial, setting the pattern for legal engagement with discursive violence in the years to come. (Photo courtesy: Wikimedia Commons)

Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) states, ‘Whoever, by words, either spoken or written, or by signs, or by visible representation, or otherwise, brings or attempts to bring into hatred or contempt, or excites or attempts to excite disaffection towards the Government shall be punishable with Life Imprisonment’.[1]

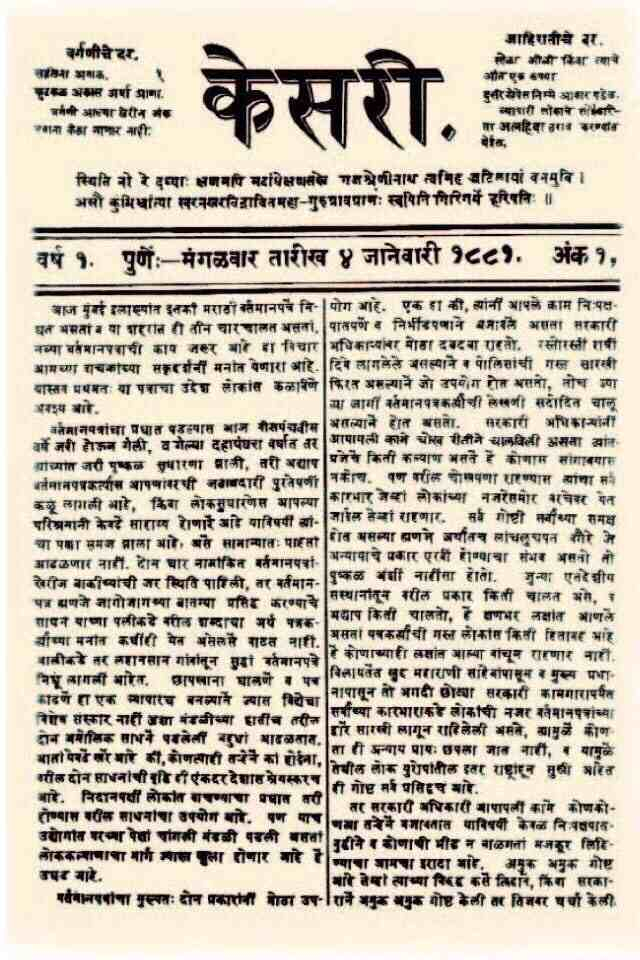

This wide and capacious section is called the law of Sedition—included in the IPC in 1870—and was used to try many freedom fighters, including Mahatma Gandhi. In 1897, Bal Gangadhar Tilak, known for his criticism of the British, was charged under Section 124A for his views in Kesari, his Marathi-language newspaper. This was an important moment in India’s political history as it marked the criminalisation of dissent as a grand spectacle of a political trial, narrativised by the press across British India.[2] More importantly, it set the pattern for legal engagement with discursive violence in the years to come.

Theatres of Trial

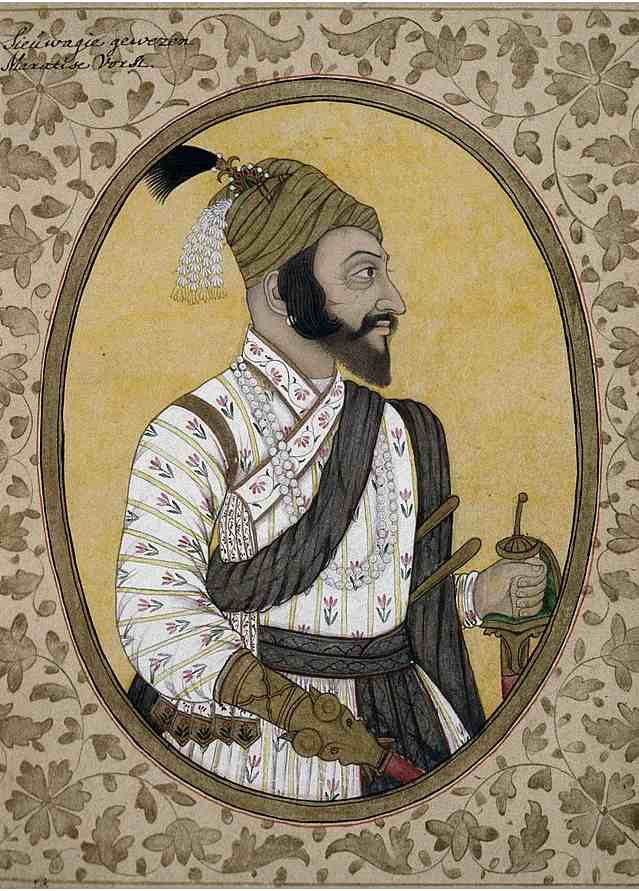

Tilak was charged for the publication of two texts—‘Shivaji’s Utterances’, a poem authored under an alias, and an unsigned report on the June 1897 Shivaji festival, at which Tilak and C.G. Bhanu, a notable Pune intellectual, spoke. This, the Bombay government claimed, incited ‘disaffection’ against the regime.[3] The prosecution was probably prompted by the assassination of officers W.C. Rand and Charles Ayerst shortly after the festival.[4]

Also read | Tagore and Caste: From Brahmacharyasram to Swadeshi Movement (1901–07)

In the courtroom drama that followed, the prosecution’s narrow legal interpretation simply reduced the texts to ‘incitement of feelings of “disaffection”’. On their intent as political critique,[5] the prosecutor said: ‘It is not a question which has anything to do with the case. The question for your consideration. . . is whether these articles are calculated to excite disaffection of the Government’.[6] In the press, on the other hand, the spectacle of the trial itself upstaged the texts.[7] After six days of litigation, the jury announced Tilak guilty and sentenced him to 18 months in prison.

A careful perusal of the two texts, however, illuminates Tilak’s political thought—as he stood on the radical side of liberalism—which is relevant for studying anti-state violence in modern Indian thought.

The Texts that Triggered ‘Disaffection’

At the 1897 Shivaji festival, Prof. Bhanu of Fergusson College had delivered a lecture on the illustrious career of the eponymous Maratha king. He highlighted Shivaji’s killing of Afzal Khan, the General of Bijapur Sultanate, in 1659. Historically, the subject had been mired in controversy. Had Shivaji struck the first blow? Was it a premeditated murder, and, therefore, unethical? Tilak’s address responded to this dilemma:

‘Was this act of the Maharaja good or bad? The question . . . should not be viewed from the standpoint of even the Penal Code or even the smritis of Manu or Yagnavalkhya or even the principles of morality laid down by the western and eastern ethical systems . . . Great men are above the common principles of morality . . . Did Shivaji commit a sin in killing Afzulkhan, or how? The answer to this question can be found in the Mahabharata itself. Srimad Krisna’s advice in the Gita is to kill even our teachers and our kinsmen. No blame attaches to any person if he is doing deeds without being actuated by a desire to reap the fruit of his deeds . . . Do not circumscribe your vision like a frog in the well; get out of the Penal Code, enter into the extremely high atmosphere of Srimad Bhagavadgita and then consider the actions of great men.’ [8]

Bhanu suggested that Shivaji’s actions were excusable given the context of a depraved, decaying government in Bijapur.[9] Following the example of their historical hero then, Tilak offered people the morality of the Bhagwad Gita to justify their own political actions undertaken for the national community.[10] Creating a complex philosophy of political action, Tilak articulates ‘a bold refusal of the political abjection enforced by colonial law,’ according to scholar Sukeshi Kamra.[11] He lays claim to an indigenous tradition of revolutionary thought, albeit Hindu, and underscores its singular virtue in accounting for their past and present action.[12] ‘Shivaji’s Utterances’ drew on similar tropes to compare a valiant past with their vanquished present.[13]

Also read | Do You Know About Chhattisgarh’s Jal Satyagraha?

Aside from the Gita and his Maharashtrian traditions, Tilak alluded to other stories of violent rupture. His analogies exposed the hypocrisies of the colonial government: in Europe, the actions of Caesar, Napoleon and French revolutionaries were seen as necessary agents of progress whereas the native subject’s radicalism, in India, was reduced to mere savagery; a sign of his primitiveness.[14] Later, in 1908, Tilak would also refer to the violent revolt against Charles I in seventeenth-century England. For him, it was a quintessential example of violence to replace a despotic ruler with constitutional, representative self-rule.[15]

No Boundary Between Physical Violence and its Discourse

Tilak’s 1897 trial offers an important example of the success of a local government in convicting the Indian press, in this case the Kesari, under Section 124A. It anchored the view that discursive violence was, in fact, an offence with criminal bearings. It also established that a purely discursive determination of militancy was sufficient for the law.[16] After all, Tilak was never caught in a physical act of violence or even found to have any links with the revolutionaries. In the ensuing decades, several nationalists would be charged with sedition; with or without any mention of violent vocabularies.[17]

Interestingly, the birth of the postcolonial independent state was characterised by more continuities than departures. The modern Indian State, according to scholar Swati Parashar, ‘shares purpose and methods of counterinsurgency and policing unruly bodies and marginalised subjects with its colonial predecessors.’[18] It even uses ‘the same idioms and justifications that mark epistemic and physical violence against the third world’ to legitimise its response to dissident citizens.[19] In a recent example, as reported by The Caravan magazine, Hany Babu, a Delhi University professor, was arrested in July 2020; making him the 12th public intellectual to be incarcerated in a string of arrests related to the Bhima Koregaon Elgar Parishad case. The police have made many claims, not least that the poets, writers, and academics arrested had been involved in a grand scheme of assassinating the PM.[20]

This increasingly defensive state, desperate to suppress any force of transformation in order to retain its power,[21] says Parashar, ‘is a reminder of colonial legacies and continuities that (re)produce hierarchical citizen subjectivities’ in the postcolonial world.[22] Who would have thought that Tilak’s 1897 trial would retain such acute relevance in the modern context, but so it is.

This article was also published on The Wire.

Notes

[1] Section 124A, Sedition, Indiacode.nic.in. Accessed July 30, 2020, https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?actid=AC_CEN_5_23_00037_186045_1523266765688§ionId=45863§ionno=124A&orderno=133.

[2] Sukeshi Kamra, ‘Law and Radical Rhetoric in British India: The 1897 Trial of Bal Gangadhar Tilak,’ South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies 39, no. 3 (2016): 546-559. DOI: 10.1080/00856401.2016.1196529

[3] Ibid.

[4] Robert E. Upton, ‘Take out a thorn with a thorn’: B.G. Tilak’s legitimization of political violence,’ Global Intellectual History 2, no. 3 (2017): 329-349. DOI: 10.1080/23801883.2017.1370240

[5] Sukeshi Kamra, ‘Law and Radical Rhetoric in British India: The 1897 Trial of Bal Gangadhar Tilak,’ South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies 39, no. 3 (2016): 546-559. DOI: 10.1080/00856401.2016.1196529

[6] Bal Gangadhar Tilak, S.S. Setlur, K.G. Deshpande, ‘A Full and Authentic Report of the Trial of the Hon’ble Mr. Bal Gangadhar Tilak,’ at the fourth criminal sessions 1897 of the Bombay High Court before the Hon'ble Justice Strachey and a special Jury.

[7] Sukeshi Kamra, ‘Law and Radical Rhetoric in British India: The 1897 Trial of Bal Gangadhar Tilak,’ South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies 39, no. 3 (2016): 546-559. DOI: 10.1080/00856401.2016.1196529

[8] Kesari, June 15, 1897, 3, quoted from Robert E. Upton (2017). ‘Take out a thorn with a thorn’: B. G. Tilak’s legitimization of political violence’, Global Intellectual History, 2:3, 329-349, DOI: 10.1080/23801883.2017.1370240

[9] Robert E. Upton, ‘Take out a thorn with a thorn’: B.G. Tilak’s legitimization of political violence,’ Global Intellectual History 2, no. 3 (2017): 329-349. DOI: 10.1080/23801883.2017.1370240

[10] Ibid.

[11] Sukeshi Kamra, ‘Law and Radical Rhetoric in British India: The 1897 Trial of Bal Gangadhar Tilak,’ South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies 39, no. 3 (2016): 546-559. DOI: 10.1080/00856401.2016.1196529

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Robert E. Upton, ‘Take out a thorn with a thorn’: B.G. Tilak’s legitimization of political violence,’ Global Intellectual History 2, no. 3 (2017): 329-349. DOI: 10.1080/23801883.2017.1370240

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Swati Parashar, ‘Colonial legacies, armed revolts and state violence: The Maoist movement in India,’ Third World Quarterly 40, no. 2 (2019): 337-354. DOI: 10.1080/01436597.2019.1576517

[19] Ibid.

[20] ‘Hany Babu’s arrest a “blatant silencing of dissent”: Jamia Teachers’ Solidarity Association’, July 29, 2020, The Caravan magazine. Accessed July 30, 2020. https://caravanmagazine.in/noticeboard/jamia-teachers-association-calls-hany-babu-arrest-silencing-of-dissent.

[21] Rajni Kothari, ‘Masses, Classes and the State,’, Economic and Political Weekly, 21, no. 5 (1986): 210-16. Accessed July 30, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/4375282.

[22] Swati Parashar, ‘Colonial legacies, armed revolts and state violence: The Maoist movement in India,’ Third World Quarterly 40, no. 2 (2019): 337-354. DOI: 10.1080/01436597.2019.1576517