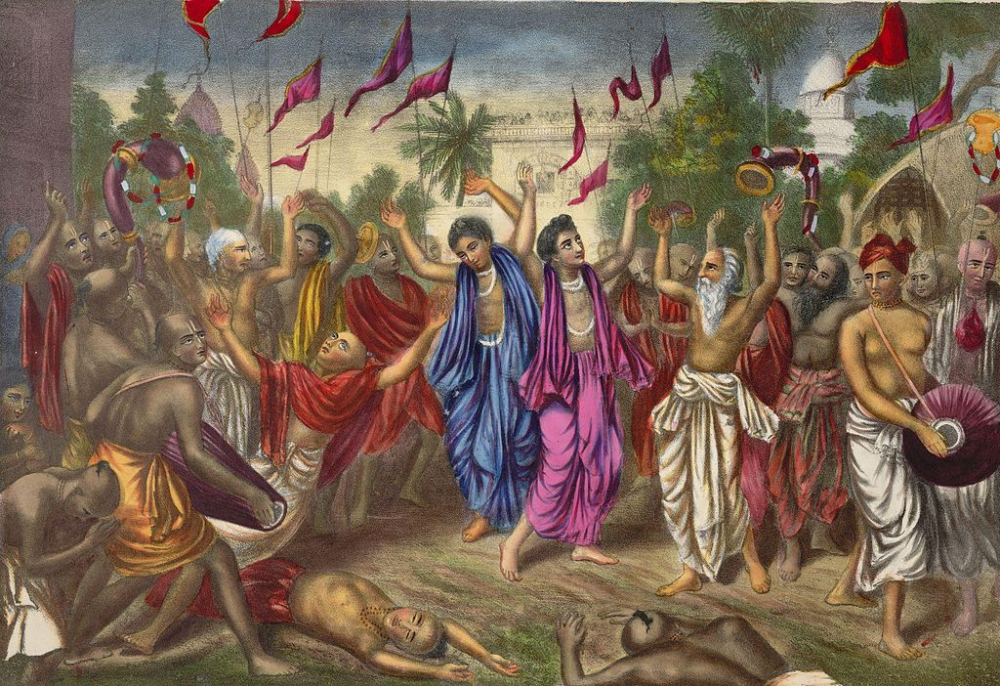

Chaitanya, the 15th-century saint, is known for his role in spreading Vaishnavism in Bengal. Often hailed as a socioreligious reformer, we look at modern research that has shown that while there is no denying Chaitanya’s extraordinary contribution to Vaishnavism, there are reasons to reassess his role as a reformer and the social implications of the movement that he led. (Photo Courtesy: Dinesh Chandra Sen [Public domain])

Sri Krishna Chaitanya (1486–1533), almost invariably shortened to ‘Chaitanya’, is a historical figure of great eminence, and understandably endowed with an ever-growing body of myths and legend. On the religious life of Bengal, the province where he was born, he made an impact comparable only to that made by Ramakrishna Paramahamsa (1836–86) much later. It is interesting too that Chaitanya and Ramakrishna represent the two major religious traditions known to Hindu Bengal—the Vaishnava and the Shakta, respectively. Both, incidentally, were Brahmins, a social and ritual rank that helped to consolidate their public status as teachers, scholars or spiritual practitioners. What concerns me here, however, is the way their historical presence has been defined and understood, especially with respect to the strength and resilience of a Hindu cultural and religious identity. Both these figures, for example, have been seen to symbolise an indigenous reaction to political subjugation and alienating way of life. In the case of Chaitanya, the ‘adversary’, whether real or imagined, was Indo-Muslim rule and with Ramakrishna, British colonialism.

In his time, Chaitanya was held as no less than a divinity, as God descended on earth to redeem humanity (In pic: Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu is shown performing 'kirtan', devotional chanting and dancing, in the streets of Nabadwip, Bengal; Courtesy: Calcutta Art Studio [Public domain])

Chaitanya as the divine?

In his time, Chaitanya was held as no less than a divinity, as God descended on earth to redeem humanity. He was acclaimed as an exemplary saint, a compassionate soul, an ecstatic, God-intoxicated figure who brought back social justice, piety and devoutness to a society hitherto afflicted by debauchery, social inequities and crass worldliness. This was the subject matter of several medieval hagiographies on Chaitanya that have now attained wide circulation, even among people who do not formally claim to be Vaishnavas. For many, these are classic and enduring contributions to Bengali literature. But while a hagiographic celebration of Chaitanya’s extraordinary life and work was only natural for his times, new arguments have also emerged ever since, foisting ideas or issues that are distinctly modern upon an individual who was quite clearly premodern.

Chaitanya as a socio-religious ‘reformer’?

One of the epithets consistently bestowed upon Chaitanya by modern Bengali authorship is that of a social as well as a religious ‘reformer’. In 1925, the American evangelist and scholar Melville T. Kennedy said that Chaitanya freely recruited people regardless of caste and based on their spiritual aspirations. However, modern historical research (such as by scholar B.B. Majumdar) shows that a majority of Chaitanya’s better-known followers were men from the three upper bracket castes of Brahmin, Baidya and Kayastha. And even though he ostensibly recruited women followers too, the number of active women participants was insignificant.

Also Read | Radha and Bhakti: In Conversation With H. S. Shivaprakash

There is an additional cause for questioning Chaitanya representation as a religious reformer too. Chaitanya did not write any learned philosophical treatises or build institutions of organised religious propaganda. While reform must be seen as an act of self-conscious mediation and a belief in the transformative power of human agency, Chaitanya, as far as one can tell, did not abide by this belief or strategy. He can be more aptly credited with the advice to substitute pedantry and ritual conformity by spontaneous god-remembrance: to be humble, compassionate, accommodating in one’s religious views and to give up ostentation in everyday life. Much of Chaitanya’s personal popularity and charisma flowed from the sheer simplicity and spontaneity of such teachings, such as when he told people to be ‘as tolerant as a tree, as humble as grass, to respect those whom society does not respect and to be always engrossed in god-remembrance’[i] from a collection of eight couplets called ‘Shikashtak’ that have been listed in the Chaitanya Charitamrita, written by Krishnadas Kaviraj Goswami in the 17th century.

Chaitanya through the lens of 19th century academics

In the 19th century, when Chaitanya rapidly emerged as an iconic figure for Hindu Bengalis anxious to draw useful lessons from their cultural past, some of his work was given contemporary political meaning. Thus, a well-known episode from Chaitanya’s life in which he and his followers defied the arbitrary orders of the local Kazi by prohibiting a Vaishnava procession was read as the first recorded instance of peaceful civil disobedience. Coming in the 1930s and 1940s, when indeed Gandhian ideas and movements had taken roots, this is not at all surprising. However, with respect to efforts at constructing Chaitanya into a political icon, we may also detect contrary trends. A small but significant section within the Bengali intelligentsia associated Chaitanya and his religion with emasculating sentimentalism, quite unsuitable for a people struggling to find a political voice. A good instance of this occurs in the novel Anandamath (1882) by Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay, where Chaitanya is accused of emasculating the Bengali people through his appeal to religious sentimentalism.

In the 19th century, when Chaitanya rapidly emerged as an iconic figure for Hindu Bengalis anxious to draw useful lessons from their cultural past, some of his work was given contemporary political meaning (Courtesy: Self [Public domain])

Also Read | Mystical Minstrels

Chaitanya and Gaudiya Vaishnavism in Bengal

There is some reason to critique the association commonly made between Chaitanya and Gaudiya Vaishnavism or Bengal Vaishnavism. For one, the tradition doctrinally labelled as Gaudiya Vaishnavism is almost wholly a post-Chaitanya phenomenon, a creation of the so-called Goswamis, pious scholiasts located in Vrindavan, in the 16th–17th centuries. The geocultural roots of this theology when joined to the fact that as many as four of the six Vrindavan Goswamis were of southern origin, disqualifies claims of a purely Bengali provenance. It was a pan-Indian Vaishnava following that they were targeting, not the local or provincial. The literature that they produced was written in cosmopolitan Sanskrit, not the vernacular Bengali. We must also be careful to acknowledge that the roots of Radha–Krishna worship—on which Chaitanya and his followers based their theology—are far older. Modern research also reveals the presence of rival Vaishnava traditions within Bengal itself. Hence, while there is a good reason to call Gaudiya Vaishnavism the dominant tradition within Bengali Vaishnavism, it is definitely not the quintessential. That apart, attributing Gaudiya Vaishnavism solely to the religious teachings of Chaitanya remains historically questionable.

This article was also published in The Telegraph

Notes

[i] The verse, ‘Trinadapi sunichena, toruriba sahushnena, mananiya amanena, kirtanaya sada Hari’, has been translated from Sanskrit by the author.