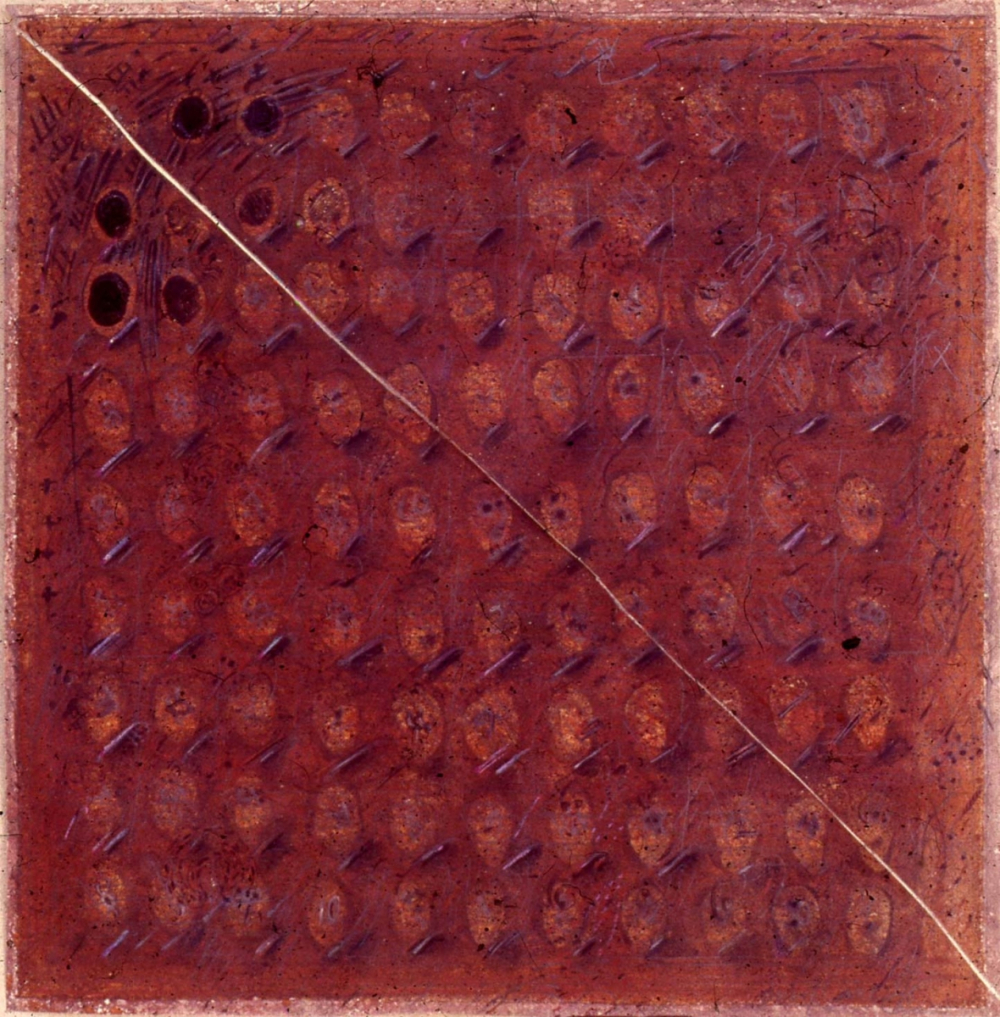

Figure 1: 'Echo'; 2' x 2'; mixed media on paper; 1986

C. Douglas (b.1951) is the rarest of the rare Indian modernist artists who can capture his emotions in lines, colours, abstractions, and figurative allegories. Writing about Douglas’ early works, art critic Josef James records that instead of drawing and then colouring his works, Douglas went on to find abstractions with patterns, rhythms, and structures through brush strokes and colour values. The formal devices in his paintings, the grids, triangles, frames and horizontal lines had a rigorous and rigid formal beauty (James 2004a:115–22). When he was a student in the Madras College of Arts in the 1970s, Douglas would say that he learnt his draughtsmanship from his friend, K. Ramanujam, the principle of exposing the line from his teacher Santhanaraj, and the ideas of Madras movement from K.C.S. Paniker with whom he moved to the Cholamandal artist’s village. Josef James further records that, 'The disorientation, hurt, and pain started register in Douglas’ paintings towards the end of his nine-year stay in Europe in the '80s.' (James 2004b:118) Douglas' formal structures loosened up giving way to create multi-textured surfaces. Crumpled papers, canvasses washed many times, red mud mixed with Fevicol used as a colouring agent, and papers pasted on canvas are a few of the techniques Douglas uses in his mixed media works. Grey, mud red and black have become Douglas’ hallmark colours after his return to Cholamandal, and his extended liminality made him brave with his decidedly picturesque works.

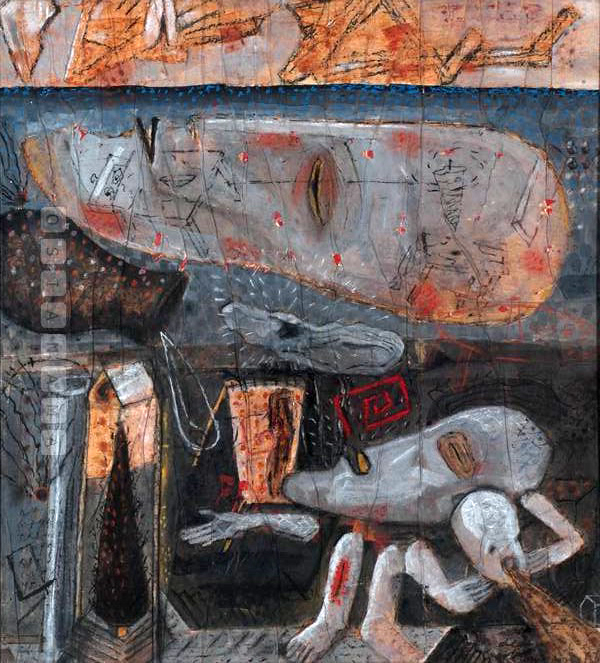

Douglas' early work Echo (Figure 1) is a fine example of his workmanship and a demonstration of the formalistic elements that would constitute his personal legend and the visual vocabulary of his later works. Diagonally divided by a white line Echo is an earthy, brownish red mixed media work on paper in which one triangle more or less reflects the pattern on the other. It is not a mirror reflection; it is an echo effect and as such, there is a subtle distortion of the round patches and the nail-like protrusions from one side to the other. The highly textured surface of Echo is a pictorial trait Douglas would carry to other artworks as well. The obsession with formal structures and the orderly world they evoke could have been the wish fulfilment the artist desired on his return to Cholamandal after his sojourn in Germany. Echo is also a pure pictorial form, in the sense that it does not have any real world representation. The checkered patterns and sharply edged colours highlight the diagonal division and make us wonder about the nature of echo itself. We see a similar experimentation with textured surfaces and pure pictorial form in Figure (Figure 2). A large gaping wound like a hole that could have been in the bark of a tree stares at the viewer in an alluring way. It is a trace, memory, a permanent reminder of pain suffered in the past and it stays surrounded by the sutures of time.

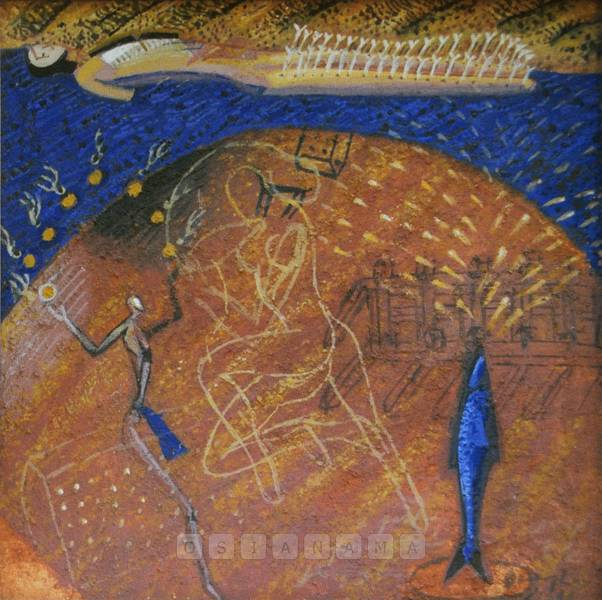

In the decade of 1985 to 1995, we see Douglas transitioning into figurative abstractions. In another painting titled Figure (Figure 3), we see a figure tied and entrapped in a cylindrical structure.

Figure 2: 'Figure'; 3 feet x 2 feet; mixed media on paper mounted on cloth; 1993

The hollowness of the cylindrical structure stands exposed evoking T.S.Eliot's famous lines:

We are the hollow men

We are the stuffed men

Leaning together

Headpiece filled with straw.

Like Eliot's hollow men, Douglas' Figure also exhibits a 'paralysed force', and stands like a modern man in a 'gesture without motion'. As an avid reader of modernist poetry and philosophy Douglas continuously registers their influence in his visual lexicon which is both a personal artistic statement as well as critique of our times. The seamless integration and evocation of modernist poetry and philosophy is another definitive feature of Douglas' works that takes root in this period. Chronicling Douglas' evolution as an artist during this decade, Joseph James wrote, 'His metaphor for this in his work of that period was the foetus, the prenatal condition in which there is neither separation nor participation of any kind. His ability to flight the line and to freely make figures with it was at play in the fragile personal myth he tried to hazard in the drawings of that period' (James 2004c:116). Douglas would happily quote Fernando Pessoa’s lines, 'Perhaps my destiny is to remain forever a bookkeeper, with poetry or literature as a butterfly that alights on my head, making me look ridiculous to the extent it looks beautiful' (Pessoa 2003).

Douglas would characterise his refuge into poetry and philosophy as the result of a double exile he experienced living in the Cholamandal Artists' Village. While his shifting to Cholamandal confirmed his career as a full-time painter and provided the companionship of other artists to him the fact that Cholamandal was still in its early stages of development, and it was isolated from the mainstream society ensured his liminality. Cholamandal, the coastal village south of the city of Chennai, was also haunted by the suicide of the talented artist K. Ramanujam with whom Douglas shared a special friendship. Ramanujam was a strange cartographer who would draw fantastic cities and crystal worlds that inhabit architectural patterns imitative of traditional temple pillars and reliefs. The way Ramanujam could play with his lines and make patterns out of them made a strong impact on Douglas. In a documentary dedicated to the life and works of Ramanujam Douglas says how Ramanujam's personal graphic style would draw the viewer into its world. Ramanujam's personal world found an echo in Douglas' personal experience of alienation and displacement and he found Eliot's Wasteland and Camus's L'Etranger providing maps for his maplessness. The ceramic sculpture titled the Bell (Figure 4) came to represent his isolation and the impossibility of human communication.

Figure 3: 'Figure'; 6 feet x 4 feet; mixed media on paper mounted on cloth; 1993

Figure 4: 'Bell'; Ceramic Sculpture; 1994

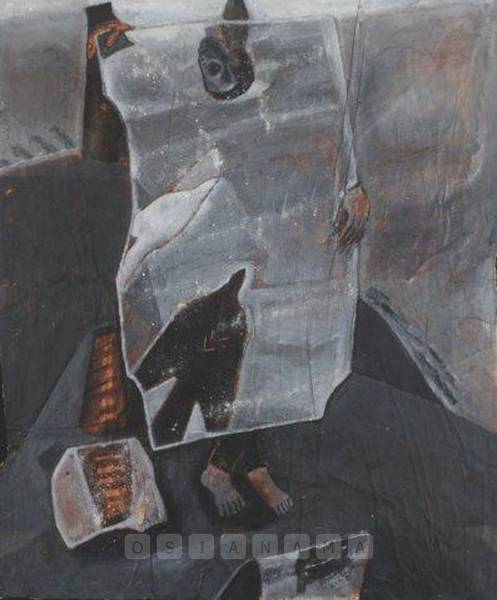

Figure 5: 'Untitled'; 4 feet x 3 feet; mixed media on paper ;1995

Of all the pictorial elements Douglas came to rely on the lines, figures and textured surfaces to construct his paintings. During his decade-long stay in Germany, Douglas was greatly influenced by the works of new Expressionists like Anselm Kiefer and Wols (Alfred Otto Wolfgang Schulze) and he would say, 'Sometimes, I like to use the sand as a texture for my work, or tea stains, or tear the paper, or walk over, crumple it up, which is why I prefer to work on paper or any fragments that are there to create my own surface.' Perhaps the man with bandages on his head in Douglas’ series, Missed Call is a distorted self-portrait of the suffering and sensitive person he is, although he would pass the question why he has not done self-portraits at all. To a pointed question by Ashvin Rajagopalan, 'Who is the man with bandages in your works?' in the book Missed Call: C. Douglas, The Mind of an Artist, Douglas says, 'It is a historical reference to Van Gogh and Bhupen Khakar’s, Man with Cold painting. Like the woman with a bandage on her lips is a reference to an advertisement, Speak Easy, that teaches people spoken English. You feel some silence when you miss a call. One may not feel fractured or mutilated when you miss something you just keep on living' (Rajagopalan 2008a:58).

The mutilated and hollowed living finds many expressions in Douglas’ paintings; human figurines spread on the ground pierced by arrows, cripples on wheelchairs, the blind poet, broken mannequin, and the fragmented bodies that ooze different fluids. 'The void, the hollowness, the endless emptiness within all of us,' Douglas would say, 'The spaces between the ladder, the void within the telephone receiver, the eye of the needle are all essential symbolic hollowness within us'. Since he seeks to present our inner fragmentation, he adopts figurative and abstract styles of painting. The angular faces that look like skulls, stick-like figurines that appear to have jumped out of tribal wall paintings, and one-dimensional human bodies populate his paintings. Despite the muddled and crumpled surfaces, the paintings acquire certain luminosity and depth. We see a darkness behind the mask as a face in an untitled painting (Figure 5) where the interplay of the surface and the background suggest a profound emptiness.

Underneath the stream of suffering and pain, there is a secret undercurrent of a spiritual journey that flows through, and it consists of Zen poetry, Ramana Maharishi’s silence, and unheard melodies. It is the call of a bell men would ignore as Douglas depicted in his ceramic sculpture in 1994 (Figure 4). The bell and a man cupping his ears form a repeated motif in Douglas’ works. Sometimes, the bell does not have a clapper. Douglas quotes Francesco Clemente who went in search of Shiva’s brass bell that is hand-crafted and sold in Varanasi. Clemente found out that Shiva’s bell does not have a clapper; it has to be heard internally. It is like one hand clapping, imagery we come across in Zen poetry, Douglas would muse.

In Absence (Figure 6) and two other untitled paintings (Figures 7 and 8) lines acquire prominence and create visual depth. Perceiving visual depth in his paintings is a viewer act since Douglas creates everything on the surface, a non-hierarchical space. Absence very clearly evokes Derrida's critique of the metaphysics of presence which introduced a play of absence and presence (Derrida 1997). In the presence of angular mask-like faces in Douglas' painting, what is missing and absent is the significant other. The communication between the angular faces is also missing, and they do not see or hear each other. This is not a case of people experiencing extreme forms of loneliness, but it is a kind of sickness. By recognising the absence of the 'other' as sickness, Douglas escapes the infamous Sartrean dictum 'the other is hell'.

Figure 6: 'Absence'; 3 feet x 3 feet; mixed media on paper mounted on cloth; 1997

In conversation with Ashvin Rajagopalan, Douglas says, 'In contemporary theory, they say that a healthy, wealthy man has several identities. In stark contrast, the sick man (who is mentally ill) has only one identity. He forgets about the 'other'. He stays in contact with himself by the smells of the body. He stops changing his clothes. He almost starts wearing a uniform. The bad odour of his could be interpreted as the smell of himself so he forgets what is 'difference', what is the 'other'. But he is not clinically schizophrenic' (Rajagopalan 2008b:47). In another untitled painting (Figure 8) even lovemaking between the two figures stands intercepted by a series of spikes.

Figure 7: 'Untitled'; 3 feet x 4 feet; mixed media on paper mounted on cloth; 1998

Douglas' figures adopt different poses and stances in his paintings. They are invariably nailed or pierced. So the figurines in Douglas' paintings generate their own reality. In his notebooks, Douglas has underlined a passage from Baudrillard's Simulacra and Simulations and writes, 'We manufacture the real because of simulation. So once again we find that the real is not so much given as produced which basically means we cannot win. This is why the relationship between the real and representation is not inverted; images precede the real. The logical order of things might be that reality expresses itself through representation, but this has been turned upside down' (Rajagopalan 2008c:42, Baudrillard 1994). By continuously painting the inner realities of human existence, Douglas despaired to transition into Baudrillardian simulation where the simulacrum has no relationship to any reality whatsoever. Alternatively, rather, there is only a reality of images. A specific analogy that Baudrillard uses is a fable derived from On Exactitude in Science by Jorge Luis Borges. In it, a great Empire created a map that was so detailed it was as large as the Empire itself. The actual map was expanded and destroyed as the Empire itself conquered or lost territory. When the Empire crumbled, all that was left was the map. In Baudrillard's rendition, it is conversely the map that people live in, the simulation of reality where the people of Empire spend their lives ensuring their place in the representation is properly circumscribed and detailed by the map-makers; conversely, it is the reality that is crumbling away from disuse. Douglas would say half-jokingly, 'We will all die looking at our photographs.'

Figure 8: 'Untitled'; 3 feet x 4 feet; mixed media on paper mounted on cloth; 1999

How does he respond to the hyper-reality of images? The incorrigible romantic he is, he does have many figurines dancing in ecstasy in many paintings such as the untitled paintings Figure 7 and Figure 8. Increasingly there are no women in his paintings. If at all there any women as we find in his series Missed Call he would not know who they are. To a query on who is the woman in his works, he replies, 'I don't know. It is only a woman. May be women wait a lot. That is something that has occurred to me. They wait for their children and husbands. May be waiting is much more a part of women than men. When we think about Buddha's wife, she waited for him after he left. Men go away; they are soldiers. The women keep the house running and wait with food' (Rajagopalan 2008c:38). Roland Barthes recounts a tale about waiting in his A Lover's Discourse Fragments, 'A Mandarin fell in love with a courtesan. "I shall be yours", she told him, "when you have spent a hundred nights waiting for me, sitting on a stool, in my garden, beneath my window." But on the ninety-ninth night, the Mandarin stood up, put his stool under his arm, and went away' (Barthes 1978:40). In Douglas' paintings, the waiting is never over, and there seems to be no exit.

Figure 9: 'Exit'; mixed media on paper; 2002

In 'Exit' (Figure 9), the human figure lies frozen on the threshold, and another figure dances on it haphazardly. Typical of Douglas' paintings, drawn in earthy mud brown colour it reminds one of the people who have never passed the gate of hell for not understanding their fellow men who suffer.

Figure 10: 'The Boat'; mixed media on paper mounted on cloth; 2005

It does not mean the figures in Douglas' paintings do not attempt to leave or dream of leaving. In Boat (Figure 10) a bedridden boy devoured by a demon watches a boat being rowed away. The window frames the boat in such a way to suggest a one-eyed mask. The painting is intriguing in its multiple imageries and complexities. The greyness of the painting is striking, and it almost gives a foreboding of its dominance in Douglas' paintings later. In Ferry (Figure 11) we recognise that an instrument of crossing and journeying is a metaphor for the desire to leave but never to reach. Ferry depicts a pierced body floating over a castle-like structure only to plunge headlong into a squarish hole. A boat and a chair are there sideways of the plunging body as if they were left out of choice. One notices the way The Boat (Figure 10) and Ferry (Figure 11) converse with each other in a muted narrative: one depicting a desire to leave and another specifying the hellish destination.

Figure 11: 'Ferry' 1.5 feet x 1.5 feet acrylic on canvas 2008

It is not a completely pessimistic outlook but rather a concern for the other because there is no reason to believe the human figures in these paintings are the personae of the painter. Ferry in fact evokes the lines of Marina Tsvetaeva who wrote, 'Ah, night. Small rivers of water rise and bend towards—sleep. (I am nearly sleeping). Somewhere in a night, a human being is drowning' (Tsvetaeva 2009).

Figure 12: 'Man with mirror'; 3 feet x 4 feet; mixed media on paper mounted on cloth; 2010

It is the concern for the other, for someone else drowning that is central to Douglas' art and thinking. Exploring new grounds of figure-ground relationships, Douglas presents haunting images of fragmentation. Man with Mirror (Figure 12) is an excellent interrogation of the inner fragmentation. The mirror in the Man with Mirror is a transparent broken glass through which we see a distorted face, a pair of feet, and the hands hugging and holding the glass. There is another glass reflecting the man holding the glass and showing a vague silhouette of a face. There is one more mirror in the background that appears to be a window. There are two bodily parts randomly thrown on the floor, one of which is kept in a glass case. The mirror in the hands of the man depicts two bird-like creatures one black and another white with their beaks pointed towards the man. Man with Mirror is a title that evokes Narcissus who is engrossed in his self-image, but in a Baudrillardian world of hyper-real images, the self-image of anyone seems to be entirely broken and fragmented through a range of reflections. Douglas has executed this painting in grey and shades of black and these colours add grimness to the canvas.

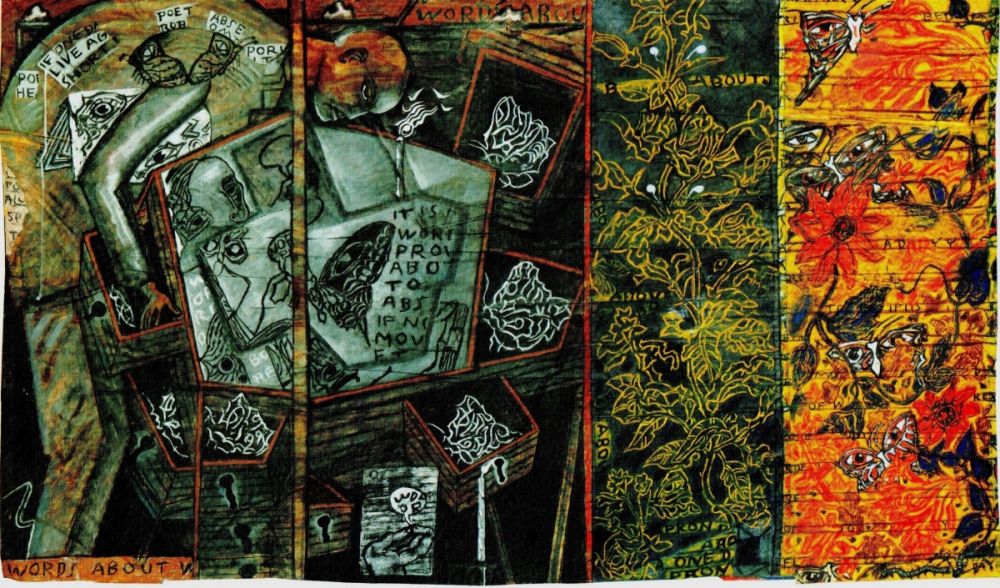

Figure 13: 'Blind Poet & the Butterflies I'; 36 x 60 inches; mixed media on paper mounted on canvas; 2011

The metaphor of the fragmented self and maimed body assumed new exposure when Douglas presented a new series of paintings titled Blind Poet & the Butterflies in 2011. Filled with etchings of letters on to the images of colourful panels Blind Poet & Butterflies is a great series that hides Douglas' characteristic grimness and moroseness. Considering the fact that the world's greatest poets such as Homer and Milton are blind, Douglas' blind poet wanders through his canvases of colourful patterns of butterfly wings and floating words. The series is filled with dark ironies and intertextual references to poetry and philosophical texts.

The lepidopterist of the poet stands bent over a mummified butterfly in a glass box with his blindness while the live butterflies fly all over in riotous gold and red (Figure 13). Is that a statement on the failure of visuality and the celebration of the imagination aided by words?

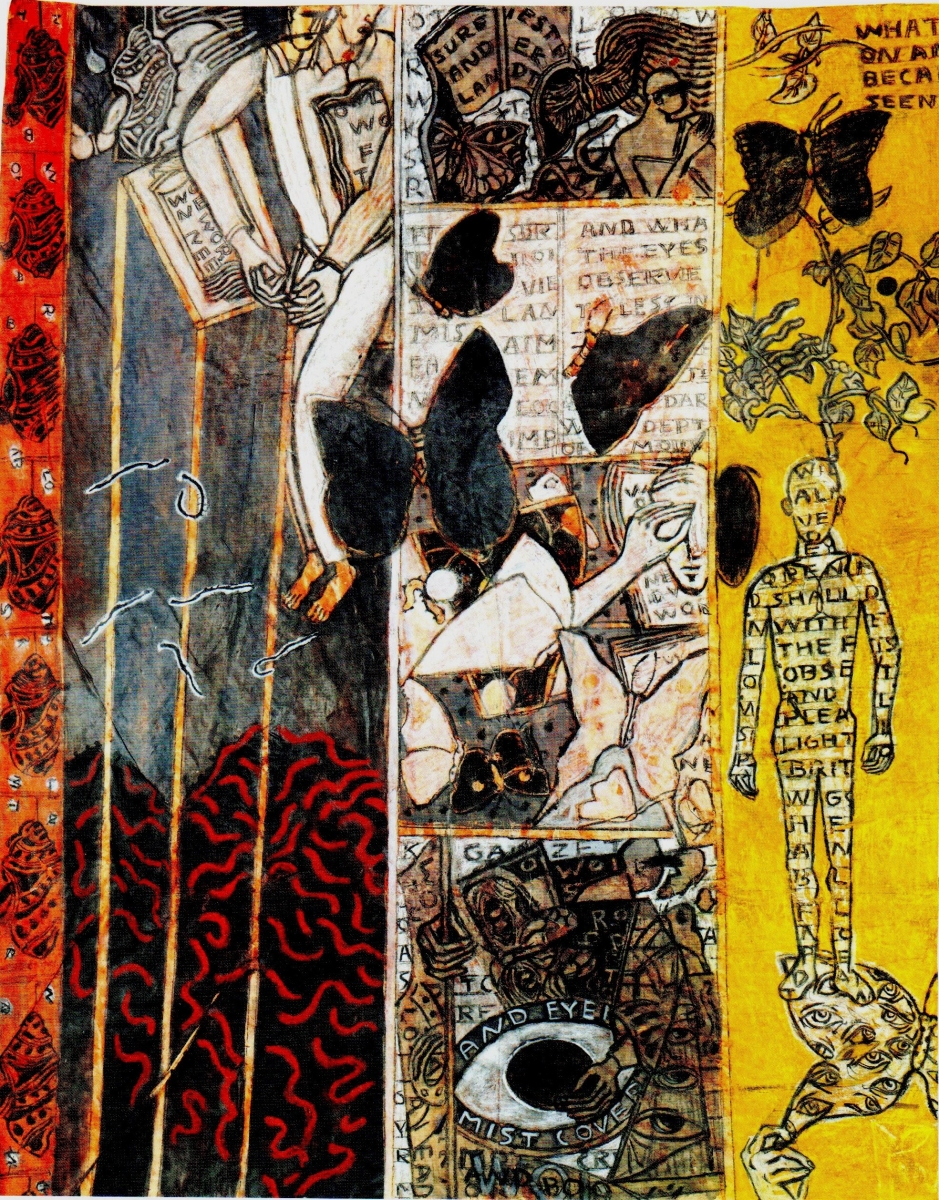

Figure 14: 'Blind Poet & the Butterflies II'; 53 x 41 inches; mixed media on paper mounted on canvas; 2011

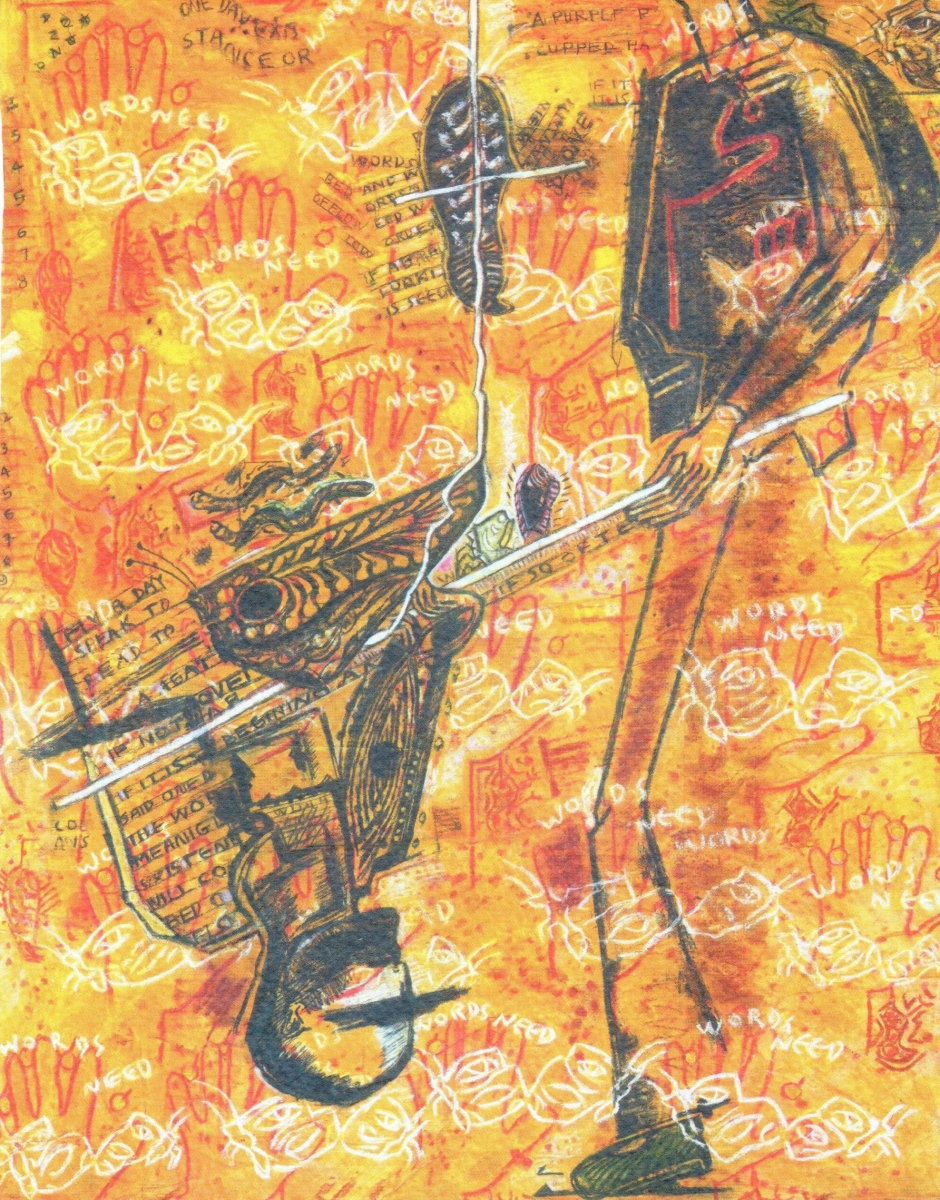

Douglas' series has an oblique reference to Derrida's book, Memoirs of the Blind: The Self-Portrait and other Ruins. Derrida's book was a response to a request by the Louvre Museum that had inaugurated a series of exhibitions where well-known authors were invited to organise an exhibition, around a theme of their choice, composed largely of paintings drawn from the Louvre's archives. Derrida's choice focused on portraits or drawings representing the blind. 'And what about the day,' Jaques Derrida asks, 'the rhythm of the days and nights without the day or light, the dates and calendars that scan memories and memoirs of the blind be written?' Derrida wonders how there can be a journal of the blind, a daily accounting when to be blind is to live in darkness, never to see the sun, that clock by which we measure the day. How, in other words, can a blind man keep time? It is important to understand that when Derrida writes of the blind man, he is not necessarily talking about who have lost their sight to disease or injury, but rather about a double-figure: the philosopher and the artist. Thought begins, in Western metaphysics, where one draws a line, a conceptual boundary, such as that between day and night, without which there would be no categories, no taxonomy, no epistemology, no time. However, the drawing of that line, the making of representation, is an act of the blind. To draw a portrait, the portraitist must turn away from the sitter's face and see the lines or traits on his paper. Similarly to write the word 'face', one must turn away from the real and attend to the lines that form the word. In both instances, this turning away—from the face to the portrait, from thing to its name—this trope, is the fundamental concern of both art philosophy (Derrida 1993a). Douglas problematises the representation of the real by painting the blind poet among the butterflies. The metaphorical blindness of poet is assisted by the imaginations of the words. He highlights that the word is to be engraved similar to the lines he draws, but the world of tenderness and beauty embodied in the butterflies is both elusive and imaginary. In the paintings I and II (Figures 13 and 14) he creates multiple panels that progress from right to the left. In the painting I (Figure 13), the progression shows the butterfly travelling from pure nature to captivity in a box to be examined by the blind poet. In the painting II (Figure 14) the poet himself is embodied in words. In Li Po's poem, there is a line, 'Did Chuang Chou dream he was a butterfly or the butterfly that it was Chuang Chou? In one body's metamorphoses, all is present, infinite virtue.' In the ninth painting in the series (Figure 15) we see the worlds of words and lines and the universes of poets and butterflies merge in one plane. Perhaps, in this painting Douglas reveals his spiritual quest for a world unmediated by lines and words.

Figure 15: 'Blind Poet & the Butterflies - IX'; 53 x 41 inches; mixed media on paper mounted on canvas 2011

Figure 16: 'Blind Poet & the Butterflies - X'; 53 x 41 inches; mixed media on paper mounted on canvas; 2011

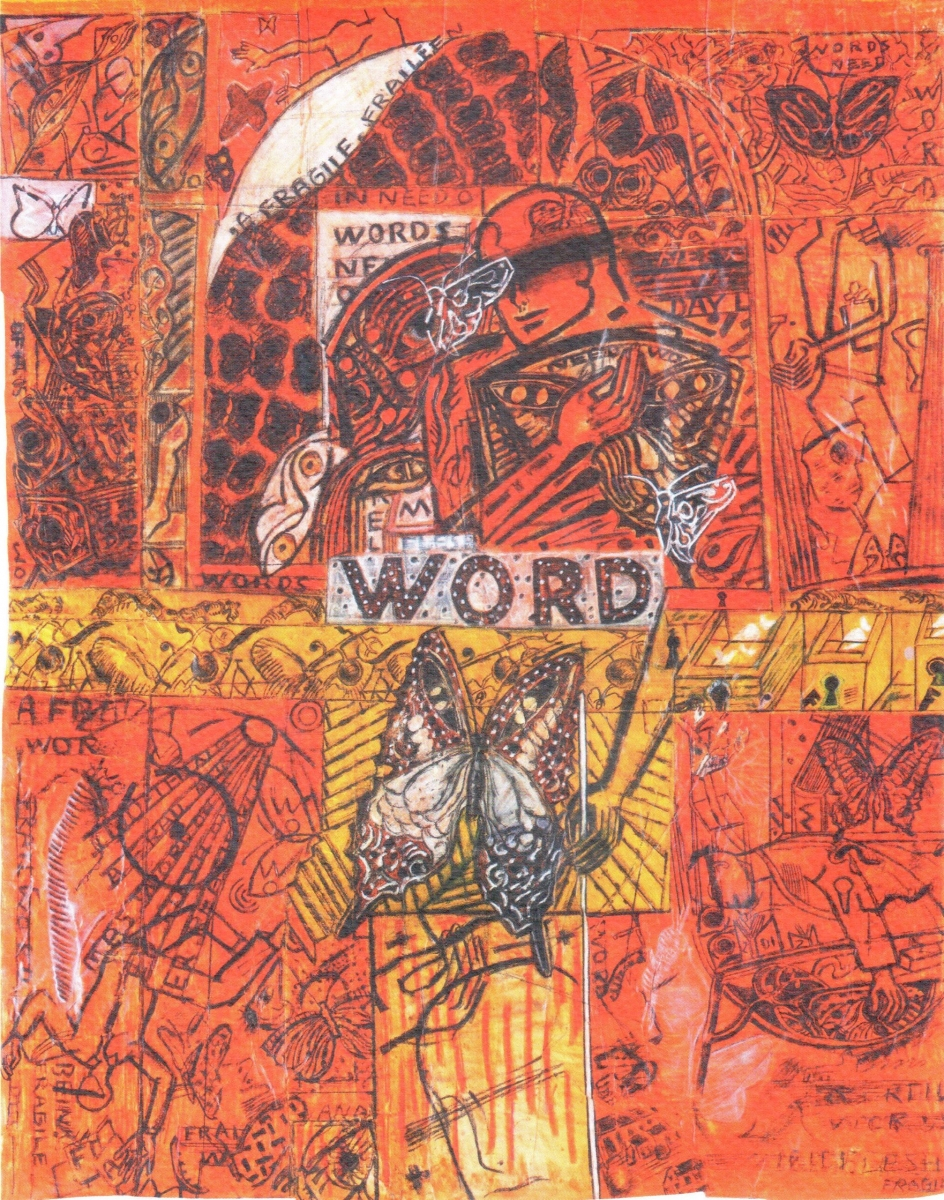

Like Douglas who is a voracious reader of contemporary philosophy and poetry, the blind poet easily traverses between the worlds of words, paint, everyday experience and memory as if they were seamlessly sewn together. In a way, the tenth painting (Figure 16) in the series Blind Poet & the Butterflies represents Douglas’ seamless world, and it has the written word literally at the centre of the painting with the letter O staring at you like an eye.

The series Blind Poet & the Butterflies is also Douglas' tribute to his mentor K.C.S Paniker's series Words and Symbols (1964). The line is almost everything in Paniker's later work, Joseph James argues, '(he) proceeded to test his drawings by denying it the convenience of the image. If one is to rely on images, as one conventionally does, for making the lines of one's drawing cohere, drawing becomes something to which an otherwise known thing can be reduced. Paniker in his Words and Symbols pictures reversed this role and attempted with his drawing to bring into being unknown bodies and substances. ...The extraordinary relationship between drawing and body that Paniker establishes is, of course, purely pictorial' (James 2004c:390–91). By cohering the word, line and the human body, Douglas invents a new relationship between the things that exist only in the sphere of art.

Has not Derrida written, 'What guides the graphic point, the quill, pencil, or scalpel is the respectful observance of a commandment, the acknowledgement before the knowledge, the gratitude of receiving before seeing, the blessing before the knowing'? (Derrida 1993b:29).

Figure 17: 'Twilight' (three panels of a single painting); 5.5 feet x 10.5 feet; acrylic on canvas; 2015

Twilight (Figure 17) is undoubtedly a modernist masterpiece with Douglas’ mellowed expressions. At the centre of the painting is an angry and grim fish swimming towards a hook hung by unknown hands. A man with his fishing net, weapons and a dog walks towards nowhere. Toy birds with their visible mechanical keys populate the branches. A wild net imprisons structures, houses, and people. An imposing lighthouse emits dangerous rays to reveal people caught in their nets. Twilight’s apocalyptic message is clear in Douglas’ grey, black, and muddy colours.

References

Barthes, Roland. 1978. A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments. 1st American ed. New York: Hill and Wang.

Baudrillard, Jean. 1994. Simulacra and Simulation. The Body in Theory. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Derrida, Jacques. 1993. Memoirs of the Blind: The Self-Portrait and Other Ruins. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

———. 1997 Of Grammatology, trans. Gayatri Spivak. Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press.

James, Josef, (ed.). 2004. Cholamandal: An Artists’ Village. Chennai: Oxford University Press.

Pessoa, Fernando. 2003. The Book of Disquiet, trans. Richard Zenith. Penguin Classics. New York: Penguin Books.

Rajagopalan, Ashvin. 2008. C. Douglas The Mind of an Artist. First. Madras: Ashvita Art Objects & Artifacts.

T︠svetaeva, Marina. 2009. Bride of Ice: New Selected Poems, trans. Elaine Feinstein. Rev., enlarged 6th ed. Manchester: Carcanet.