M.Natesh (b.1960) is a polymath of an artist with a prodigious output of paintings and drawings. Additionally, he works as a theatre director, lighting designer for dance and theatre, installation artist, and an actor trainer. Discovered to be a child prodigy by his parents (his father is the Tamil writer and playwright N. Muthuswamy), he was encouraged to pursue drawings even as a child. The web of artistic engagements in different fields and his father's literary milieu, in which he grew up, greatly influence his paintings. Of all the fields, Natesh’s forte lies in his drawings which are high in artistic merit, prodigious in number and matchless in revealing the workings of his artistic mind. As years passed by, Natesh’s lines grew stronger, more confident and more in tune with the speed of his thoughts and imaginations. The latest exhibition of his works at Dakshinachitra in August 2015 appropriately titled, ‘Line is the spine of self: any self’, revealed the centrality of drawings to his art. Natesh’s drawings are spontaneous, and they give the impression of being one single line. They capture the vertebrae of humans, birds and animals both literally and metaphorically. In the archive of Natesh’s thousands of drawings, one discovers his visual motifs that constitute the vocabulary of his paintings, installations and murals. Flying human organs, a hand with a pointing finger and an uplifted thumb, a playful Ganesha, a mocking bird, sandboxed activities, theatrically juxtaposed human comicalities, and images of death, sex and extinction populate Natesh’s universe of meaning and representation. As an artist of ideas, Natesh credits his teacher-artists at the Madras College of Arts and Crafts, Chandru and R.B. Baskaran, for liberating his lines to convey precise meanings. However, Natesh does not reveal his lines in his paintings but hides them behind the intensity of his colours.

That Natesh plays with the tonality of colours is evident in ‘Womb’ (Fig. 1). Pink and red alternate and provide the contrast for the black, while the white acts as the light to illuminate portions of the painting. We do see a foetus clearly inside a pregnant belly, but what strikes us is the chaotic order of the mini-universe Natesh presents. Framed inside the thick black frames, we vaguely recognise the suggested figure of the woman and the black foetus dominates the painting. Natesh's use of colours is very much in tune with that of painters connected with the Western art movement Fauvism. Henri Matisse, the leading exponent of Fauvist movement, wrote in his famous ‘Notes of a Painter’: ‘the chief function of colour should be to serve expression as well as possible. I put down my tones without a preconceived plan. If at first, and perhaps without my having been conscious of it, one tone has particularly seduced or caught me’ (‘Fauvism Movement, Artists and Major Works’ 2016). Natesh uses pink and red as if here were a Fauvist quite spontaneously and the figure seems to emerge from his brush strokes.

Fig. 1: 'Womb' (1999); acrylic on unprimed canvas; 3 feet x 4 feet

Fig. 2: ‘Cartoon Network’ (2000); acrylic on unprimed canvas; 3 feet x 3.5 feet

That Natesh uses his brush more as a draughtsman's pen, or a pencil, is further evidenced by his painting ‘Cartoon Network’ (Fig. 2). Cartoons are a major source of inspiration too, for Natesh, and he relishes the rebellious quality of funny animations. In ‘Cartoon Network’ a human head that watches a cartoon animation is permeated by those figures, and it becomes an extension of the cartoon itself. Natesh highlights the pink and red with strokes of Bondi blue. We see a strange face emerging with chicken feet from this comical merger. Natesh cites comic books as the reference works of his childhood and adult imagination. We see that the hidden cartoons and the figures exhibiting comical body language and gestures become the primary constituents of Natesh's paintings and drawings. Speaking about his early childhood fascination with comics, Natesh says, ‘My dad introduced me to Phantom comics, and horses galloped into me. But the first conscious moment, which demanded a drawing from me, happened when I saw a patch of peeled-off whitewash, that resembled a horse, on our old wall. More than the horse from my world of Phantom comics, it was that anomaly which triggered it. I never used to see it that way, for a long, long time. But these days, when I effect the same accidents on my work and plug the hole, the patch, the anomaly, with the drawing, which it resembles or some other drawing which I force on, I sharply recollect the moment, that particular moment. It is this spark which imprisons life in my work. Sometimes fully, at other times, by rote’. ‘Cartoon Network’ picturises Natesh's existential outlook which he weaves into his other paintings as well.

Fig. 3: ‘Well Fed Chick’ (2002); acrylic on unprimed canvas; 3 feet x 3.5 feet

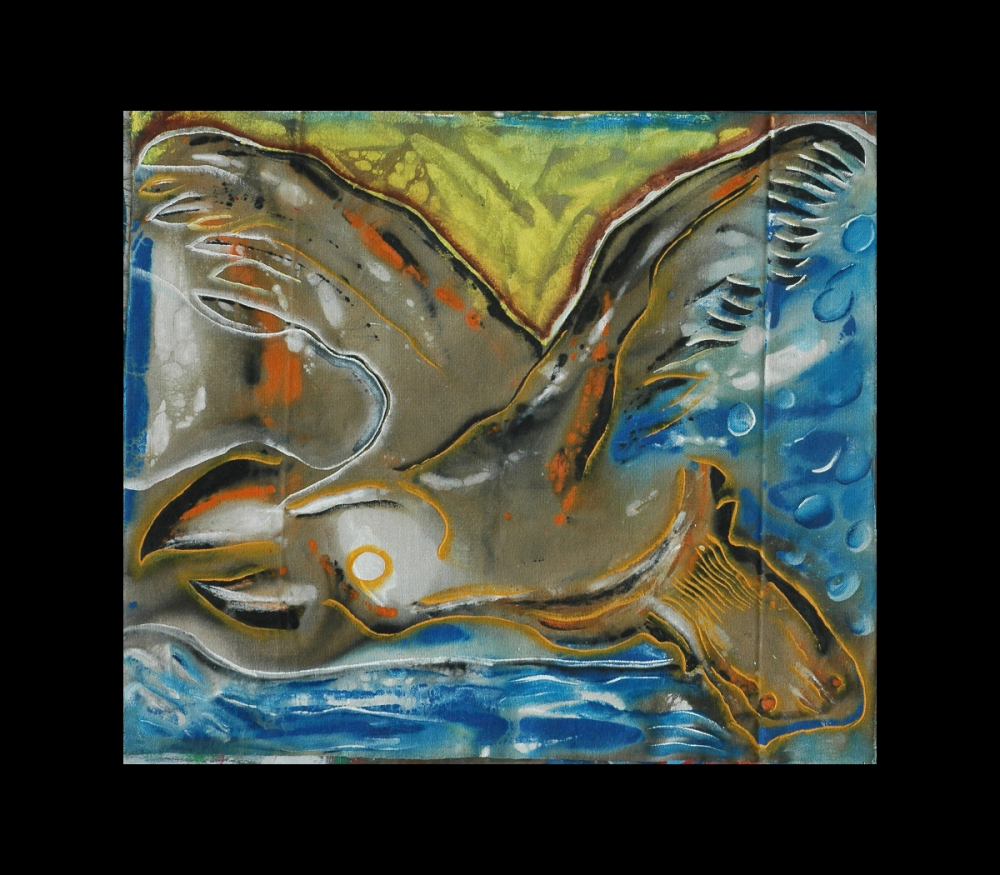

‘Well Fed Chick’ (Fig. 3) reveals Natesh's fauvism to be not of a drawing room variety, but depicting the reality of inner consciousness. While the play of light and transparencies is the most outstanding feature of this painting, it is the unique colour combination of stained brown and sea blue that makes the painting striking. Natesh's prominent visual motif, the little bird assumes an expression of horror with the vampire teeth on the beak.

Fig. 4: ‘Baby Bird’ (2003); acrylic on unprimed canvas; 3 feet x 2 feet

Natesh raises the little mockingbird in his paintings both as a persona and as a commentator. Sometimes, the bird symbolises the primordial fear which Natesh calls the missing link in human evolution. In his apocalyptic cosmology, the fear that is sown in the womb is both the cause of the evolution of the species and the force towards its extinction. The well-fed chick of the womb becomes the bird of terror in flight in ‘Baby Bird’ (Fig. 4). ‘Baby Bird’ is surreal, and the painting manipulates the source of light which is seeping through the transparent wings of the bird. It is almost as if the sun is behind the flying bird. Natesh writes, ‘Can you erase light? Sun’s light? Tall claims are made by those who are ready to climb it all the way! Tallest of the tallest. Till rhetorics commit suicide, or till the object erases its shadow, for it can do nothing with the sun, not even in a dream’. Natesh acknowledges the influence of ‘L'Ange du Foyer’ by Max Ernst (1891-1976) in his painting ‘Baby Bird’. As an early Dadaist, Ernst developed a fascination with birds that was prevalent in his work. His alter ego in paintings, which he called ‘Loplop’, was a bird. He suggested that this alter-ego was an extension of himself, stemming from an early confusion of birds and humans. Natesh exhibits similar tendencies to those of Ernst, but such influences do not persist and develop into a lasting trait in Natesh's paintings. Natesh is a prolific painter who erupts into a series of expressions and lulls into a hibernation only to explode again, but in an altogether different rhythm of colours and speak compositions. Soon it becomes clear that Natesh's painting possesses an inner light, the light that an inner vision knows and expresses in the world of bright colours, in the world of sunlight. His visions are sometimes terrible and sometimes comical, but he knows the source of light and how to manipulate it. He has a passion for the colours he combines, and they represent his conflicts.

The wildness and its Fauvism are his interiors. ‘Blind Bird of Consciousness’ (Fig. 5) further illustrates Natesh's pictorial conception of his mental world. The bird flies blind to the light and sky surrounding it, but its eeriness is unmistakable. The strange plasticity and fluorescence of the bird accentuate its blindness, its flight to nowhere, and its disastrous being in time. The blind bird is frightening because it has the freedom to be in its own self, here and now, but it cannot see and know its being in the world.

Fig. 5: ‘Blind Bird of Consciousness 1’ (2005); acrylic on unprimed canvas; 3 feet x 2 feet

We see a reversal of blindness in ‘Dawn’ (Fig. 6) where human eyes are littered over the sky in the right-hand corner of the canvas. The eyes are not particularly looking at the bending human figure created by the colour beams. Only one eye on the top of the canvas is staring at the viewer while the other eyes are either squinting or looking elsewhere. The dawn appears to abandon the slouching human figure. Writing about the history of Fauvism, Natalia Brodskaïa says that the Fauves were anarchists striving after the free expression of their individuality, taking a stand against tradition and generally accepted standards of beauty (Brodskaïa 2011). Natesh's turmoil fits the description of Fauves, admitting his stance is more of an existential nature. Split into the beams of colour, the slumped human figure appears to be ignored by the indifferent eyes of the sky as if it is a scene captured from an unfolding Greek tragedy. About anarchy and madness Natesh writes in his noteboook. ‘So madness, not the pathological one, but a well-constructed, cultivated madness. Personally, I would come back to it again and again. Such a thing is a larger manifestation of one’s obsessions, a string of obsessions that blend well and lead you into illogical, impractical areas of thought, which, in my case, get expressed as paintings and installations. Obsession is destructive, if not the other, it ruins the self when one is also obsessed with wonderful utopian dreams of divine bliss, equality, etc. 'Anarchic' is a proper adjective but madness touches everybody. I need to call it conscious madness. Anarchy is one among those rebellious intentions that did everything to become a way of life. But no intention can do a thing in terms of rebellion since we have the solidity of one regulatory structure, language. Any intelligence that has an access to language even with the worst method of training, is regulated’.

Fig. 6: ‘Dawn’ (2005); acrylic on unprimed canvas; 3 feet x 3.5 feet

Fig. 7: ‘Flight 2’ (2005); acrylic on unprimed canvas; 3 feet x 2 feet

The heroism, then, is of course about the flight of the lonely bird that splices the sky as we see in ‘Flight 2’ (Fig. 7). The blue background merges the sea and the sky and the bird seems to emerge from a pursuing storm. The bird has lost its wrathful looks of the ‘Baby Bird’ (Fig. 4), but its eye has turned white and blank in its intensity. The bird in the painting does not have a destination, and it is frozen in its flight; its heroism is not even tragic, as it is driven only by the desire to escape. Natesh would not like the verbalisation of the flight of the birds in his paintings since he thinks language is a regulatory mechanism against which his constructed madness and anarchy are cultivated. Natesh would argue for pictorial abstractions which convey extra-linguistic meanings and emotions. Again, Natesh would personalise his abstractions and argue:

Abstraction is like love, you cannot define it, it is as mad. One is absolute; two is political. That is a little too abstract, but abstraction is a reservoir of truth. Abstraction has been temporarily relegated to the background, these days when consumerism is ruling the planet. It can either be a confounded, perplexing situation or a moment of great clarity that calls for abstraction. Abstraction will have its validity reposed when we look at any hypothetical or practical situation in the sciences, where each situation is woven by numerous activators, lending it a complexity comparable to abstraction. Abstraction is a meditative state of mind ruled by the turbulence of spirit, which isn’t perturbed by choice. The element of choice and the hierarchy of choice hoists and upholds human agony, which refuses to comprehend the degeneration of the organic qualities of life which is essential for its regeneration and its temporal continuum. However, doesn’t it look like retirement benefits heaped upon the well-behaved bureaucrat? When choice rules the planet, narration, conception and criticism race with each other in the political gamble that life has become.

Natesh's observations about nature, especially about birds and animal behaviour, turned him towards ecological feminism and he became convinced that male world-view is leading the humanity towards its extinction cycle. Simultaneously, he began to admire Wassily Kandinsky's works. Rather than cloaking artifice, Kandinsky's works drew attention to the conventions, procedures and techniques supposedly inherent in a given form of art. In its emergence, Kandinsky's abstraction owed much to Fauvism and expression theory, and he saw his art as a harbinger of the apocalypse (Edwards et al. 2012: 533). Natesh's attractions towards Kandinsky are evident, but it could have occurred through Indian artists of the early modernist era. Writing about Kandinsky's influence on the early Indian modernists, Partha Mitter writes that an ambitious exhibition of the works of Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky and other Bauhaus artists held in Calcutta in 1922 marks the beginning of the avant-garde in India (Mitter 2007:10).

Natesh's ‘Inside the Apple’ (Fig. 8) is an expression of Kandinskian pure form in the sense that it does not refer to a real object, and it shines genuinely on the relations between colours and shapes. The Fauvist red is there with a passion and an unreal apple in a box houses a fish. The box is connected to another shapeless apple which also has a fish-like figure inside. The painting resists conceptualization and demands the viewer to appreciate its abstract beauty. Natesh records in his notebooks:

Abstraction is a problem. And it will continue to be a problem. To overcome is a cognitive, instinctive, survival reflex. With the growing scale and scope of cognition, the need to overcome ignorance would continue to be a process for intelligence. In the area of scientific enquiry, classification of structures and the problems posed by the basic units that are the bricks of the universe that acquire validation through proof. And questions remain hypotheses, acquiring validation with each proof, or the semblance of a proof. Abstraction in expression would continue to exist with the same need to overcome. Refusing to portray is the first step towards non-voyeuristic individuality, given to deeper, cognitive-referential-engagement.

Fig. 8: ‘Inside the apple’ (2005); acrylic on unprimed canvas; 3.5 feet x 3 feet

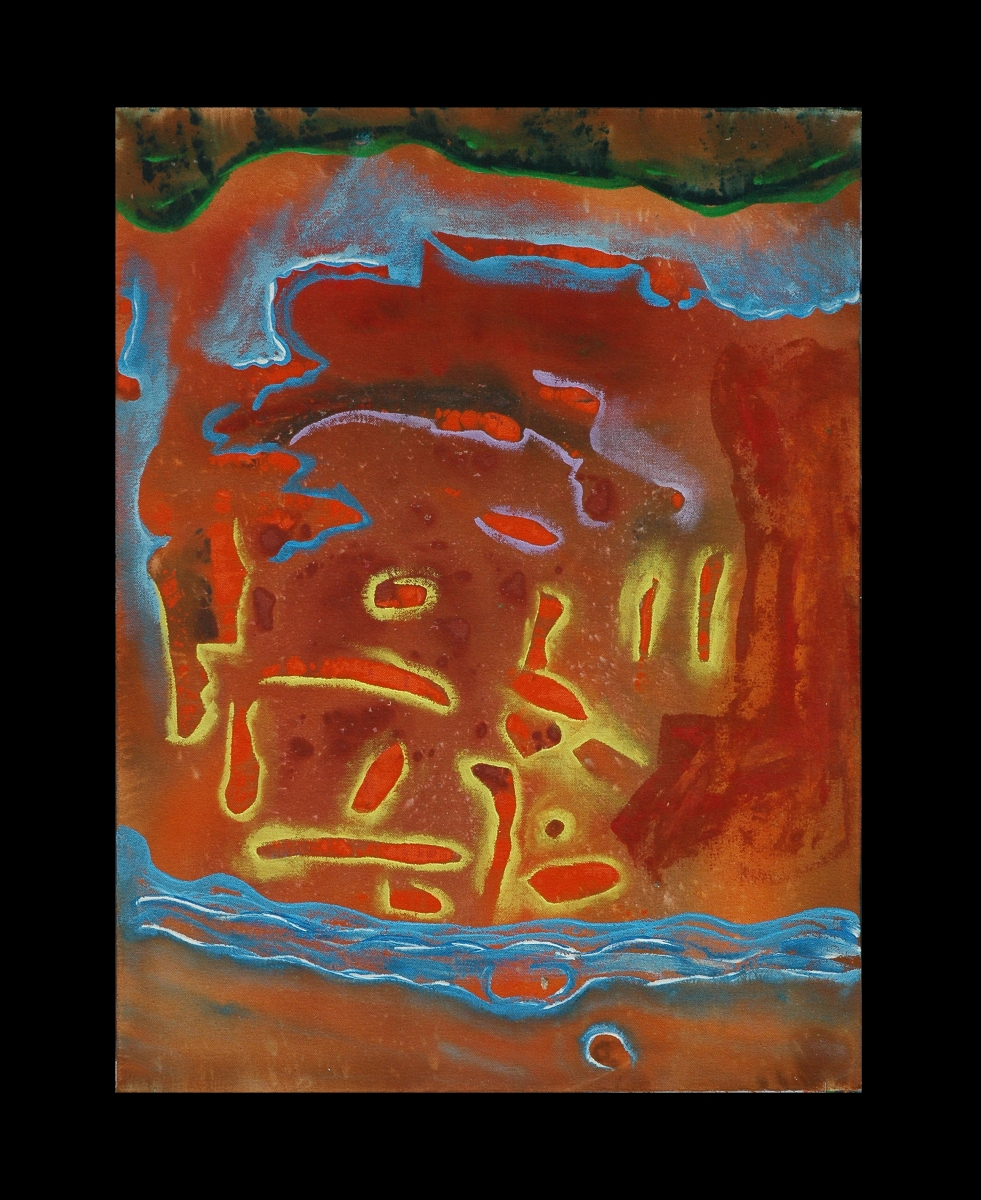

‘Desert River’ (Fig. 9) is again Kandinskian in its form and execution. The painting depicts the strong flow of a river surrounded by the fiery patches of red. It resembles an aerial view of a patch of land in a desert with borders of green on top and blue at the bottom. It is the survival of the river that captures one's attention despite the overwhelming presence of the red. Stella Kramrisch once wrote that the transformation of the forms of nature in the works of an artist is common to ancient and modern India and it is not naturalism, but it is infusing a subject of painting with an inner experience. Natesh would not attribute metaphorical meanings to such transformations of natural forms in his paintings, and he considers metaphor is the end of the experience. He would further declare that metaphor as a strategy would kill wonderment of first encounters with the forms of nature. When you defrock the ‘Desert River’ from its possible worldly references and metaphorical meanings, the painting emerges as a visual play of colours, forms, and shades, enlivening cognition.

Fig. 9: ‘Desert River’ (2006); acrylic on unprimed canvas; 3.5 feet x 2 feet

Fig. 10: ‘Kandinsky’ (2007); acrylic on canvas; 5 feet x 2.5 feet

‘Kandinsky’ (Fig. 10) is both Natesh's tribute to Kandinsky and an indication of his internalisation of the Russian artist's spirit. Divided into two panels, a squirrel in the right panel of ‘Kandinsky’ watches a roaring tiger in the left. Defying representation, the panels constitute a narrative moment one artist looking at the genius of a master. It brings into focus the disinterested contemplation on Kandinsky's lasting influence and spiritual journey. Although sceptical about narration, Natesh favours an abstract narration which resists formalism of any school. Natesh would argue for keeping a point of reference to understand natural evolution. He observes in his notebooks, ‘There are no roots. If you go in search of roots, you will see bloodshed, conspiracies and war. In the area of nature, ice ages, earthquakes, colliding meteors, disappearing landscapes into the seas and deserts spreading their heat on forests, converting them into oases and the extinction and metamorphosis of life. Kandinsky offers a way of perceiving the workings of nature.’ In ‘Kandinsky’, a squirrel watching a roaring and dying (?) tiger is akin to Natesh observing Kandinsky.

Fig. 11: ‘Pet’ (2007); acrylic on canvas; 3.5 feet x 3 feet

Fig. 12: ‘See Saw Gajini 1’ (2008); acrylic on canvas; 5 feet x 4 feet

Fig. 13: ‘Time is up’ (2008); acrylic on canvas; 4 feet x 3 feet

With the practice of public installation art, Natesh's paintings changed significantly. Though Natesh continues to oppose conceptual art in paintings in installations, he adopts conceptual modes inculcating aspects of storytelling from his drawings and interactions with popular culture expressions. Natesh uses tonality, opacity, and transparency as chief techniques in his paintings and introduces collage to create dramatic effects. ‘Pet’ (Fig. 11) and ‘See Saw Gajini’ (Fig. 12) best demonstrate the change in Natesh's art. Explaining the process of his installation art Natesh says:

Each medium has its well set physical parameters: drawing is point specific, small and less physical, painting is colour specific and uni-planar, installation is a tiring blood-sucker, since it is political and five dimensional (3d+metaphysics+time). Though time is an exciting component of installations, it eats your time and ‘desertifies’ your pocket. Theatre needs alcohol, people, space, time, language and other imaginable personal inputs. When the idea for an installation happens in my head, I write, draw and paint. It is a four-in-one activity. Theatre came to me as a legacy. The performance day, and moving towards it, is theatre’s neurosis. Painting, drawing and writing have completely different neuroses. Neurosis is a bad word; it is a word used by the voyeur to describe the makers’ predicament. Let me call it a magnificent obsession. So, an osmosis of obsessions. The general phrase to describe it would be obsessions’ osmosis.

But the first infliction happens from the Media. I read the newspaper early in the morning before my morning walk. Mornings are fresh. To tell you the truth, my creating time gets over by 10 or 11 in the morning. Some days when the intensity is heavy and clouded, it stretches up to 2 in the afternoon. Not a minute beyond. This personal information is important for the process. This is when, what I read in the papers and the news value that inflicts an idea, metamorphoses into a drawing or an installation. Never into a painting does it become, since the process of painting is a different holistic catharsis in colour. A totally different trip.

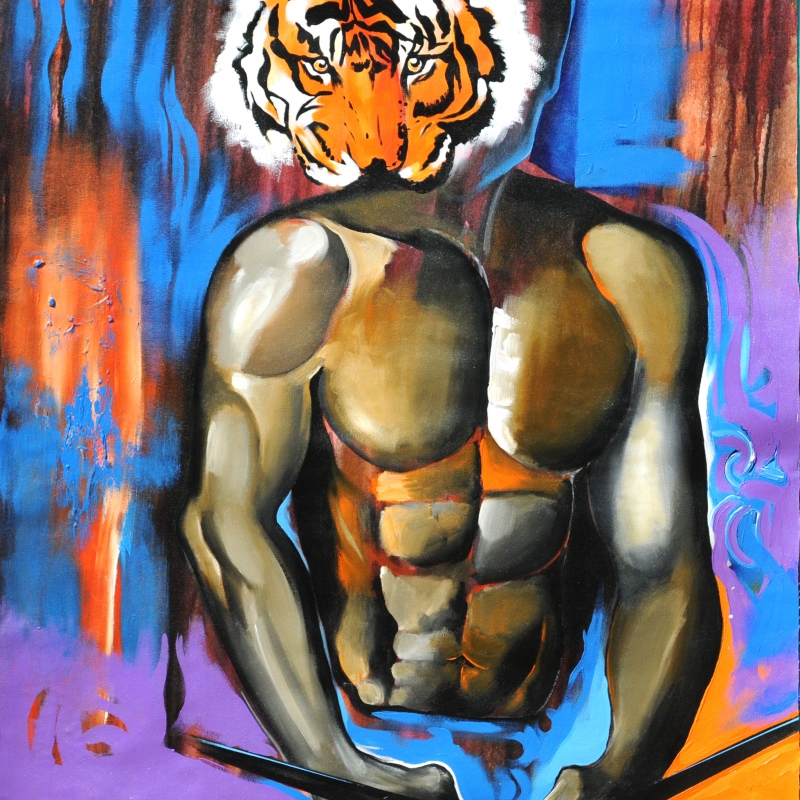

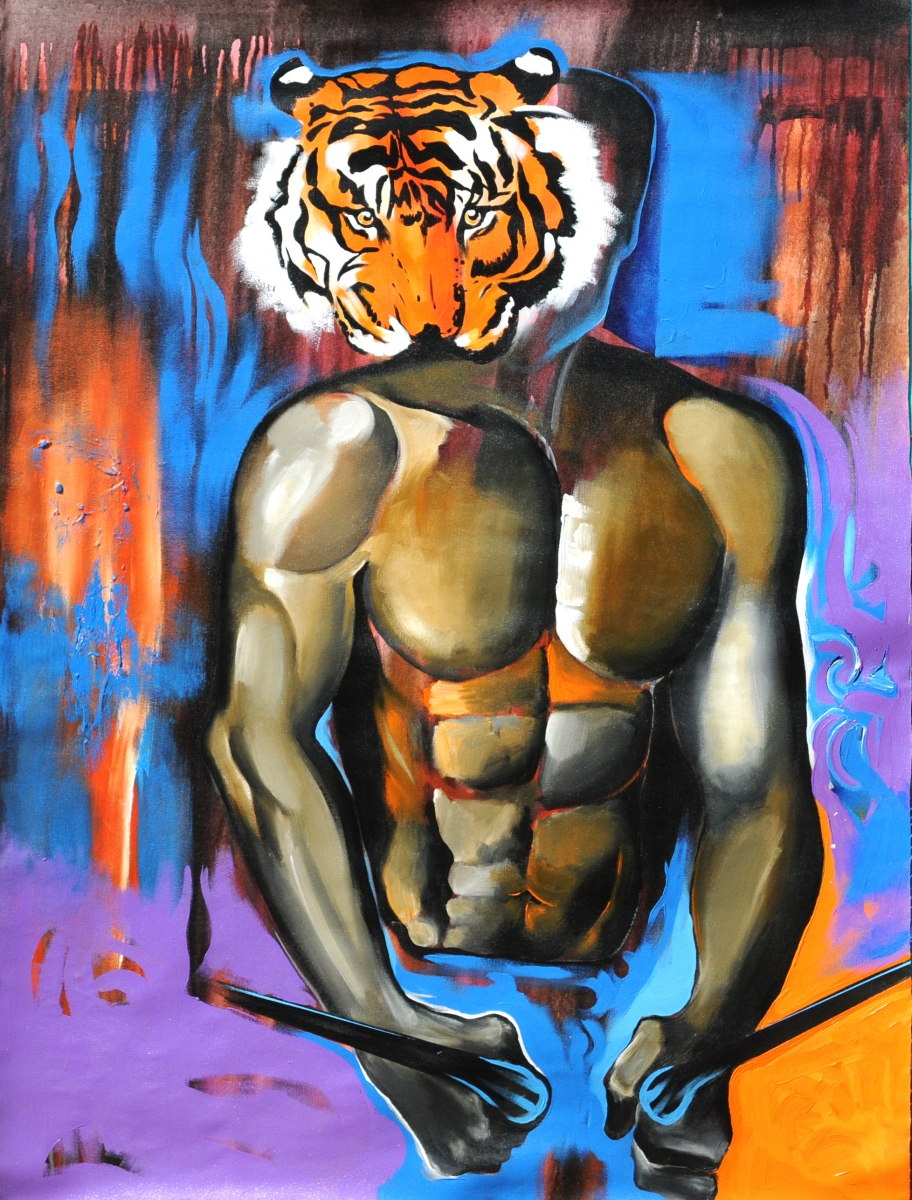

Natesh's paintings from 2007 onwards announce his angst loudly, and they purposefully look unfinished and crude. His angst has its origin in the ecological feminism he has adopted and the disgust he harbours for the expressions of popular culture. He records in his notebooks, ‘So soap-ops are not a mistake, we deserve them. Let me repeat...Yes, the violence, enmity, hatred, disgraceful behaviour in middle-class households are portrayed truthfully. Soap-ops are God-sent bounties for commercials. Everyone, I suppose would shut off the volume when they arrive, like mosquitoes in the evenings when we shut the windows to avoid large numbers. This alone is enough, to swear, for the intelligence of our populace since they are not letting them plant demands at will’. In a series paintings named after a commercial Hindi film ‘Gajini’, Natesh ridicules the muscular male body revered in the film. In ‘Gajini 1’ (Fig. 15) the face of a six-pack muscles of a male torso has the face of a tiger, and it looks artificial like a film poster and offends the viewer with its garish colours.

Fig. 14: ‘Gajini 1’ (2009); acrylic on canvas; 4 feet x 3 feet

Fig. 15: ‘Global Warming’ (2011); acrylic on canvas; 5 feet x 4 feet

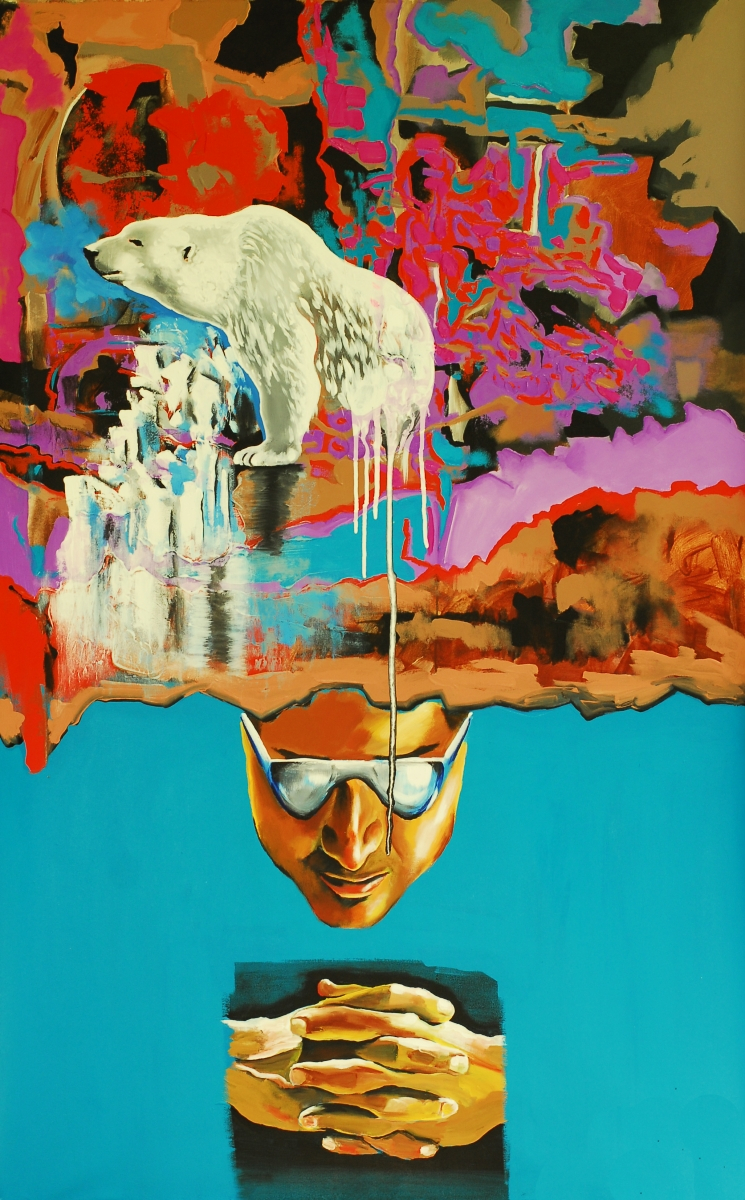

Fig. 16: ‘Polar Bear’ (2011); acrylic on canvas; 5 feet x 3 feet

Natesh finds new uses for his techniques of tonality and transparency in his paintings on environmental concerns and global warming. In ‘Time is up’ (Fig. 13), ‘Global Warming’ (Fig. 15) and ‘Polar Bear’ (Fig. 16) we see we see a photo montage of images drawn from nature photography, popular films, and boxed gestures placed inside a splash of colours.

Natesh uses the gesture of the clasped hands as a symbol of man's will and determination to destroy the planet. While these paintings do not demand any interpretation and their communication is immediate, the urgency in these paintings is distinct. Natesh's apocalyptic vision borders on a spiritual gravity. In a diary entry titled, ‘Shwish, Whuff, Bang, Ding’, Natesh writes, ‘I need to cleanse in public to safeguard myself. God-boy trip is fun, but minimum trust and faith are essential to be thoroughly cheated by ART. Some might digress, to register their dissidence on clubbing them together, trust and faith. Both come from similar corners and deal with cheating in different ways. When I say, ‘thoroughly cheated by art’ the truth of this statement is spirituality’.

References

'Fauvism Movement, Artists and Major Works.' 2016. The Art Story. Online at http://www.theartstory.org/movement-fauvism.htm (viewed on August 19, 2016).

Brodskaïa︡, N.V. 2011. The Fauves. New York: Parkstone Press International.

Mitter, Partha. 2007. The Triumph of Modernism India’s Artists and the Vant-Garde 1922-1947. London: Reaktion Books Ltd.

Edwards, Steve, and Paul Wood, eds. 2012. Art & Visual Culture, 1850-2010: Modernity to Globalisation. London; Milton Keynes: Tate Publishing in association with the Open University.

[1] Natesh made his private notebooks titled 'A bottle not so new' available to me and all my quotes in this essay are from those notebooks.