An introduction to the caves and its carvings

Elephanta island, also known as Gharapuri (which denotes a hill settlement, a name used in the local Marathi language), is located in the Mumbai harbour. It is a picturesque island, surrounded by mango, tamarind, karanj (Pongamia pinnata) and palm trees (Fig.1). Its presence on the world map is due to a unique group of caves, which was identified by UNESCO as a World Heritage site in as early as 1981. Presently it is under the protection of the Archaeological Survey of India which is responsible for its continuous maintenance and upkeep.

Fig.1. Elephanta Island

(Photo courtesy: Khalid Ahmad)

The appellation Elephanta was given by the Portuguese on account of their discovery of a huge sculpture of an elephant near the old landing place (Fig.2). The sculpture, which was in a poor state of preservation, was later repaired and installed at the Jijamata Udyan Zoo in Mumbai, known earlier as Rani ka Bagh or the Queen’s Garden.

Fig.2. Elephanta elephant sculpture

(Photo courtesy: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Elephanta_Caves#/media/File:Elephanta_Elephant.jpg)

Caves on an island are a rarity as most of the caves of western India are located on the Sahyadri range. There has been a larger number of cave temples excavated in western India than the rest of the country because of the nature of the rock, which was conducive for carving. The trap rock or basalt rock found here is one of the most suitable rock types for the kind of fine and minute carvings that are witnessed at Elephanta.

The caves are in two groups: the first one is a group of caves dedicated to Lord Shiva and represents some of the most exquisite examples of sculptural detailing in India, while the second one, which is slightly smaller than the first group, consists of two Buddhist Caves. The caves range between 5th and 8th centuries A.D. (the debates around this dating will be discussed later in the article). There is evidence that the caves were once painted but most of the paintings have peeled off due to the damaging effects of time, climatic changes and human vandalism.

Geography

Elephanta Island is about 7 miles (11 km) east of Apollo Bunder (Bunder means a port or pier) on the Mumbai Harbour and 6 miles (9.7 km) south of Pir Pal in Trombay. The island covers an area of about 4 square miles (16 km) at low tide. It was commonly known as Gharapuri because a village by that name is located on its the south side. The Elephanta Caves can be reached by ferries that ply from the Gateway of India, Mumbai. The ferry ride takes about an hour and operates daily except during the monsoon from June to August.

The small island features two hillocks separated by a narrow valley. These hills rise to a height of about 500 feet (150 m). A deep ravine cuts through the heart of the island from north to south. On the west the hill rises gently from the sea and stretches east across the ravine and rises gradually to the extreme east to a height of 568 feet (173 m). This hill is known as Stupa Hill. The foreshore is made up of sand and mud with mangrove bushes on the fringe. Landing quays sit near three small hamlets known as Set Bunder in the north, Mora Bundar on the northeast and Raj Bunder in the south where Gharapur is located. It is a protected island with a buffer zone according to the notification issued in 1985 which also includes a prohibited area that stretches 1 km (6.62 m) from the shoreline.

Protection of the Island

The main caretaker of the Elephanta Caves is the Archeological Survey of India (ASI) that is responsible for the continuous maintenance, support and preservation of the monument. The ASI is also supported by other departments that include the Forest Department, Tourism Department, Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority, Urban Development Department, Town Planning Department and the Gram Panchayat of the Government of Maharashtra all acting under various legislations of the respective Departments such as the Ancient Monuments and Archeological sites and Remains Act (1958) and Rules (1959), Ancient Monuments and Archeological sites and Remains (Amendment and Validation) Act 2010, Indian Forest Act (1927), Forest Conservation Act (1980), Municipal Councils, Nagar Panchayat and Industrial Township Act, Maharashtra (1965) and the Regional and Town Planning Act, Maharashtra (1961).

The caves are located in the Arabian Sea and hence are highly impacted by saline activity as well as natural climatic changes. High water seepage in the caves due to heavy rainfall during the monsoon season has also been causing intense damage. Rock erosion is also corroding the sculptures, creating a need for strong technical safeguarding. Another threat comes in the form of industrial development in the area which is hazardous to the longevity of the caves. Some of the pillars inside the caves are in bad shape and need urgent restoration. Cracks have developed in certain areas which require immediate repair. Hence the caves call for a planned management of conservation and preservation along scientific lines.

History of the Caves

Unlike all other caves of western India, these cave temples have no authentic history; much of what has been written on them has been based on conjectures and assumptions by various scholars and historians. There has been a controversy around the dating of Elephanta but no one as yet has been able to arrive at any definite conclusions.

Unfortunately, a large stone inscription found on the site by the Portuguese has been irretrievably lost. Diogo de couto made the following entry in the Annals, “When the Portuguese took Bacain and its dependences they went to this pagoda and removed a famous stone over the entrance that had an inscription of large and well written characters, which was sent to the king, after the Governor of India had in vain endeavored to find out any Hindu or Moor in the East who could decipher them. And the king D. Laao-III also used all his endeavors to the same purpose, but without any effect, and thus the stone remained there and now there is no trace of it”. Considering the fact that the Brahmi script was first deciphered by James Prinsep in 1837, an official of the Calcutta Mint and Secretary of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, it is not surprising that the Portuguese king could not find anyone who could read the inscription.

Since no inscription now exists, the dating of the Elephanta caves is purely conjectural as mentioned earlier. Many opinions have been expressed on their chronology. Besides the early scholars like James Burgess, James Fergusson, Stella Kramrisch and Hirananda Sastri who have given dates ranging from the 5th century A. D. to 8th century A. D. (they have however not justified these dates), other scholars like Dr. V.V. Mirashi, Dr. Walter Spink and Dr. Y.R. Gupte have very lucidly discussed the dating and have tried to logically prove their contention. The caves have been attributed by Y.R. Gupte to the Maurya dynasty. Dr. Mirashi accepts Gupte’s dating, but attributes their excavation to the Kalachuris. Benjamin Rowland supports James Burgess’s dating of the latter part of the 8th or the beginning of 9th cent. A.D. Fergusson placed them in 750 A.D. Stella Kramrisch considers them of Rashtrakuta period and places them in the 8th cent A.D. However, none of them discuss the chronology.

Dr. Mirashi however, who dates the caves to the early half of the 7th century, gives arguments which are partly historical and partly those of religious affiliation. He disputes Gupte’s contention that the cave was excavated by the Mauryas of the Konkan on the grounds that since they were merely feudatories of the Kalachuris, they could not have commanded the resources required for the excavation of such a rock temple. He further contends that though the Chalukyas of Badami conquered Gharapuri in the second half of the 7th century A.D., the caves however cannot be attributed to them as they were devotees of Vishnu and therefore could not have carved Shiva temples.

According to Walter Spink, in his The Great Cave at Elephanta: A Study of Sources, the ownership of the caves has been attributed to the Kalachuri dynasty. Dr. Shobhana Gokhale’s paper concluded that copper coins issued by King Krishnaraja, the great Kalachuri ruler, have been found in fair numbers in western India in the mid-6th century. Thousands of coins have turned up on the island of Gharapur. With the logical support of coins discovered at Elephanta, Spink contends that Elephanta is a mid-6th century Kalachuri monument sponsored by the great king Krishnaraja.

Dr. Ramesh Gupte has categorically refuted both the arguments of Dr. Mirashi as well as Dr. Spink and asserted strongly the influence of Chalukyas due to the presence of maniyajnopavita (pearled sacred thread) as the mani (pearl) and pushpa (flower) yajnopavita adorn all the sculptures of Chalukyas such as those at the Aihole, Badami and Pattadakal temples. Other indications of Chalukya influence are the armlets (keyuras) with kirti-mukha (Face of Glory), and also the presence of Saptamatrikas, Karttikeya and Shiva, as it is well known that the Chalukyas were their followers. Furthermore, the Chalukyas in the 6th century A.D. had defeated the Kalachuris. Later dynasties like the Rashtrakutas and the Gujarat Sultanate surrendered Gharapuri to the Portuguese. The Portuguese later left in 1661 as per the marriage treaty of Charles II of England with Catherine of Braganza, daughter of King John IV of Portugal. This marriage shifted the possession of the island to the British Empire.

However, during the rule of the Portuguese the caves were grossly vandalized by them and damaged to a huge extent. They removed the valuable inscription mentioned earlier from its place and used the sculptural reliefs as target practice, thus marring a great number of sculptures.

Cave Details

As mentioned earlier, the island has two group of caves in the rock architecture style. The first group consists of five Hindu caves while the second group of two Buddhist caves.

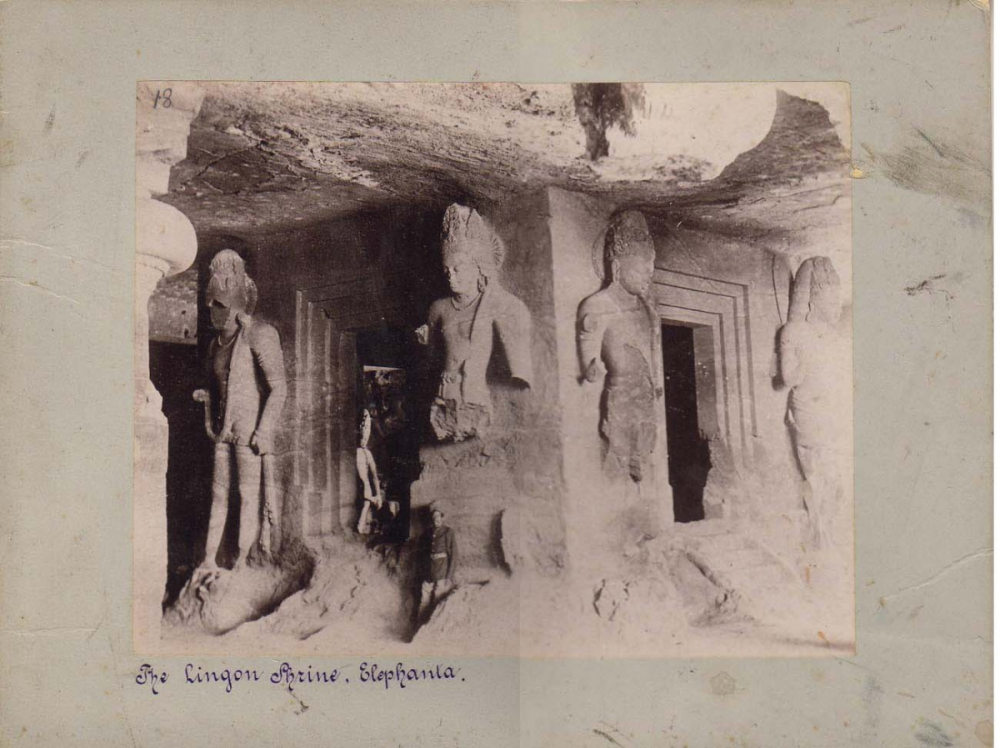

The Main Cave or Cave-I also called the Shiva Cave-I or the Great Cave is of huge dimensions: it is 38.40 meters deep and 37.80 meters wide. Rows of columns divide the hall into corridors (Fig.3). Twenty-four columns support the ceiling of the hall. At the back end of the temple is the famous Maheshamurti, while the shrine with the linga, the main object of worship in a Saiva temple, is on the right side.

Fig.3. Main Cave-1

(Photo courtesy: American Institute of Indian Studies, Gurgaon)

The ground plan of the temple clearly indicates that the northern entrance was the principal one. Though Maheshamurti is considered by most to be the principal object of worship, it is the linga shrine which stands facing the Nandi that is the main object of worship. The roof of the column has concealed beams supported by stone columns joined together by capitals. The cave entrance is aligned with the north-south axis, unusual for a Shiva shrine which generally has an east-west axis.

The northern entrance, which has 1000 steep steps, is flanked by two panels of Shiva dated to the Gupta period. The left panel depicts Yogishvaraj (Shiva as the Lord of Yoga) and the right shows Nataraja (Shiva as the Lord of Dance). The central shrine is a free standing square cell with four entrances, located in the right section of the main hall (Fig.4). There are smaller shrines located in the east and west end of the caves. The eastern sanctuary serves as the ceremonial entrance.

Fig.4. Linga shrine with four entrances

(Photo courtesy: commons.wikimedia.org)

The chief attraction of Elephanta is the sculptures in the main temple. These are carved in fairly deep recesses in almost full relief. Generally it is best to begin from the first sculptural panel left of the northern entrance, which is now the principal and only entrance, and go clockwise in the same manner as Hindus circumambulate while visiting a temple. As one stands at the northern entrance, the magnificent sculpture of Maheshmurti overwhelms everything else.

Maheshamurti, which is reached through a colonnade of pillars, dominates Elephanta. The following are some details of the sculptures.

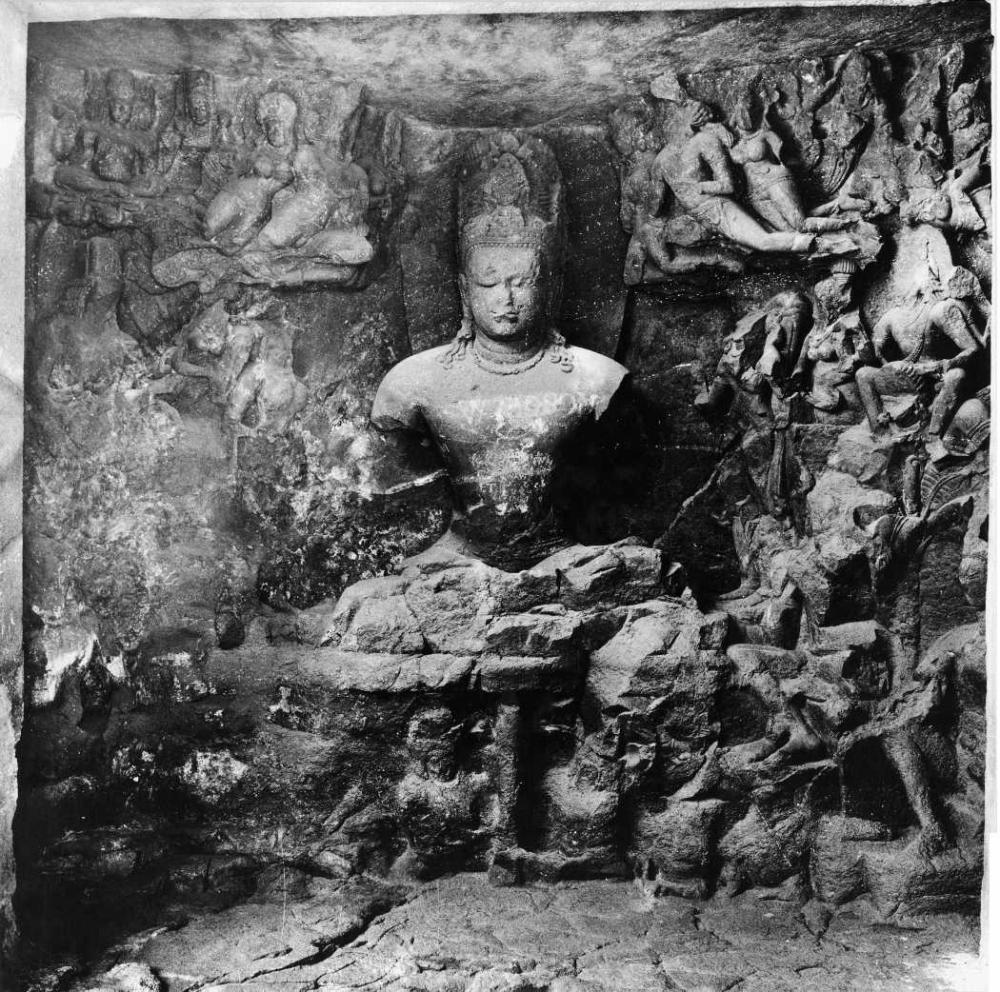

Shiva as Mahayogi - Shiva is seated in a yogic pose, his eyes look practically closed (Fig.5). His crown of matted hair is decorative. His hair falls in ringlets on either shoulder. He wears a necklace of beads. Both his arms are destroyed from near the shoulder and the legs too are destroyed. He is in padmasana (lotus pose) seated on a lotus stalk held by two Nagas. A number of figures are carved on either side of Shiva, including Vishnu and Brahma. As one enters the main temple of Elephanta, this figure is situated on the left. The sculpture has been a subject of much controversy as some identify it as Yoga-Dakshinamurti, while others identify it as Lakulisa.

Fig.5. Shiva as Mahayogi

(Photo courtesy: American Institute of Indian Studies)

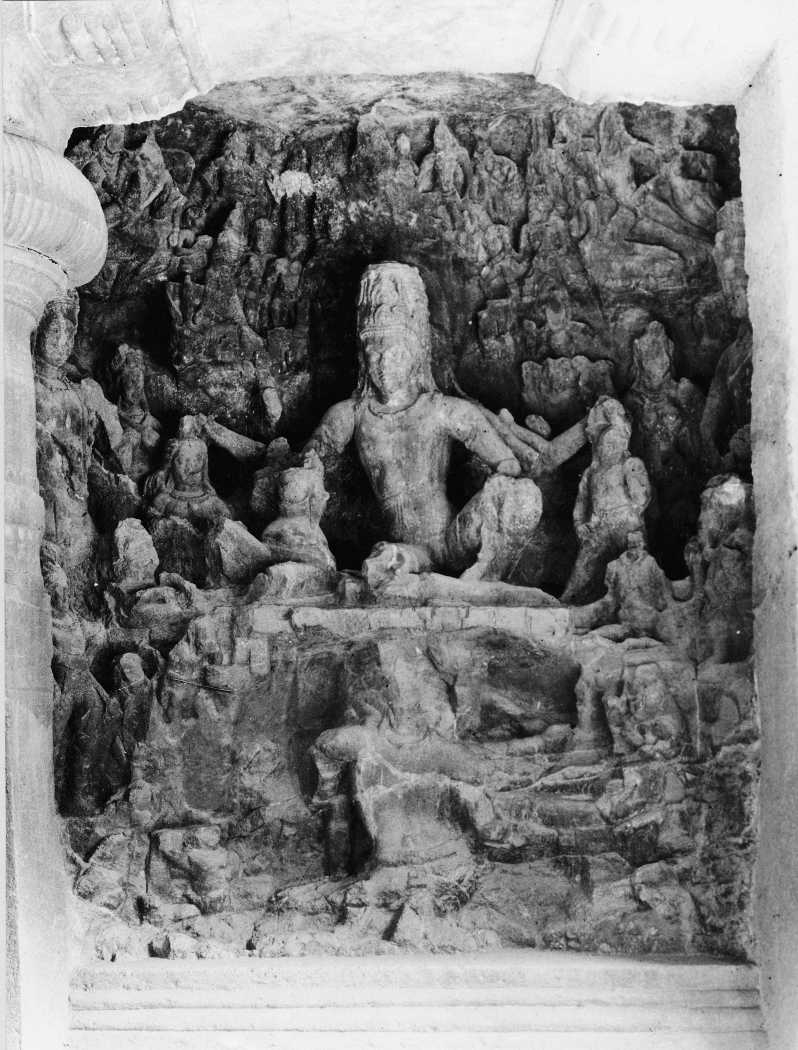

Ravananugraha-Murti - This panel depicts the story of Ravana’s humiliation at the hands of the almighty Shiva and his submission to the Supreme Deity, whereupon Shiva confers a boon upon him (Fig.6). Ravana had humiliated and defeated the powerful Kubera and become the Lord of Lanka. Flushed with his fresh victory, he was flying over the snow-clad mountains of the Himalayas, when he located a beautiful garden and proceeded to go there. However, his vehicle was not permitted to go further as Uma and Maheshvara were engaged in sports. Ravana insulted Nandikeshvara, the leader of Siva’s hosts. Enraged, Ravana then got under the mountain with the intention of lifting the mountain from its base and overthrowing it. He shook the great mountain. Shiva gently put his foot on the ground and Ravana became imprisoned under the snow-clad mountains. Repentant, Ravana praised Shiva. Pleased with his devotion, Shiva conferred a boon on him and presented him with a sword while allowing him to leave.

Fig.6. Ravanugrahamurti

(Photo courtesy: American Institute of Indian Studies, Gurgaon)

This panel is very badly damaged. Uma is seated with Shiva on Mount Kailash, their abode. Maheshwara had originally eight hands. He wears a decorative crown, necklaces, armlets and a waist-belt. His hair falls in curls on either side. His left leg is folded. The figure of Uma is badly mutilated. The Ravanaguhamurti at Kailash in Ellora is far superior to this panel as the panic of Parvati and the other characters present is depicted very realistically.

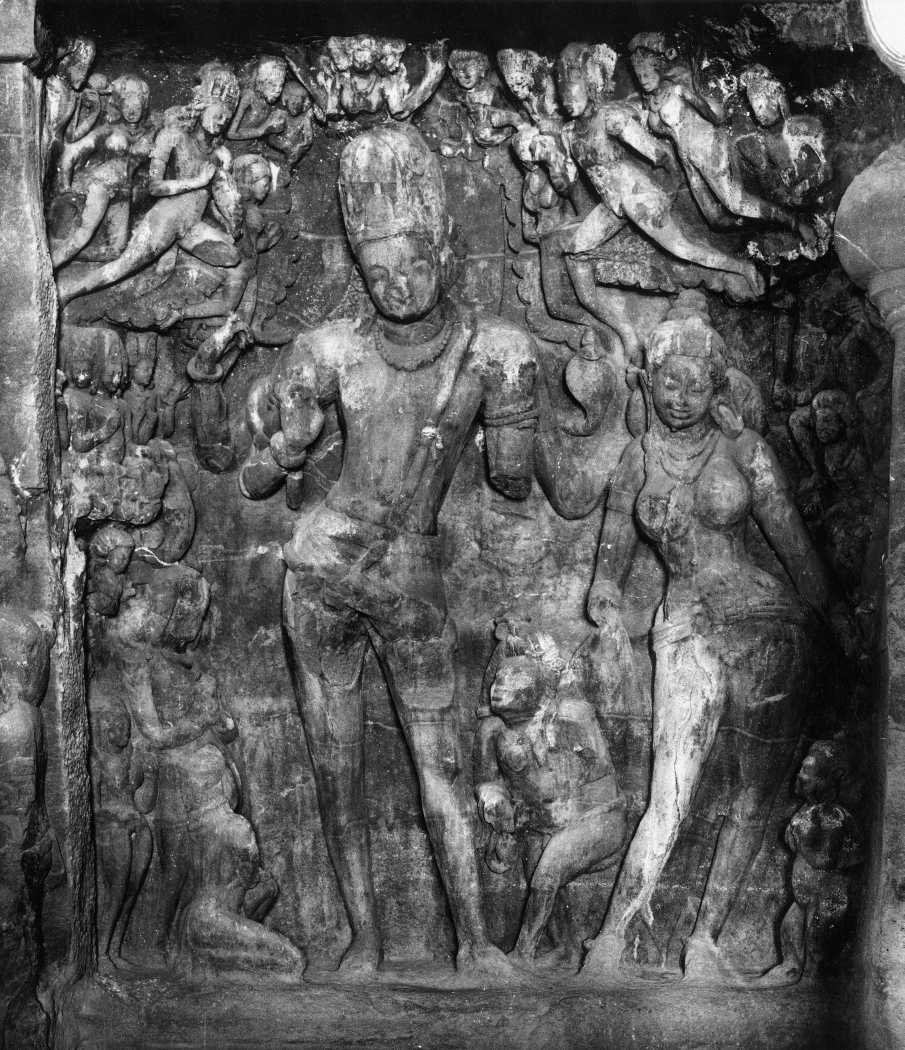

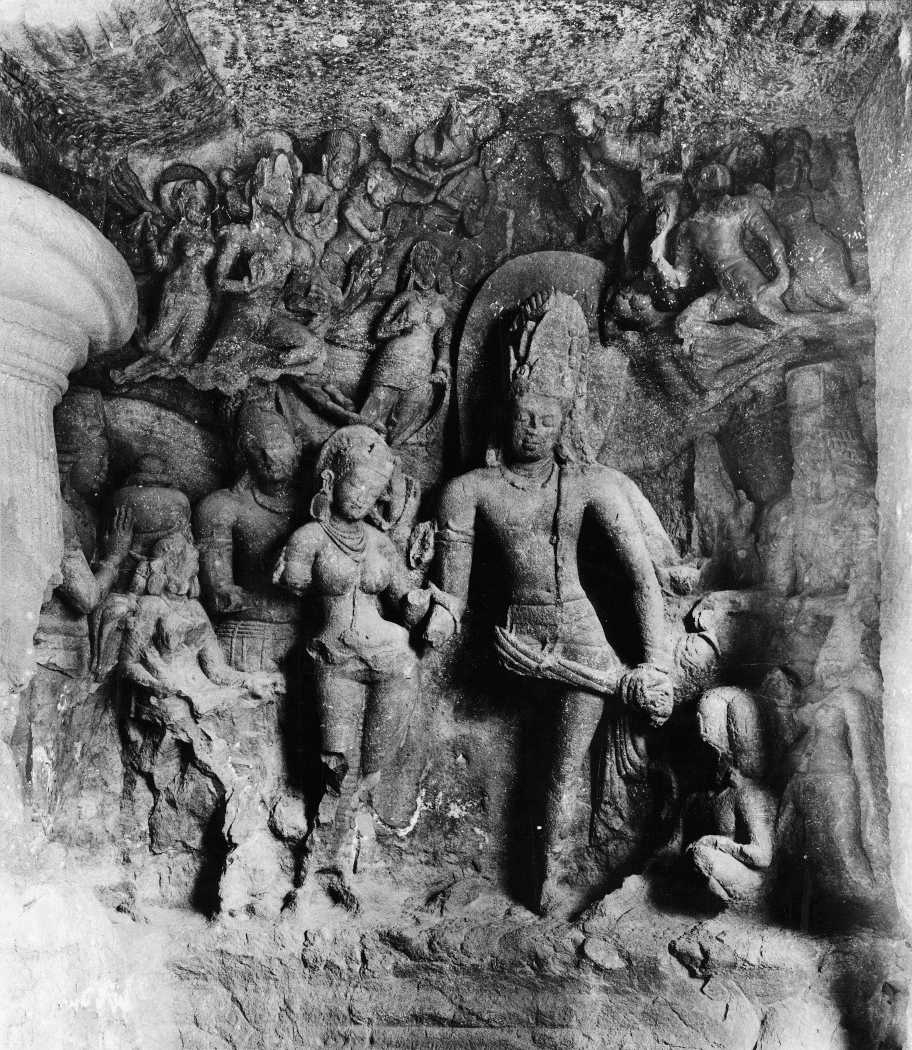

Uma-Mahesvara-Murti - In this panel Shiva and Sakti are emanations of the undivided absolute (Fig.7). Shiva here symbolizes the passive male principle, while Uma or Parvati represents the active female principle, the principle of energy.

Fig.7. Umamaheshvaramurti

(Photo courtesy: American Institute of Indian Studies, Gurgaon)

Unfortunately this panel is in bad condition. Uma and Mahesha are seated in Kailash. Shiva’s countenance is defaced. He sits in the ardha-paryankasana (half-seated posture), reclined to the left. The figure of Uma too is damaged. Below Uma, Nandi and a winged dwarf are seen, while above them are flying figures and male and female attendants on either side.

Ardhanarisvara-Murti - This is the form of Shiva as half man and half woman (Fig.8). It is said that Brahma created the Prajapatis, who were all male, and assigned to them the task of creation. He was baffled when they were unable to do so and promptly proceeded to meet Shiva to seek counsel for this problem. Shiva appeared before him in the form Ardhanavisara, half man and half woman. Brahma immediately realized his error and created a woman.

Fig.8. Ardhanarishvaramurti

(Photo courtesy: American Institute of Indian Studies, Gurgaon)

In another story with a similar theme, sage Bhringi refused to worship Parvati and only worshipped Shiva. Parvati undertook severe austerities and became one with Iswara (Shiva), but still Bhringi only circumambulated Iswara. Parvati incensed rid Bhringi of his flesh and blood and turned him into a skeleton. He could not stand and Shiva in compassion gave him a third leg. Eventually, Shiva helps them reconcile while emphasizing the unity of the male-female principles.

The Elephanta Ardhanarisvara looks elegant and impressive. The four-handed Ardhanarivsara stands majestically on Nandi. The left half of the sculpture, which represents Parvati, has a breast, exaggerated rounded hips and is shown holding a mirror. On the right side, Shiva’s crown has a crescent and his body is more muscular. He holds a cobra in his hand. There are a number of other interesting figures in the panel of various divinities seated on their mounts: Indra is seated on Airavata, Brahma on a lotus, Varuna on a crocodile, Kartikeya on a peacock and Vishnu on Garuda. This is one of the most unique panels in terms of its grace and perfect balance.

Maheshmurti - Right in the center, as one enters the cave temples, is one of the grandest compositions of Elephanta, the Maheshmurti (Fig.9). Shiva here is portrayed as the creator, protector and destroyer. The right half-face is benign, peaceful and feminine, depicting Shiva’s aspect as a creator. The central face shows introspection and reveals the protective aspect. The left-half face is hideous, displaying great anger. It symbolizes his power to dissolve the universe. The three aspects of divinity are combined in one.

Fig.9. Maheshamurti

(Photo courtesy: American Institute of Indian Studies, Gurgaon)

This sculpture is majestic not only in its conception but also in its size: it stands tall at 18 feet. The central bust wears a decorative crown. The coils of matted hair are held within this elegantly carved crown. The chief element is its kirtimukha decoration, a typically Chalukyan element. The whole crown is adorned with elaborate jewelry comprising of pearls and diamonds. On the right side of the crown is a half moon. Kirtimukha is a special emblem of Shiva believed to be guaranteeing the true devotee with peace.

The central face of the deity is executed in very high relief. The other two side faces appear to recede in the background compared to it. The sculpture represents Mahadeva, the Great Lord as Tatpurusha, Aghora and Vamadeva.

Gangadhara–Murti - Next to the Maheshmurti is the Gangadhara-murti panel, which narrates the story of the descent of the river Ganges from heaven to the earth (Fig. 10). The king Bhagirath practiced severe austerities to win over the river Goddess Ganga, to persuade her to leave her heavenly abode and descend on the Earth. Ganga was pleased and agreed to leave her celestial abode but requested Bhagirath to persuade somebody to receive her fall, as otherwise the force of her descent on the earth would split it in half. Bhagirath again undertook severe penance to persuade Shiva to receive the powerful descent of the waters of the mighty river. Shiva was pleased and granted his request. To humble Ganga, who fell with great force, Shiva made her wind through his matted hair—which is symbolic of the variegated universe—thus, preventing her from descending. Bhagirath once again prayed to Shiva, requesting him to allow Ganga to come down to the earth. Emerging from Shiva’s locks, Ganga finally falls on the earth.

Fig.10. Gangadharmurti

(Photo courtesy: American Institute of Indian Studies, Gurgaon)

In sculptural form Ganga appears in the matted hair of the mighty Shiva. Because Ganga descended on the earth due to Bhagirath’s severe austerities, she is called Bhagirathi, the daughter of Bhagiratha. In the Elephanta panel, Shiva is seen standing with the right leg reclined. His left leg is bent a little at the knee. Shiva is of tall stature and slim body. His torso is inclined to the left. Over the head of Shiva are three heads representing the three sacred rivers of India, Ganga, Yamuna and Saraswati. Shiva has four hands. On the left of Shiva, Parvati stands gracefully in the tribhanga pose. Her diaphanous lower garment is held in place by a girdle. She wears a simple crown and a few select ornaments.

This is one of the most beautiful panels at Elephanta. It is a masterpiece composition. The main attraction are the figures of Shiva and Parvati. There is a rhythm which binds these two figures together in a harmonious whole.

Kalyanasundara-Murti (Marriage of Shiva-Parvati) - According to the Shanti Parva of the Mahabharata, the main character Daksha, one of the twelve Prajapatis, performed a great sacrifice to which all the gods were invited except Shiva, his son-in-law, the husband of his daughter Sati. This angered Sati, who insisted on Shiva’s attending the sacrifice, but Shiva declined. Sati then went to the sacrifice alone but was humiliated by her father, following which she jumped into the sacrificial pit. When the story of his wife’s humiliation reached Shiva, he was inconsolable and created the terrible Virabhadra, who destroyed Daksha’s sacrifice and made him supplicate to Shiva.

Sati was reborn as the daughter of Himavan and Menaka, and once she came of age she began to practice penance to be blessed once again with Shiva as a spouse. Shiva was engaged in severe austerities. At the time the asura Taraka was getting stronger and becoming a menace to the gods. It was said that he would be destroyed by Shiva’s son. So Shiva had to be persuaded to give up his austerities and get into wedlock. Kamadeva was entrusted with this task. As he was the God of Love, he used his arrows on Shiva successfully. Shiva opened his eyes and saw Parvati, and the marriage was celebrated with great ceremony. Brahma acted as the sacrificial priest, and Vishnu and Lakshmi gave Parvati away in marriage to Shiva.

The marriage of Shiva and Parvati is beautifully delineated at Elephanta (Fig. 11). The figure of Parvati looks young, charming and full of joy and contentment. She is shown as a traditional young bride with her head bowed down. Adding to her charm is the small crown she wears and the stanahara (a stringed necklace). The figure of Shiva is well-matched to that of Parvati. He looks young, tall, slim and well-formed. He wears a simple crown and his curly hair falls on his shoulders.

Fig.11. Kalyanasundaramurti

(Photo courtesy: American Institute of Indian Studies, Gurgaon)

Brahma, as a priest, sits on the left of Shiva, close to the sacrificial fire. Vishnu is seen behind. Parvati’s father Himavan is just behind her. Close to him stands a very graceful figure, who is probably Menaka. There are several other figures attending the divine marriage including the flying figures above.

Andhakasuravadha Murti (The killing of the Demon Andhaka) - This theme of the Lord Shiva killing the demon Andhaka is popular even at Ellora . The story goes that the demon Andhaka who had become extremely powerful and was harassing the gods, had heard about the beauty of Parvati and cultivated a desire for her. He dispatched a demon Nila to kill Shiva. Nila assumed the form of a huge ferocious elephant to fulfill his task. Virabhadra, the mighty son of Shiva, slayed him and presented the elephant skin to his father. Shiva, joined by Vishnu and others, united in battle against Andhaka. However, Andhaka had special power that created a problem for Shiva. Out of every drop of his blood that would spill in the battle, another demon would come to life. To solve this problem Shiva created Yogesvari and each God created his respective Shakti (Brahma-Brahmani, Vishnu-Vaishnavi, Varaha–Varahi etc.) and in this way the Saptamatrikas (seven divine mothers) were created. They drank up the demon’s spilt blood. Vishnu killed all the subsidiary demons and when Shiva was about to kill Andhaka, the demon begged for forgiveness and thus obtained his pardon and grace. Shiva made him commander of his ganas (attendants) and he was named Bhringisha or Bhringirishi.

Andhaka’s blindness is symbolic and emphasizes the superiority of knowledge over ignorance and darkness. In the Elephanta panel Shiva is seen in an aggressive mood. His whole stance gives the impression of belligerence (Fig.12). Unfortunately, both the sculpture’s legs are broken. His jatamukuta shows a skull, cobra and a half moon. The eyes seem to protrude out of the sockets while the third eye is open in anger. The hair falls on his shoulders. He wears a decorative necklace, armlet and a mundamala (a garland of skulls). He has eight hands. The elephant Nila is seen on his right. Virabhadra is seen presenting the elephant skin. A sword is held in a threatening manner in the right hand. In one left hand is held a skull cup for Andhaka’s drops of blood. A number of flying figures carrying offerings are carved. An object in the centre looks like a stupa with an umbrella. The flying couples on the sides are beautifully carved.

Fig. 12. Andhakasurvadhamurti

(Photo courtesy: American Institute of Indian Studies, Gurgaon)

Nrittamurti Shiva - Shiva is the divine master of dance. In Bharata’s Natyashastra where 108 kinds of dance poses are listed, Shiva is proclaimed as the Nataraja, or king of dance. Dance is almost like a form of magic in its ability to transform the personality of the dancer, who appears to be possessed by supra-terrestrial powers in the process. Like yoga, dance induces ecstasy, the mergence with and experience of the divine. Dance is considered to be an act of creation.

Fig.13. Nrttamurti

(Photo courtesy: American Institute of Indian Studies, Gurgaon)

The dancing figures of Shiva as Nataraja are some of the most attractive manifestations of the Indian art tradition. The dance posture depicted at Elephanta is what is described as lalitam (Fig. 13). The figure’s legs are broken as are some of the hands. Though the figure is mutilated, it has not lost its charm. The figure pulsates with life and movement, and has a rhythm and grace which even the broken limbs are not able to conceal. The face which is slightly tilted towards the left hand adds further charm to the figure. A number of musicians are shown seated around Nataraja, though in a damaged condition. The figure of Parvati also looks graceful. Other gods seen are Brahma, Ganesha and Kumara. Besides these there are other smaller panels of Kartikeya, Matrikas, Ganesa, Dvarapalas, etc (Figs. 14a- 14g).

Fig.14a. Kartikeya panel (Photo courtesy: American Institute of Indian Studies, Gurgaon)

Fig.14b. Matrika figures (Photo courtesy: American Institute of Indian Studies, Gurgaon)

Fig.14c . Matrika figures (Photo courtesy: American Institute of Indian Studies, Gurgaon)

Fig.14d. Matrika figures with Ganesha (Photo courtesy: American Institute of Indian Studies, Gurgaon)

Fig.14e. Ganesha (Photo courtesy: American Institute of Indian Studies, Gurgaon)

Fig.14f. Dvarapala (Photo courtesy: American Institute of Indian Studies, Gurgaon)

Fig. 14g. Dvarapala (Photo courtesy: American Institute of Indian Studies, Gurgaon)

Cave 2 is located to the southeast of the Great Cave. It faces east and has a shrine at its northern end. The cave has four pillars and is badly damaged. Traces of sculptures still remain. The damage was caused by the heavy monsoons in the region, especially due to the resultant accumulation of water.

Cave 3 is towards the south of Cave 2 with six columns and two pilasters visible at the entrance. These pillars are in fairly good condition as they have been reconstructed. The veranda is 80 meters in width and 35 meters in length. At the north end of the veranda is a large raised chamber supported by four octagonal pillars and two pilasters. The capitals of these pillars are similar to those in the main cave though with one difference. The amalaka or cushion member here looks compressed. The dimensions of the chamber are impressive. It is 11.9 meters in width and 6.7 meters in depth. The walls of the chamber are bare.

Cave 4 has a plan that is similar to Cave 3. The veranda is 15.2 meters in breadth. Carved into the back wall are three cells and a linga shrine. The shrine is 5.7 meters in width and 6 meters in depth. The dwarapalas (gatekeepers) that once existed here have now disappeared. On either side of the veranda are chambers which are 4.6 meters square in area. Each of them are supported by two pillars and two pilasters. The doors of the side chamber shrines have chaitya ornamentation.

In front of these caves is a ravine that one needs to cross and ascend to a height of about 30 meters to reach caves 5 and 6 which are located in the eastern hill. Cave 5 has a veranda and a shrine with a yoni and linga. Cave 6, further north-east, appears to be unfinished.

Shrine in the East wing - In the east wing of the main cave is another shrine similar in plan to Ramesvara (Cave No.21) at Ellora. There are also sculptures of Ganesha and Saptamatrikas.

West Wing - There is a chapel in the west wing. In the veranda is a sculpture of Shiva as a yogi (Fig.15). To the south of the linga shrine is a six- handed dancing figure of Shiva accompanied by Vishnu riding Garuda, Yama on his buffalo and Brahma (Fig.16). They are now in a damaged condition.

Fig.15. Shiva as Yogi

(Photo courtesy: American Institute of Indian Studies, Gurgaon)

Fig.16. Shiva accompanied by Vishnu, Yama and Brahma

(Photo courtesy: American Institute of Indian Studies, Gurgaon)

Conclusion

The small island is dotted with numerous archaeological remains that are testimonies to its rich cultural past. These archaeological remains provide evidence of occupation from as early as 2nd century B.C. The site calls for further excavations to unearth new historical material, especially on the buried stupas. This will help fill in many of the historical lacunae around this unique and awe-inspiring monument.

References

Brown, Percy. 1959. Indian Architecture: Buddhist and Hindu periods. Bombay: D.B. Taraporevala Sons & Co. Private Ltd.

Burgess, James. 1903. Rock Temples of Elephanta. Archaeological Survey of Western India. Vol. IX. London

Fergusson, James and Burgess, James. 1880. The Cave Temples of India. London

Gupte, R.S. 1965. “The Dating of Elephanta Caves”. Journal of Indian History, Vol. XLIII Part-II

Mirashi V.V. 1966. Kalachuri, Nripati ani Tyancha Kala. Nagpur

Rowland, Benjamin. 1959. The Art and Architecture of India: Buddhist. Hindu. Jain. Penguin Books

Sastri, Hirananda. 1934. A Guide to Elephanta. Delhi

Spink, Walter. 1938. “The Great Cave at Elephanta: A Study of Sources" in Essays on Gupta Culture ed. B. Smith and E. Zelliot. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass

Spink, Walter. 1967. “Ajanta to Ellora”. Marg. Vol. XX. No.2. Bombay (Mumbai)

Spink, Walter. 1975. “Ellora’s Earliest Phase”. Bulletin of the American Academy of Benaras. Vol-I

Qureshi, Dulari. 2010. The Rock Cut Temples of Western India. New Delhi: Bharatiya Kala Prakashan

Internet sites:-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elephanta_Caves.

http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/244

http://www.virtualtourist.com/travel/Asia/india/state-of Maharashtra-Elephanta-island

www.sacred.destination.com/India/elephanta caves